by Allyn Jackson

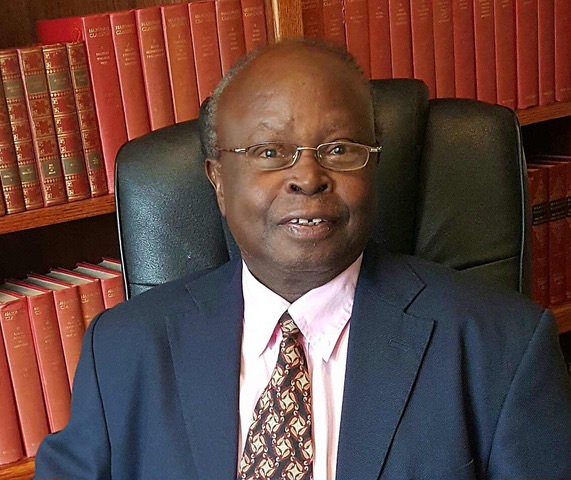

Born in 1947, Augustin Banyaga is the first Rwandan to earn a PhD in mathematics. He had a happy childhood growing up on his family’s banana plantation not far from the Rwandan capital, Kigali. In secondary school, he stood out as the top student. He obtained a scholarship to study mining engineering at the University of Geneva but soon switched to mathematics — and there too became the top student. Under the guidance of André Haefliger, Banyaga earned three degrees from Geneva: Licence ès Sciences Mathématiques (1971), Diplôme de Mathématicien (1972), and Docteur ès Sciences Mathématiques (1976). With Haefliger as a magnet for research in geometry and topology, Banyaga found in Geneva the opportunity to meet many of the outstanding mathematicians of the day.

After it became clear he could not obtain a position in Rwanda, Banyaga spent a year (1977–1978) as a postdoc at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton and then four years at Harvard University as a Benjamin Peirce Instructor. He taught at Boston University until 1984, when he joined the faculty of Pennsylvania State University. Today he is a professor of mathematics and distinguished senior scholar at Penn State. He became a United States citizen in 1995.

Banyaga is a leading figure in geometry and topology, having made important contributions in symplectic and contact geometry/topology and in Morse theory. He has also devoted a great deal of energy to developing mathematical talent in Africa, where his stature in research, together with his joyful enthusiasm for mathematics, have had a major influence. He is on the scientific committee for the Institut de Mathématiques et Sciences Physiques in Benin and has served on the selection committees for the African Mathematics Millennium Science Initiative and the Simons Foundation’s Africa Mathematics Project. He serves on the editorial boards of Afrika Matematika and the African Diaspora Journal of Mathematics. He was elected a Fellow of the African Academy of Sciences in 2009.

What follows is an edited version of an interview with Augustin Banyaga, conducted in December 2019.

Chasing pigs on the plantation

Jackson: Can you tell me about your parents?

Banyaga: They were born in Rwanda, in a village called Gasabo, near the capital Kigali. The village in which I was born is also near Kigali — it’s called Gisozi.

Jackson: Did they also come from farming families?

Banyaga: Everybody was a farmer. In Rwanda at that time, there were very few jobs. My dad learned masonry. Of course he didn’t go to school. There was almost no school at the time he was growing up.

Jackson: And your mother also did not go to school?

Banyaga: No.

Jackson: Did they learn to read?

Banyaga: No.

Jackson: You are Hutu, is that right?

Banyaga: Yes — how do you know?

Jackson: The Haefligers told me about you and your wife and said that one of you is Hutu and the other is Tutsi. You come from a farming background, and I read that the Hutus were farmers and the Tutsi were cattle ranchers. So I guessed that you are Hutu and your wife is Tutsi.

Banyaga: Yes, but my wife’s parents had no cattle at all! Her father was a carpenter. We are both from the same village. I knew her when she was very small — she is 6 years younger than me.

Jackson: Did your parents already have the banana plantation when you were born?

Banyaga: Yes, they were already on the plantation, in the village Gisozi. Each kid in our family was supposed to have a piece of the property and make his or her own plantation. So I had a few banana trees I planted myself.

Jackson: You had siblings?

Banyaga: Yes. We were 5 children. My two brothers are still in Rwanda, and my two sisters are with me in the US. They came as refugees.

Jackson: When did they come to the US?

Banyaga: About 20 years ago. After the civil war, they were refugees in Congo, and we managed to get them to the US.

Jackson: What was life like on the banana plantation?

Banyaga: It was really great. I loved it. In the morning I walked to school, and this was quite long, maybe a few miles. When I came back, I would go to my plantation. We kids used to play together. I had a couple of pigs, and we would run and chase them. It was fun.

