by Karen Uhlenbeck

Karen Uhlenbeck is an avid lover of nature, a mathematician, and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the National Academy of Sciences. Her interest in math arose, in part, from her preference to work alone, her natural bent for abstraction, her love of ideas, and her lack of success in undergraduate physics. Although she faced blatant sexism early in her career, she never took it personally, realizing that prejudice treats an individual as a member of a class or group instead of as a person.

My first love is the outdoors — I enjoy mountain climbing, back packing, hiking, canoeing, swimming, and bicycling. Many of these interests I inherited from my parents who, at age 83, are still hiking and back packing. I am at home in nature and, when I can't be out in the wilderness, I can often be found in my garden at my home in Austin. That's the real me. My day-to-day life is something very different.

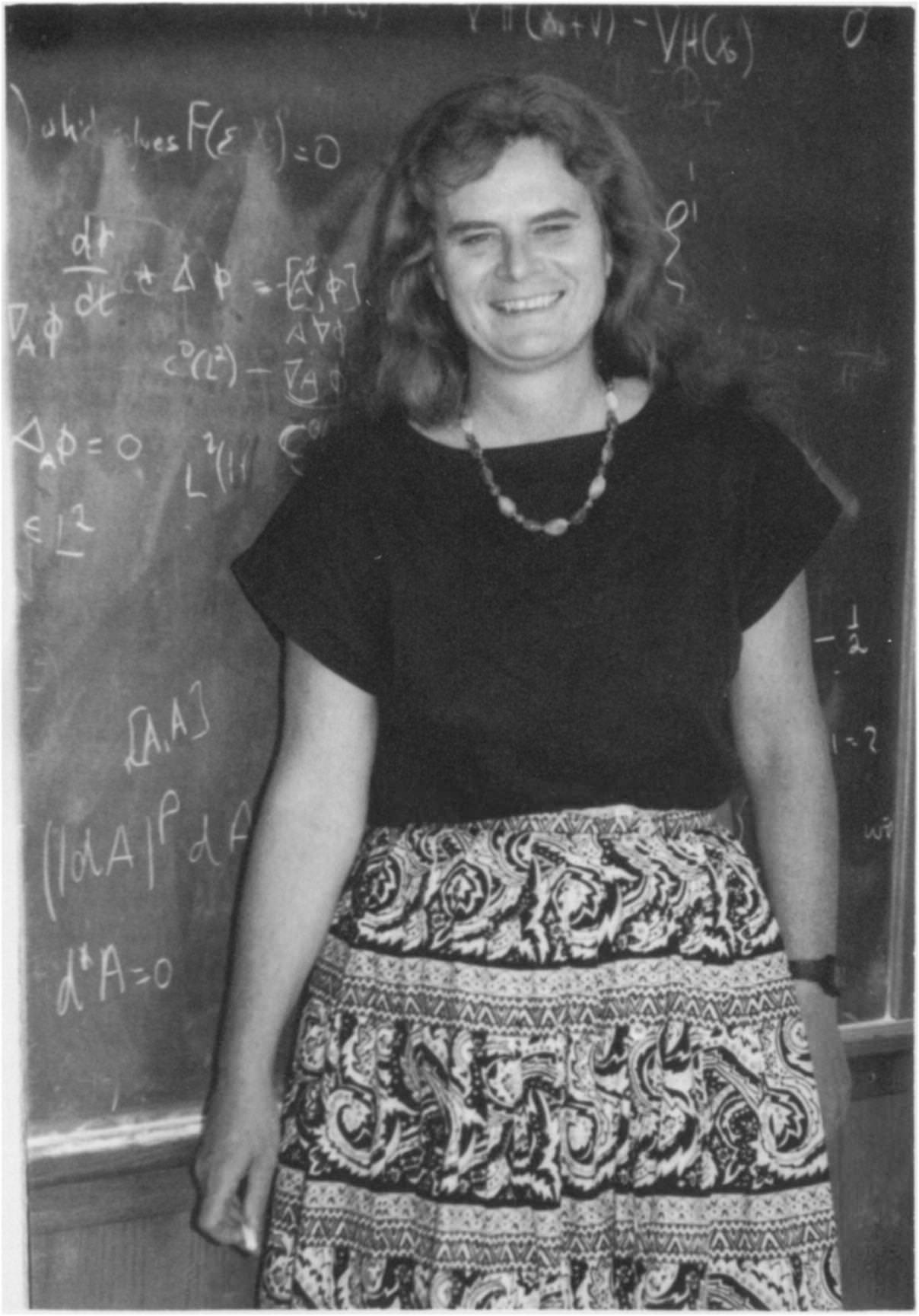

I am a mathematician. Mathematicians do exotic research so it’s hard to describe exactly what I do in lay terms. I work on partial differential equations which were originally derived from the need to describe things like electromagnetism, but have undergone a century of change in which they are used in a much more technical fashion to look at even the shapes of space.

