by Jean Berko Gleason

I would like to begin these remarks by thanking everyone on behalf of our family — myself and our daughters, Katherine, Pam, and Cynthia — for the outpouring of hundreds of messages that we have received about Andy and your friendship with him. A number of themes stood out in these messages: you often talked of his brilliance, his kindness, his sense of humor, his generosity, fairness, and welcoming spirit. Newcomers to the Society of Fellows or to the mathematics department at Harvard were not only made to feel at home, but they had rigorous intellectual discussions with Andy in which they found that their views and opinions were both challenged and respected. An hour’s talk left you with weeks of things to think about.

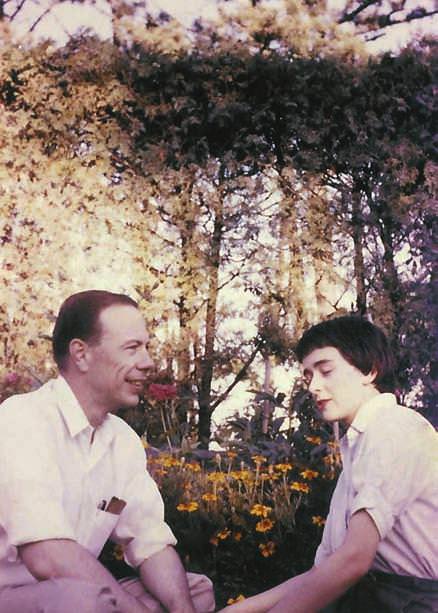

Others will speak about Andrew Gleason’s lasting contributions to science and to education. I would like to tell you a little bit about him as a person. I met Andy Gleason by accident over fifty years ago. I was a graduate student at Radcliffe College and he was a young Harvard professor, luckily not in my field, which is psycholinguistics. But I had friends in the Harvard mathematics department who were giving a party. When they told me that the famous Tom Lehrer was going to be at the party and that he might also play the piano and sing, I decided to go. Tom did sing, but I never got across the crowded room to meet him. Instead I met this slim young fellow who invited me out to dinner. So that was the beginning of our relationship, which soon led to a marriage that lasted forty-nine years. Since Andy was not the type of person to talk about himself very much, I’d like to tell you a few things about his origins that you may not know.

You may think of Andy as quintessentially New England, white Anglo-Saxon Protestant — the blue eyes, the pale skin, the disinterest in worldly goods. It is mostly true: his father was a member of the Mayflower Society. Andy was a direct descendent of four people who came on the Mayflower, including Mary Chilton, who by tradition was the first woman to come ashore at Plymouth Rock. But perhaps you did not know that Andy was also just a little bit Italian. His middle name, Mattei, came from his grandfather, Andrew Mattei, an Italian-Swiss winemaker who came to Fresno, California, and established vineyards, where he prospered and produced prizewinning wine. Andrew Mattei’s daughter, Theodolinda Mattei, went to Mills College in California and on graduation did what all wealthy, well-bred young women of the day did: she embarked on the grand tour, a trip around the world via steamship, with, of course, a chaperone. On board ship Theodolinda met a dashing young botanist on his way to collect exotic plant specimens. This quickly became a classic shipboard romance and led to the marriage in 1915 of Theodolinda Mattei and Henry Allan Gleason, who was to become not only Andrew’s father but a famous botanist, chief curator of the New York Botanical Garden, and early taxonomist and ecologist whose work is still cited — he wrote the classic works on the plants of North America. Andy had an older brother, Henry Allan Gleason Jr.; Andy’s older sister, Anne, is one of the smartest people I have ever met.

We were married on January 26, 1959. This was actually the day of the final examination in the course Andy was teaching. So he gave out the blue books at 2:15 and came here to the Appleton Chapel of The Memorial Church to get married at 3 p.m. We took a wedding trip to New Orleans, and he did not bring the exams. Over the next forty-nine years we raised our three talented daughters, bought a house in Cambridge and a wonderful house on a lake in Maine, and traveled all over the world, sometimes to see some of Andy’s favorite things, which included total eclipses of the sun, most recently in 2006 sailing off the coast of Turkey. We were both teaching, of course, and maintaining our own careers, but we managed to have a lot of fun too. During those forty-nine years Andy maintained the calm spirit he was known for and really never raised his voice in anger. He had a great sense of humor and was extraordinarily generous, giving away surprisingly large sums of money, often to his favorite schools: Harvard and his alma mater, Yale.

Because mathematics was truly his calling, Andy never stopped doing mathematics. He carried a clipboard with him even around the house and filled sheets of paper with ideas and mysterious (to me) numbers. When he was in the hospital during his last weeks, visitors found him thinking deeply about new problems. He was an eminent mathematician. He was also a good man, and he led a good life. We are sorry it did not last a little longer.