Jackson: So you had a lot of freedom to play and be outdoors.

Banyaga: Absolutely.

Jackson: Did your family have meals together every day?

Banyaga: Yes. There was no shortage of any kind. Mainly we ate sweet potatoes, beans, cassava, and a bit of goat meat.

Jackson: Were your parents very strict?

Banyaga: No. Actually, all the kids were so nice, the parents did not have too much to do. We were very correct. But if somebody did something stupid, the parents would punish them a little bit.

Jackson: Where were the bananas sold?

Banyaga: The bananas we grew were sold in the local market. But we also used them to eat them and to make banana wine.

Jackson: Does the wine taste like bananas?

Banyaga: No. It tastes almost like white wine. When I was a student in Geneva, I used to tell my friends that they were drinking Swiss wine, but I had given them banana wine! It’s not very different from Swiss wine.

Jackson: Did you make the wine yourself?

Banyaga: No, but I knew how to extract the juice. You first let the bananas ferment. They become yellow and soft. Then you remove the skin and macerate them using some herbs. Little by little, the juice comes out. It’s not easy.

Jackson: What was your primary school like?

Banyaga: It was very nice. Half of the school was given in French, so we had to learn a lot of French in the beginning. We used books from Belgium, because we Rwandans didn’t have any books at all — or, we didn’t produce our books. The math books would have problems where a train would leave Brussels at this time and arrive in Luxembourg at that time; how many hours did you spend on the train? This was the kind of problem we were doing.

Jackson: I read that there were no train lines in Rwanda.

Banyaga: No, there weren’t! They just translated the European situation to Rwanda. Some kids got lost because of that. But if you have some imagination, you can think about it and abstract it.

Jackson: Where were the teachers from?

Banyaga: They were Rwandans who had studied in the school for teachers. Sometimes we had white priests as teachers, but that was mostly in the secondary school, not in the primary school.

Jackson: You had to learn French and mathematics. What other subjects did you study?

Banyaga: Religion — religion was very important. Also history and geography.

Jackson: The religion that you studied was Catholic religion?

Banyaga: Yes.

Jackson: Were you raised as a Catholic?

Banyaga: Yes. My mom used to go to the mass very often.

Jackson: And your father?

Banyaga: Less! But he went too.

“The people who poison others”

Jackson: What language did you speak at home — the Rwandan language?

Banyaga: Yes. Rwanda is one of the very rare countries in Africa that has a unique language for the whole country — just Rwanda, Burundi, and a few other countries. Kinyarwandan is a very pleasant language. When I was a kid, I liked to read and to write. Actually, I published a book in Rwandan language when I was 18. It was a short novel.

Jackson: What was it about?

Banyaga: The title was Muringuriza, which means “the people who poison other people.” There were legends around in the country that, each time somebody dies, it’s not by a natural cause, but because somebody poisoned the person. Even somebody who doesn’t know you, who doesn’t even hate you, might poison you, according to the legend. The novel is about people who poison other people for no reason at all.

Jackson: This sounds scary and grim.

Banyaga: Yes. But the goal of my book was to tell people how this is stupid. For instance, when my mother died, people said she had been poisoned by our neighbor. I didn’t believe it. She went into the hospital, so I asked the doctor about her, and the doctor told me she had had cancer. So I didn’t believe the legend. But everybody else believed it.

People believed that the people who poison did it randomly to anybody, with no reason. This is why I thought it was completely absurd.

Jackson: Did your siblings believe she had been poisoned?

Banyaga: Yes.

Jackson: And your father also?

Banyaga: Yes. Everybody believed it.

Jackson: How old were you when she died?

Banyaga: Maybe about 15 years old.

Jackson: That’s very sad. But at 15, you understood this was a superstition, even though everyone around you believed she’d been poisoned. You were different. What did your family think of your novel?

Banyaga: They liked it, but if you believe the legend completely, you are not going to believe what I am saying in the novel.

Jackson: So they liked the novel, but it didn’t change their minds.

Banyaga: No, it didn’t.

Jackson: How did you manage to get a novel published when you were only 18 years old?

Banyaga: There were periodical journals that were eager to publish interesting things. They published one chapter each week.

Jackson: So you just sent a chapter to one of the journals, and they agreed to publish it?

Banyaga: Yes.

Jackson: Your family believed the superstition when your mother died. But you listened to the doctor. Why were you different?

Banyaga: I can’t tell you. I don’t know! I was different. And I am still different!

Jackson: You’re skeptical, because you are a mathematician! Do you still have a copy of this novel?

Banyaga: Unfortunately everything disappeared during the civil war in Rwanda. I had it in my house there, and my house was vandalized. I had also brought some nice math books there. Everything was lost.