Mathematicians look at imaginary spaces constructed by scientists examining other problems. I started out my mathematics career by working on Palais’ modern formulation of a very useful classical theory, the calculus of variations. I decided Einstein’s general relativity was too hard, but managed to learn a lot about geometry of space time. I did some very technical work in partial differential equations, made an unsuccessful pass at shock waves, worked in scale invariant variational problems, made a poor stab at three manifold topology, learned gauge field theory and then some about applications to four manifolds, and have recently been working in equations with algebraic infinite symmetries. I find that I am bored with anything I understand. My excuse is that I am too poor an expositor to want to spend time on formal matters.

As a young academic I worked by myself a lot. In fact, that was one of the attractions of mathematics. I am the eldest of four children and I consider dealing with my siblings the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life. That had a great impact on my choosing a career — I wanted a career where I didn’t have to work with other people. I’ve always been competitive, but I find it difficult to cope with the attitudes of people who lose. It is still attractive to work in an area where I compete only with myself and don’t have to deal with the negative aspects of competition. As my career advanced, however, I found I had a lot to learn from other people of all sorts. I have found it very rewarding to deal with younger mathematicians, and I now truly enjoy collaborative projects.

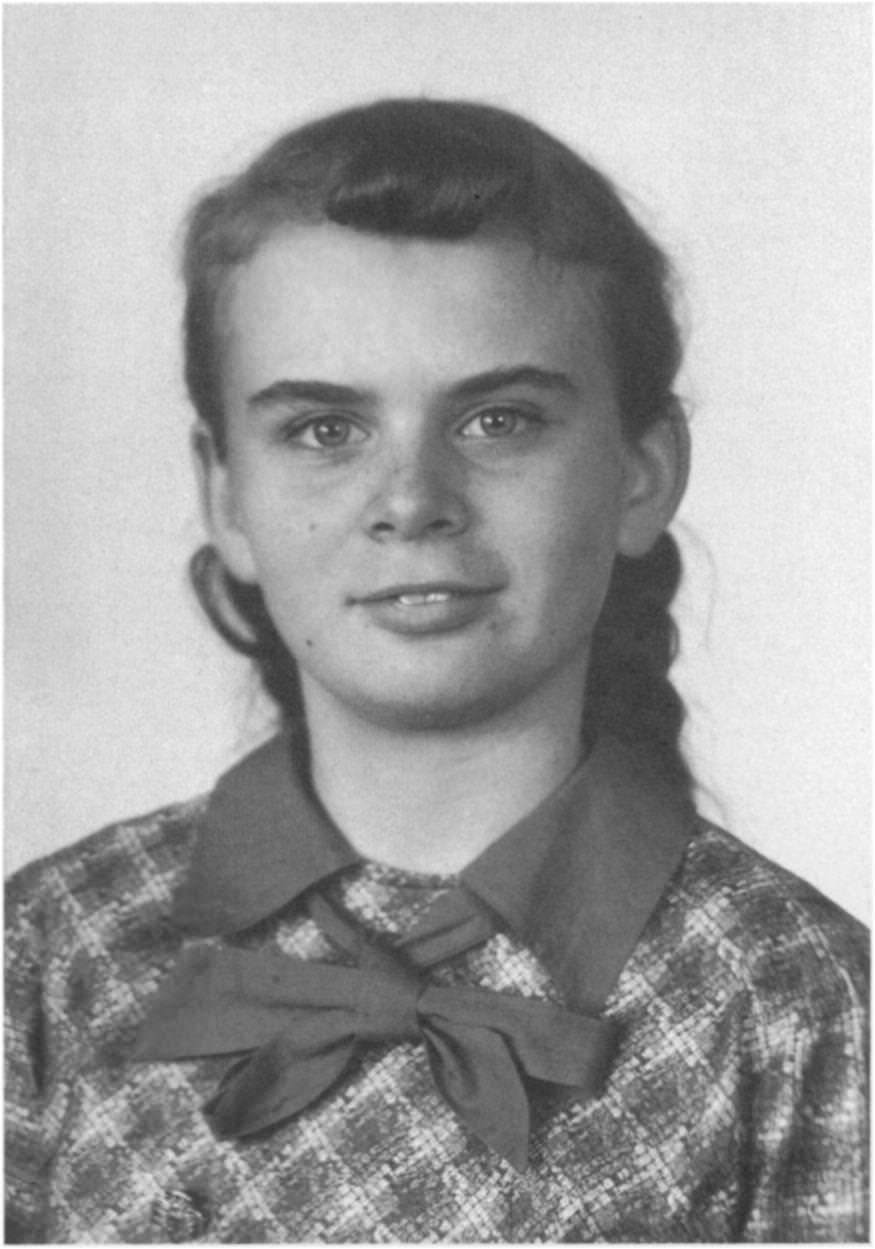

I can’t say that I was really interested in mathematics as a child or adolescent, mostly because one doesn’t really understand what mathematics is until at least halfway through college. As a child I read a lot. I read everything, including all the books in our house three times over. I’d go to the library and then stay up all night reading. I used to read under the desk in school. My whole family were and still are avid readers; we lived in the country so there wasn’t a whole lot else to do. I was particularly interested in reading about science. I was about twelve years old when my father began bringing home Fred Hoyle’s books on astrophysics. I found them very inspiring. I also remember a little paperback book called One, Two, Three, Infinity by George Gamow, and I remember the excitement of understanding this very sophisticated argument that there were two different kinds of infinities. I read all of the books on science in the local library and was frustrated when there was nothing left to read.

I grew up in New Jersey and, since there wasn’t a state university at the time, I went to the University of Michigan. Since both of my parents were the first generation of people in their families to go to college — my father was an engineer, my mother an artist — there was never a question that I would go to college. I wanted to go to MIT or Cornell, but my parents decided that those institutions were too expensive and the University of Michigan was affordable. I was lucky enough to get into the honors program at Michigan. I had very advanced courses as a freshman and received a superb education. I had a junior-level math course which I found very exciting. I had intended to major in physics and decided to change majors when they started taking attendance in the physics lecture. I also had trouble with labs — I could not learn to look up answers in the back of the book and fudge the experiments. I could never seem to get the labs to come out right. So I switched to math and have been interested in it ever since.

There are three women Ph.D. mathematicians from my freshman honors class at Michigan. Some people at the University of Michigan have a theory to explain this phenomenon of success rates of women from their honors program during this time period: bright women were not sent to expensive, private colleges, so they came to places like Michigan with honors programs. If we had been bright men, they suggest, our fathers would have forked out the money to send us to Ivy League schools.

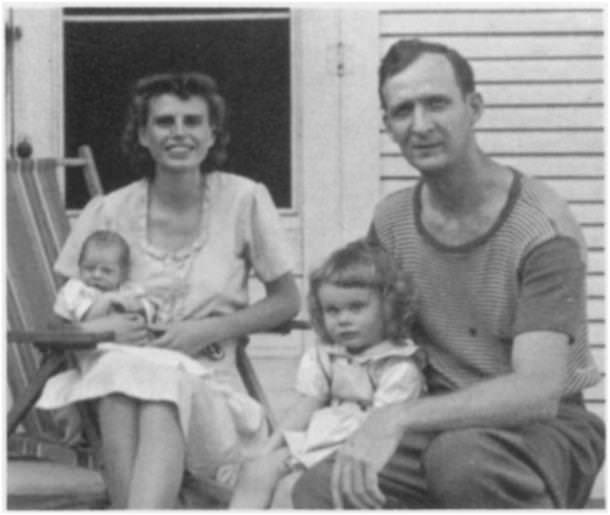

After undergraduate school I spent a year at New York University’s Courant Institute (1964), but then married a biochemist who was going to Harvard, so I switched to Brandeis. I had a National Science Foundation graduate fellowship at that time, so four years of my graduate school were paid for at a very luxurious rate. I was one of the people who benefited from Sputnik. There was a handful of women in my graduate program, although I was not close friends with any of them. It was evident that you wouldn’t get ahead in mathematics if you hung around with women. We were told that we couldn’t do math because we were women. If anything, there was a tendency to not be friendly with other women. There was blatant, overt discouragement, but also subtle encouragement. A lot of people appreciated good students, male or female, and I was a very good student. I liked doing what I wasn’t supposed to do, it was a sort of legitimate rebellion. There were no expectations because we were women, so anything we did well was considered successful.