The seminary as educational opportunity

Jackson: Being a skeptical-minded kid, what did you think of the church and Catholicism when you were growing up?

Banyaga: Actually, after primary school, I went into a seminary to become a priest. Of course, I didn’t become a priest! But this is how I went to a seminary and how I studied Latin and Greek.

Jackson: Did you decide to go to the seminary because you wanted to get an education?

Banyaga: Exactly — this was the one opportunity I had. I am Hutu, and there were not many schools that were open to Hutus at that time, maybe just the seminary. The good, big, nice school was only for Tutsis. I studied at the seminary for three years. Then I went to another school that was not a seminary, it was an ordinary high school in Kigali. There the emphasis was science and Latin.

Jackson: Did your siblings also go on to secondary school?

Banyaga: No. It was very hard to enter the secondary school at that time.

Jackson: When you studied at the seminary, did you live there also?

Banyaga: Yes.

Jackson: Was that hard for you, to be away from the plantation?

Banyaga: No, it was a good change. Actually the school was also in a rural area, so you didn’t see too much difference when you looked outside.

Jackson: How did it come about that you switched to the secondary school in Kigali?

Banyaga: At some point I decided I did not want to be a priest anymore. I had seen that there were problems between white priests and black Rwandan priests. There were conflicts, and they were shouting at each other. I didn’t find this very Christian, to fight among themselves. I told our boss, the bishop, that the priests don’t live a good image of Christianity, because they hate each other. I didn’t want to be a part of this system. It was ridiculous. So I left.

Jackson: What was the conflict about?

Banyaga: Basically it was about racism. The priests from Belgium didn’t think that the Rwandans were good enough to be priests. And the Rwandans thought that the priests were sent by the colonizers to help colonization.

Jackson: The Rwandans felt that the priests were not there only for religious reasons, but to help the colonizers.

Banyaga: Exactly.

Jackson: When you told the bishop about the conflict between black and white priests, what did he say?

Banyaga: He was unhappy. He was a very good guy and helped me to find the other school. Actually, he was Swiss.

Jackson: But the bishop could not help to resolve the conflict between the black and white priests.

Banyaga: No, it was too big.

Jackson: Did you have any especially good teachers, at the seminary or later at the school in Kigali?

Banyaga: I don’t remember them, but I think they were okay.

Jackson: And the mathematics instruction in these schools?

Banyaga: That was okay too, but I have no special recollections.

Jackson: Are there experiences that you had as a young person that you now with hindsight see were inspirational in a mathematical sense?

Banyaga: I really loved symmetries. This is why I collected stones, quartz, flowers, etc. I think this was very important and stayed in my mind for a long time. Actually, this is geometry. Geometry is nature, the symmetry in nature.

Going to Switzerland by mistake

Jackson: At your school in Kigali, you graduated number one in your class, in 1966. Having been first in your class enabled you to get a scholarship to go to Switzerland, is that right?

Banyaga: I didn’t get the scholarship immediately, because again there was this Hutu/Tutsi stuff behind the scenes. If you were Hutu, you had fewer opportunities. There was another problem too, the problem of regionalism — if you are not from a certain region, you had fewer opportunities.

Jackson: You are a Hutu, so that reduced your chances, but you were from the “wrong” region also?

Banyaga: Yes! Somehow, I have been a victim all my life, because of inequalities about what you are, where you are from, who you are. And now I am a black in America! I managed always to be in the “wrong” group! But it’s okay. Actually, I have been lucky.

You know, I went to Switzerland by mistake.

Jackson: Really?

Banyaga: I was offered a scholarship to study mining in Belgium. The Swiss consulate offered me a scholarship, with more money, to study mining in Switzerland. They told me that Switzerland is a beautiful country, which is true, and that they have an excellent school of mining in Geneva, which is wrong! But I believed it. The general belief was that the Belgians had better schools for mining. So I went to Switzerland and started in the mining school.

I studied mathematics, physics, and geology. The good thing is that my linear algebra course was with André Haefliger, and I started connecting with math more than with geology. So the mistake of going to Switzerland became a very nice thing!

Jackson: When you took for example Haefliger’s linear algebra class, did you find the background you had from school in Rwanda was sufficient?

Banyaga: Yes. Actually, I progressed very quickly and even became the best in the class in Geneva.

Jackson: You decided not to continue in engineering studies, but could you still keep the scholarship?

Banyaga: They gave me one year to decide. If I decided to quit mining engineering, then they would cut off the scholarship. But at the same time, the math department saw that I was progressing well, and it soon offered me an assistantship.

Jackson: Was it a big culture shock for you to go to Switzerland?

Banyaga: Not really.

Jackson: Was it the first time you had been out of Rwanda?

Banyaga: Yes. But people were so nice. I never felt lost in Geneva. When I first arrived in Switzerland, I didn’t go directly to Geneva; I went to Fribourg. A lady there came to greet and to help the group of scholarship students. I still remember her. She is very old now. The last time we visited Switzerland, we met her again. She is wonderful.

Jackson: A person like that makes it easier to adjust to the new country, new hemisphere — new everything! Did the Swiss weather and the cold bother you much?

Banyaga: No. Sometimes I went to places in the mountains where people skied. The cold didn’t bother me.

Jackson: You have called your linear algebra course with Haefliger a turning point in your life. Can you tell me about that?

Banyaga: I learned later that Haefliger was actually one of the greatest mathematicians in the world. But of course I couldn’t have known that! I just saw a guy who was smiling, who was caring and nice, and who spoke extremely simply. He didn’t go too fast. He was devoted to making sure that we students understood the small details. Afterward, I took other classes from other people. I was super lucky to have a class with Georges de Rham. I tell my students now that I had de Rham as my teacher, and they say, “Wow!”

There is a joke de Rham told us. He said that what is important for mathematicians is the definitions. “I define old as any person older than me,” he said. “Theorem: I will never be old! Because I will never be older than myself!” This was a class in analysis — a long time ago.

Jackson: He was Haefliger’s teacher also, in Lausanne.

Banyaga: Yes. Geneva had a lot of nice people. Another was Michel Kervaire. Actually, all the important mathematicians I encountered later, I had already met in Geneva. They used to come to visit Haefliger — [William] Thurston, [John] Mather, [Raoul] Bott, even Jim Simons, who is now very rich and started a foundation. All the people I got to know later in Princeton, I had met in Geneva, except probably [John] Milnor. And Dusa McDuff I met in Coventry, England.

Jackson: Around this time you married your wife Judith. Did you get married in Geneva?

Banyaga: No, in Rwanda. On a trip from Geneva back to Rwanda in the early 1970s, I met her again, and we were then both adults. I went to Rwanda again in 1973, and at that time, the country was going through some political troubles. Tutsis were being beaten and sometimes killed. I wanted to rescue Judith, to save her. So I went there for about two weeks and we got married, and then I took her back to Geneva with me.

Jackson: There was a military coup in Rwanda in 1973.

Banyaga: Yes, that was a few months after I left Rwanda with Judith.

Jackson: Your timing was good! What was the situation of her family, and what happened to them in the coup?

Banyaga: They were okay. Her father was working as a carpenter in the military. The mother, like most the mothers, stayed home and took care of the children.

Jackson: Was it hard for Judith to go to Geneva?

Banyaga: I hope not! I had already an apartment, I had my life there.

Jackson: But to leave so quickly like that is hard. It wasn’t safe for her to stay in Rwanda?

Banyaga: It was completely unsafe to stay in Rwanda. As I said, a few months later, there was a coup by the military guys. The country was in a bad situation.

No one understood it: an unpublished paper by Thurston

Jackson: So this was 1973, and you had gone to Geneva in 1967, is that right?

Banyaga: Yes. I finished my bachelor’s degree in 1971, my master’s in 1972, and my PhD in 1976. I was pretty fast.

Jackson: Can you tell me about your PhD thesis work? Were you very much influenced by the work of Thurston?

Banyaga: Actually, his work was the motivation. Thurston had written a paper,1 and nobody would publish it, because nobody could understand it! Haefliger, after he visited Princeton, came to me and said, “Augustin, there is this paper that nobody has understood. Try to understand it, and try to do something with it.” Actually, I understood it, which is unbelievable. And I improved on it. I created a theory in which the result of Thurston would be a small part. This is related to the work of Mather too.

Jackson: How is it that you managed to understand Thurston’s paper that nobody else understood? Did you talk to Thurston about it?

Banyaga: No. I just stayed in my room for hours and hours and hours, for weeks and weeks. And finally some light came.

Jackson: Did you suddenly have a flash of insight?

Banyaga: Yes. I think this is the way things happen. You work a long time without anything, and very suddenly, something comes. Actually, that work opened all the doors for me, so that I was able to get positions at the IAS in Princeton and at Harvard.

Jackson: Was Thurston’s paper eventually published?

Banyaga: No. I don’t even have a copy anymore. My copy was probably destroyed in Rwanda. I don’t have the paper, but I know what’s inside!

Jackson: What was the subject of Thurston’s paper?