I have always known that I was a really good mathematician. I have a natural bent for abstraction and I love ideas of all sorts. I value time to be by myself and think, about math or other things, it doesn’t matter. The noise of the world is a difficult thing for me to deal with. I have always had a hard time handling external stimuli.

My first husband’s parents were older European intellectuals and my father-in-law was a famous physicist. They were very influential in my life. They had a different attitude toward life than Americans. I remember my mother-in-law reading Proust and giving me her English version when she learned to read it in French. My in-laws valued intellectual things in a way that my parents didn’t; my parents did value such things, but they believed that making money was more important. I don’t think I would have survived at that stage of my career without the encouragement from my first husband’s family.

After graduate school I had two temporary jobs. I taught for a year at MIT while my husband was finishing his Ph.D. in biophysics at Harvard, and then I went for two years to the University of Berkeley during the Vietnam War. I was not the only woman in those respective departments, and I must say that all of these women (my contemporaries) succeeded spectacularly, probably because they had made up their minds to do what they chose.

I’m still processing a lot of what happened during those years. I think that some of the origin of older women’s lack of sympathy with feminists resulted from the fact that many of us were going along fine in our careers, and then somebody started shouting that you were nobody and you weren’t supposed to be there. But there you were, and suddenly there was all this fuss about women. Now they had to hire women. It bewildered many of us. It’s nice to know that maybe some of the roadblocks have been removed, but I bet that what actually happened was not very useful to anybody.

I was told, when looking for jobs after my year at MIT and two years at Berkeley, that people didn’t hire women, that women were supposed to go home and have babies. So the places interested in my husband — MIT, Stanford, and Princeton — were not interested in hiring me. I remember being told that there were nepotism rules and that they couldn’t hire me for this reason. When I challenged them on this issue years later, they didn’t remember saying these things and, interestingly enough, there were no nepotism rules “on the books.” I would have rather they’d been honest and said they wouldn’t hire me because I was a woman. I want to be valued for my work as a mathematician, not because I’m a member of a particular group.

At that point in time people were saying all kinds of things about women, most of which had nothing to do with me personally. Prejudice is very rude because it treats you as a member of a class or group instead of as a person. People were tremendously rude.

I ended up at the University of Illinois, because they hired me and my husband. In retrospect I realize how remarkably generous he was because he could have been at MIT, Stanford, or Princeton. I hated Champaign-Urbana — I felt out of place mathematically and socially, and it was ugly, bourgeois and flat. I was lucky to receive a Sloan Fellowship and, instead of doing something mathematically useful, I took time off from teaching to rearrange my life. I had already met Lesley Sibner, who has served me since as role model and advisor many years. I also started to work Jonathan Sacks and was taught Teichmueller theory by Bill Abikoff. These were my first close mathematical contacts. I moved to Chicago, established what has proven to be a long-term relationship with Bob Williams (a somewhat older mathematician), taught temporarily at Northwestern and then permanently at the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle. I also became friends with S. T. Yau, whom I credit with generously establishing me finally and definitively as a mathematician.

I moved from Chicago Circle, with some regrets, to the University of Chicago in 1982, the same year I received a MacArthur Fellowship. It has been a struggle for me to come to grips with my own success. By looking around me at the fate of other women who wanted to be mathematicians, I can intellectually, if not emotionally, understand that this is not so surprising. Not that the fate of other women is surprising, but I really don’t understand my success.

I think what has changed today is that people are tremendously more subtle, so that you don’t know what you’re up against. This is true not only for women but for a lot of young people. Young people today are up against the fact that most of the young scientists are coming from abroad, and so most of the people coming into academia are being trained somewhere other than the United States. No one ever talks about this phenomenon of who is actually succeeding in the sciences and engineering — foreign-born men and women. I try to talk about this with my students. It’s difficult, however, because you’re not supposed to talk about it. In the large classes of engineering students I teach, I’m see a lot more diversity — women, Hispanics, African-Americans. It can be done, not just by white, Anglo men.

I am currently at the University of Texas in Austin, and there are three women in the math department, two full professors and one associate professor. I run a mentoring program for women in mathematics which is two years old. I am aware of the fact that I am a role model for young women in mathematics, and that’s partly what I’m here for. It’s hard to be a role model, however, because what you really need to do is show students how imperfect people can be and still succeed. Everyone knows that if people are smart, funny, pretty or well-dressed they will are succeed. But it’s also possible to succeed with all of your imperfections. It took me a long time to realize this in my own life. In this respect, being a role model is a very un-glamorous position, showing people all your bad sides. I may be a wonderful mathematician and famous because of it, but I’m also very human.