Banyaga: The subject was to study transformations that preserve a certain structure. The structure that interested me was more refined, more difficult than the structure of Thurston. This was related to Haefliger’s theory of foliations. I have actually spent most of my life studying these groups of transformations, and the book I wrote explained the main results.2

A few years after my thesis, I was able to prove a result on Klein’s Erlangen Program.3 Klein wanted to show that any geometry is completely characterized by its transformation groups. Now most of my mathematical work focuses on proving that symplectic geometry is characterized by its group of automorphisms. This is the biggest part of what I have done.

Jackson: Haefliger said that you also wrote a very good master’s thesis.4

Banyaga: This generalized ideas of another Swiss mathematician, Jürgen Moser, from ETH Zurich.5 It doesn’t happen very often that a master’s thesis is published.

Jackson: Can you tell me about this work?

Banyaga: If you have two volume elements on a manifold, there are diffeomorphisms that locally transform one into the other. Is there a global diffeomorphism that does this? Moser proved that, for a manifold without boundary, the answer is yes. What I did was to prove the same thing for a manifold with boundary. This is a completely different situation, because you have to study what goes on near the boundary.

Jackson: Where was your PhD thesis published?

Banyaga: In Commentarii Matematici Helvetici.6 This is a very important Swiss journal.

Jackson: While you were in Switzerland, did you travel around much in Europe?

Banyaga: Yes. I went to Montpellier and Paris, and many times to Marseille. Michèle Audin invited me to Strasbourg. I like her, she is wonderful. Michèle said that I am a member of the “Gang of Souriau.” Jean-Marie Souriau is one of the founders of symplectic geometry. He was in Marseille his whole life. Unfortunately he is dead now. I worked with one of his students, Paul Donato, for many years.

Jackson: When you finished your PhD, you tried to get a position at the University of Rwanda. But there was no possibility for you there?

Banyaga: The mathematics faculty of the University of Rwanda at that time were expatriates who had at most master’s degrees. They were afraid that if somebody who is more highly trained came around, it would be a danger for them. This is why they were not so thrilled with me coming there.

Jackson: But you wanted to go back?

Banyaga: Yes. But since the University of Rwanda did not want to hire me, I wrote to the Institute for Advanced Study and asked to visit. They immediately answered me, positively. And after that I went to Harvard University.

Home follows you

Jackson: I wanted to follow up on a couple of earlier questions. In school you were an outstanding student. What was the reaction of your family?

Banyaga: They were proud. Actually, my brothers learned professions; one is a carpenter, the other is a tailor. So they are successful. They have a good life in Rwanda.

Jackson: Did they have much trouble there during the civil war?

Banyaga: No, they kept quiet. That was not like me! I gave a television interview and said that I didn’t like that people were attacking the country. The people who were attacking are in power in the government now.

Jackson: What happened after this interview?

Banyaga: Nothing, but it means that I am not welcome to go to Rwanda now. And I don’t intend to go there anyway.

Jackson: Saying that a country should not be attacked sounds like a reasonable message. How was what you said perceived?

Banyaga: It depends. If you say you are against the attack, the people who supported the attack are against you. The people who are against the attack, they love you!

Jackson: You were the first Rwandan to get a PhD in mathematics. Is that why you were interviewed on TV? Are you well known in Rwanda?

Banyaga: Yes. I know personally some people who have been in the government. The present government is Tutsi and is from a group that came with an army from Uganda and took over Rwanda. The Rwandan genocide started at that time. The previous president [Juvénal Habyarimana], who died in a plane crash in 1994, had asked me to be prime minister. Of course I refused.

Jackson: Why did you refuse?

Banyaga: I told him that the country had almost completely disintegrated already. The aggression was so high, the people were very divided. Actually, if I had accepted, I would have been killed too.

Jackson: Why did he ask you? You’re not a politician. You are a mathematician!

Banyaga: Yes! I don’t know why. Maybe he thought that, if somebody is able to think correctly and do mathematics, that person can save the country.

Jackson: He knew you were smart and accomplished.

Banyaga: And I don’t have in my heart hatred of anybody. I don’t hate Tutsis, I don’t hate Hutus. So probably he thought I could make a good linkage between all the people.

Jackson: Were you tempted at all to take that position?

Banyaga: Not at all. I was writing beautiful papers. I was doing good mathematics.

Throughout my life, I have not been involved in politics. Now I am 72. When I left Rwanda, I was 20. You see, I spent almost all my life abroad. Usually I never talk about Hutu or Tutsi. But all these things are connected with my life somehow.

Jackson: They have followed you.

Banyaga: Exactly. I try not to be interested in what is going on in Rwanda, but I find myself looking at news from Rwanda every day! I can’t help it.

Jackson: I can understand that. You are interested in your home country even if in some sense you think it might be better not to be interested! When were you last in Rwanda?

Banyaga: After 1990, I didn’t go to Rwanda at all.

Jackson: Rwanda was colonized by Germans in the late 19th century and was part of German East Africa. Then it was transferred to Belgian administration after the first World War. Did German culture remain in Rwanda?

Banyaga: Not at all. Nobody spoke any German. The German presence was small and for a very short time. Generally, the colonization did not have too much influence on the regular people. There was really no contact with the colonizers.

Jackson: So you feel that a lot of the culture of the Rwandan people was preserved?

Banyaga: Yes.

Jackson: And the language also.

Banyaga: Yes. Actually the people who had a big influence are the Catholic priests. They are the ones who were going to villages, talking to people. They learned Kinyarwanda so they could talk to people.

Jackson: Where were your children born?

Banyaga: Two were born in Geneva, and one was born in Boston.

Jackson: The dedication in your book The Structure of Classical Diffeomorphism Groups lists your wife Judith and the names of your children. One of the names is RK.

Banyaga: RK is my son. His name is Rugigana Kavamahanga, which is too long! So we call him RK.

Jackson: You chose Rwandan names for your kids.

Banyaga: Yes. In the past in Rwanda, you didn’t necessarily take your parents’ name. For instance, my name is Banyaga, which by the way means “the conqueror.” My wife’s name is not Banyaga, it’s Mukaruziga. And each of our kids has a different name. There is no family name. This is a special tradition in Rwanda. But now it has changed, and in Rwanda if you marry a girl, she takes your name.

Jackson: Do you speak Rwandan language at home with your kids?

Banyaga: Yes. Unfortunately many Rwandans who stayed a long time abroad lost the habit of speaking Kinyarwandan. But we didn’t do that. We kept speaking Kinyarwandan.

Jackson: Have your kids been to visit in Rwanda?

Banyaga: Yes. I think 1989 was the last time we all went together.

The wonders of symplectic geometry

Jackson: In 1970, Haefliger gave some lectures about Mikhail Gromov’s PhD thesis, which Gromov had just finished in St. Petersburg. Did you meet Gromov in Geneva?

Banyaga: I didn’t see him in Geneva, but I saw him later many times. I remember Haefliger’s lectures. Everybody loved them. Maybe they were the reason Gromov could enter Europe.

Jackson: It was not long afterward that Gromov left the Soviet Union. Haefliger spread the word about his work.

Banyaga: Absolutely. Haefliger has been a big influence on many people in the mathematical world. And Gromov has had an influence on everybody! I just finished writing the proof of a theorem related to the Gromov–Eliashberg theorem. It is in a paper I wrote with a student and submitted last week.

Gromov is an eternal influence on geometry. He was the first to notice and use the fact that there is a connection between symplectic geometry, Riemannian geometry, and complex analysis. He invented the terminology “pseudoholomorphic curves” and wrote a fundamental paper about them. Pierre Pansu, a very good French mathematician, wrote a huge thesis just on that paper and has spent all his life studying this. The theory of pseudoholomorphic curves is at the center of everything now in symplectic geometry. Gromov also made up the term “soft and hard symplectic geometry” — “soft” meaning, everything that does not involve his new theory! And “hard” meaning, anything involving his theory!

Jackson: He doesn’t mean “hard” as “not easy,” and “soft” as “easy”?

Banyaga: Not really. It’s poetical terminology. Actually, soft can be harder than hard! And hard can be easier.

Jackson: What kind of mathematics do you like? What kinds of problems or ideas appeal to you?

Banyaga: I have been working in symplectic geometry. Grosso modo, symplectic geometry is something that is at the base of mathematical physics. It’s the basis of mechanics. What is nice about it is that, from there, it goes in all mathematical directions, even into applied math. I have been working also on the generalization of symplectic geometry. For the last ten years, I have been thinking about a new idea of trying to understand what happens if you don’t ask the structure to be differentiable. Differential geometry, by definition, is geometry in which you use analysis. Differential functions are nice to use, but in reality, you don’t see them much. Reality is less smooth and more continuous.

There is a trend now to treat the theme, “What is continuous symplectic geometry?” without using differentiability. The main idea is what is called now the rigidity of Gromov and Eliashberg. This was done by Gromov in 1986, 1987.

Jackson: What does rigidity refer to?

Banyaga: Rigidity means that you wonder what happens if you are allowed to deform things continuously. What doesn’t get killed when you push continuously? Properties that don’t get killed are called rigid. The big difference is between continuity and differentiability.

Jackson: You mentioned that symplectic geometry comes up in applied mathematics too. Apart from in physics, are there real-world applications of symplectic geometry?

Banyaga: Yes. I once directed a thesis7 on the application of symplectic geometry to radar and sonar, which are used in the military to detect flying objects. My student and I wrote a paper on radar and sonar.

Jackson: Was it published in a math journal?

Banyaga: Actually, it was written for the US Navy and was classified. But I think it’s declassified now — we could publish it if we want. My student hoped to get a job with the Navy after his thesis, but he didn’t get the job. Our theory covered the situation in which the radar works in an atmosphere that is not clean and clear, or works under water. Our theory would be more useful than the regular theory of radar. You know what they told us? They said, “The Cold War is over, so we don’t need it!” I told my student, you are the first casualty of peace!

Jackson: How did you come upon this problem of radar and sonar?

Banyaga: My student came to tell me about it, because he was already working for the Army. He asked me what we can do to improve radar. The question is related to group representations, and group representations is very close to symplectic geometry.

Jackson: What is the student doing now?

Banyaga: He works for a university in Thailand, in Bangkok. He is half American, half Thailandese.

Jackson: Is that the only time in your career when you worked on such an applied problem?

Banyaga: Yes.

Jackson: When you think about mathematics, what takes place in your mind? Do you visualize things? Can you characterize your thinking?

Banyaga: I think mathematicians, like all people, have a mission. My mission is to try to understand some intriguing things in the world. There is a guy who I like very much, Leonid Polterovich. He talks about the “wonders of symplectic geometry.” The Eliashberg–Gromov rigidity is one of them, and there are a couple of others. I have been fascinated by these wonders. My mission is to try to understand them.

When you think about mathematics, there is always a concept. You try to make it both real and abstract, at the same time. If your idea is just real and has no abstraction, you cannot make progress.

For instance, there is a notion I like called displacement. You have a subset, and you look at all the motions that displace the subset from itself. Now you look at the size of the transformation that moves it from itself. To do this, you have to put a norm on the transformations. One of the wonders of symplectic geometry is the norm that was invented by [Helmut] Hofer in 1990.8 The minimum of this norm is called the displacement energy.

Hofer’s norm is one of the famous results of the 20th century. I have worked on this and have been able to generalize the norm to bigger groups than the group on which he was working. This is the kind of object I have been studying for the last five or ten years.

Jackson: When you think of the displacement, are you visualizing something moving?

Banyaga: Exactly. Moving, distorting itself, and in the end it goes outside of the place in which it was before.

Jackson: You said you are trying to make things real and at the same time abstract. Displacing is very real.

Banyaga: And what is abstract is the notion of size, the size of the transformation. When you bring in this abstraction, you have a huge amount of material in mathematics that you can use.

Giving back to Africa

Jackson: After your PhD you wanted to return to Rwanda, but that did not work out. Later you started a PhD program there.

Banyaga: Yes, later I found a way with funding from UNESCO, which gave me the opportunity to visit Rwanda occasionally and start a program. This was in the 1980s.

Jackson: When you were already at Penn State?

Banyaga: No, it started earlier. I came to Penn State in 1984. The program started when I was at Harvard and Boston University and continued at the beginning of my time at Penn State. But after a while, the program just stopped. I don’t know why.

Jackson: By that time were there PhD mathematicians there who could take students in Rwanda?

Banyaga: No, there were no Rwandans and not even any foreigners.

Jackson: So you were the only possible advisor for a math PhD there.

Banyaga: Yes. I took a few people from Rwanda — one or two to Boston University, and another to Penn State. I was successful with one of them. He got his PhD in 1991 from Penn State with me.9 Since then, he has remained in the US and is at Florida International University.

Jackson: Did the PhD program in Rwanda die out because you could not spend so much time there?

Banyaga: That was one reason, and second, there were no students. There was no interest. Maybe it was premature.

Jackson: Why was there a lack of interest? Did people not understand what kind of careers mathematics might lead to?

Banyaga: Probably. Anyway, it didn’t work.

Jackson: You are not able to do anything to support mathematics in Rwanda, but you have done this in other countries in Africa.

Banyaga: Yes. I found another African country that I consider my country, Benin. I have gone there almost every year for almost 20 years. In my adult life, I know more of Benin than Rwanda. My adult life in Rwanda is zero. I was not there.

Jackson: What differences do you see between Benin and Rwanda?

Banyaga: The similarity is that they are both very small countries. The difference is that Benin is more open. The typical Beninois is like a French guy — a guy who shouts, who laughs. A typical Rwandese is just the opposite — quiet, doesn’t shout.

Jackson: What do you do when you go to Benin?

Banyaga: I give lectures, I talk to students, I do research, I collaborate to write papers. In 2017, I published a book containing a summary of lectures I have been giving in Benin for several years.10 The Benin guy who wrote it with me was my assistant. This is one of the jobs I have to do when I go to Africa — to take somebody and train him, to help him and work together with him.

Jackson: Have you gotten PhD students from Benin also?

Banyaga: Yes. I have several. One who wrote his thesis11 in 2012 is now at the University of Buea in Cameroon. I am proud of him. He is very good. He just wrote to me this morning; he is trying to help my current student in Benin.

Jackson: What do you see as the prospects for development of mathematics in Africa? What’s needed? What potential do you see?

Banyaga: Today there are more mathematicians outside Africa who are willing to go there, and there is more funding. For instance, the German Research Foundation [Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft] is funding several chairs in several universities in Africa. This is wonderful. Also, the institute in Benin12 now has a Center of Excellence funded by the World Bank. I am an advisor for this center. There are opportunities, there is more funding, and there are young people who are ready to work. The situation is much better than 20 years ago.

Jackson: In the US, there is a lot of concern about the need to encourage more underrepresented students in the so-called STEM [science, technology, engineering, and mathematics] fields. How does this issue look to you? Do you see improvement?

Banyaga: In general, I don’t see much improvement. For instance, in the particular case of Penn State, we have very good women mathematicians. But black mathematicians — for many years there was only me. In 2001, we hired a black mathematician from Senegal. Everybody said, “The black population in math at Penn State went up 100 percent!” Black American students, I don’t see any; Latino students, I don’t see much. We have a lot of Asian students, especially from China. But that is the trend everywhere.

Jackson: Math departments everywhere in the US struggle with this. The numbers of underrepresented students are so small, that even if the department wants to encourage them, they just don’t get the students.

Banyaga: Exactly. In contrast, African mathematicians go much more often to Europe, especially France and Germany.

But I think Africa itself has potential to develop. They have opened more good schools and more centers. They have help from Europe and the US. The Simons Foundation also has a program, called Math in Africa. I was on the committee for that. I am really optimistic. I think the situation should improve.

Jackson: There are also the AIMS centers.13

Banyaga: Yes. I have visited the AIMS in Senegal several times and directed several master’s degrees there. The students were very good. AIMS Senegal also has a Humboldt Fellowship that funds a chaired professorship. The chair now is an excellent Senegalese mathematician [Mouhamed Moustapha Fall]. And I just heard a colleague saying that the Humboldt Foundation is also funding a chair at the AIMS center in Rwanda.

Jackson: Yes, there is an AIMS in Rwanda now.

Banyaga: I think it’s the newest one.

Jackson: What is it like to be a black man in the United States today?

Banyaga: Personally, I don’t feel anything bad or any pressure. Actually, I feel better in the US than in France or Germany. Here, I am not a stranger. There are many black Americans.

In the small town in which I live, there are very few African-Americans. But there are no problems, no racism. Everybody looks after themselves, and nobody bothers anybody else. I feel much safer here than I would in Rwanda! There is no problem in day-to-day life.

Jackson: And when you look nationally, more broadly, what do you see?

Banyaga: Nationally I think the situation is getting better. Even with Trump! I think the First Step Act, which he signed into law, has helped make the incarceration laws that put a lot of blacks into jail more gentle.

Jackson: You have a very positive outlook.

Banyaga: Yes, absolutely. Next year, I have a sabbatical leave, I will go to Africa again. Everything looks positive.

Jackson: I wonder if your positive outlook comes from your childhood, running around the banana plantation.

Banyaga: Yes, it is connected.

Jackson: That sounds like it was a very happy time, very free; you had a lot around to interest you, growing your own banana trees and looking at nature.

Banyaga: Exactly. And I must say that I have been really lucky, to go to Switzerland by mistake, and find Haefliger, and find geometry, and meet so many mathematicians and do my work. I feel myself a lucky guy. Here at Penn State, I found someone I have been working with for more than 15 years, David Hurtubise. We wrote a book together.14

Jackson: It’s nice to have a collaborator at your own institution.

Banyaga: Yes, it’s great.

Jackson: I wanted to ask you what your children do.

Banyaga: My eldest daughter is married and takes care of her family. She has a bachelor’s degree in English from Penn State. My second daughter is a patent lawyer. She did her doctorate in law at Emory and a chemical engineering degree at the University of Maryland. Now she works for the government, in Denver, Colorado. My last child, my son RK, has an MBA from Penn State. My wife Judith also has an MBA and a master’s degree in French literature, both from Penn State. She has been a realtor since 1996.

RK is interested in something very unusual, cryptocurrency. You have heard about that?

Jackson: I have, but I can’t say I understand it! I can’t understand why people buy cryptocurrencies.

Banyaga: I don’t understand it either!

Jackson: But it can be lucrative.

Banyaga: Or it might make you very poor!