by Rob Kirby

Beginnings

My paternal grandfather was named Cromwell Percy Kirby, and therein lies some family lore. Apparently a Percy fought for Oliver Cromwell in the English Civil Wars (1642–1651) and was rewarded with land. The next eight generations of oldest sons died in battle, fighting either for or against the king. Much later in time (and still on English shores), a Percy daughter married a Hackshaw and a Hackshaw daughter married my great-grandfather. The couple left England (perhaps for better air) in 1870 to homestead in Nebraska. My grandfather, one of nine children, was born there in 1873. They lived in a sod house, dug part way into a hillside, a full day’s wagon ride from the nearest town. Cromwell became a small town Baptist minister, and eventually my father, Bernard Cromwell Kirby, was born in Indianapolis in 1907. He aimed to become a minister and went to Denison College (a Baptist school) where he met my mother Pauline Robion.

Mom was born in Chicago in 1907 to a French immigrant father, Abram Robion, and a German immigrant mother, Edith Fisher. Her family lived in Oak Park and she also eventually went to Denison — a year ahead of my father, who had worked for a year after high school to help support his family.

Dad worked for a company making saxophones in Elkhart Indiana, for a steel foundry, and had a string of those old-fashioned gadgets into which you put a penny and got a handful of peanuts. He said he bought a car for \$100 in order to make the rounds replenishing peanuts (I’ve never understood the economics of this).

My mother taught English for a year in the coal mining town of Bluefield, West Virginia, and then my parents married in 1930. They both got jobs in social work in Chicago and took a grad course or two at the University of Chicago’s School of Social Work. My Dad had decided not to pursue the ministry, to his father’s deep regret, but to save the world through social action. In the depths of the Depression, my parents were informed that the city could not employ more than one person in a family, and as my mother was probably more proficient as a social worker, my father left and started organizing for the CIO, the Congress of Industrial Organizations. They’d get him a job, he’d start organizing, he’d get fired, he’d get another job. In his free time he ran for the Chicago City Council as a Socialist, and got more votes than he expected because the Chicago machine liked the Communists even less that the Socialists and switched some Communist votes his way, or so the story goes.

I was born in 1938, and though Mom went back to work, she fairly soon decided she’d rather stay home and raise her son. Dad tried his hand at writing fiction for a living — short, boy-meets-girl, boy-loses-girl, boy-gets-girl Saturday Evening Post-type stories, but although they weren’t bad, they didn’t sell. So he took the “Go west, young man” route, got a job overseeing welfare in the north half of Idaho, and we found ourselves on Military Drive in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho in 1940. Dad drove combines during the wheat harvesting season in the Palouse country. He had quite a variety of moonlighting jobs during his life, including changing tires in a truck stop, butchering rabbits, collecting bills, driving a taxi and others I can’t remember.

World War II began and Dad was in danger of being drafted. He was a quiet, conscientious objector, not a popular position, so he lost a few jobs when his views were discovered. We lived in Walla Walla, Washington (a county job with a deferment) where my brother Douglas was born in October 1943, then two months in Yakima in early 1945, and then Spokane with the War Housing Authority.

School

I learned arithmetic while playing games with my mother and reading as she read to me. Mom got me into first grade at five and a half, but after a few weeks the teacher told her that it wasn’t working, that I was not participating and just looking out the window. But they realized I was just bored, already knowing the material, so with extra material it worked out ok. I had already gotten into the habit of not listening to the teacher, a habit that continues to this day, a habit that means I rarely learn much from lectures.

I was a quiet child, but perhaps with a rebellious streak. For example, in January 1945, when I was not quite seven, I attended a Yakima public school where I got lunch which I was required to finish. I hated macaroni and cheese, served every Thursday, so on one Thursday I went out to the school bus but didn’t get on. Instead I went through the trees and played in the nearby creek until the bus returned and I came home. No one found out, but seven hours in January without lunch probably cured me of playing hooky.

When I was 8, my grandfather visited and taught me the rules of chess. I bugged him incessantly to play more games, so got restricted to one per day.

The war ended and Dad heard of an opportunity to teach at the newly founded Farragut College and Technical Institute at the site of the decommissioned Farragut Naval Base on Lake Pend Oreille in northern Idaho. Over Thanksgiving, 1946, we moved and he took over, mid-semester, four courses in the social sciences and humanities. As we arrived, Mom developed a weakness in her legs and eventually a hospital in Spokane decided she had polio — at age 39! She came home Christmas Eve to a house with a wood stove, an overworked husband and two boys, 8 and 3, and was bedridden.

Some 18 months later, Mom and Doug took the train (I’m not sure how, but surely a wheelchair was involved) back to Chicago where they stayed with Mom’s sister while she was “rehabilitated”, getting a full brace on one leg and a half brace on the other, and learned to walk with crutches and even drive a specially outfitted car. But after driving across the country to Spokane, her old reflexes took over in the midst of traffic and she crashed into a store’s plate glass window, injuring no one, fortunately. She never drove again.

I was in a three-room schoolhouse in Farragut, the best school I went to, because while in 4th grade I listened to the 5th graders and then skipped that class. After school and during summers I headed outdoors, unsupervised, and learned how to negotiate the woods and lake by myself or with a friend or two. A great growing-up experience (later I told my children they were disadvantaged growing up in Berkeley, by comparison).

In Farragut, when I was nine, Dad got me a job at the College library shelving books, three morning hours three days a week, for the princely sum of \$.25/hour. I got bored and asked Dad if I could quit. He remarked that he had to work to give me a very modest allowance, so what did it mean that I didn’t want to work to enhance my spending money? I got the message, a good one.

Dad discovered he liked teaching and decided to go to graduate school in sociology at the University of Washington. We settled into Edmonds, Washington where I spent grades 7–12. We were poor, living on a TA’s salary and Dad’s moonlighting. When Dad passed his Ph.D. orals, we celebrated by splitting a pint of cheap Neapolitan ice cream. But it was a good life. I worked four summers in a nursery, saving for college, and learned a bit about gardening. I also had to do the house cleaning for those six years, a full cleaning (dusting, vacuuming, floor washing) once a week and a half-clean midweek. This led to a fair number of disputes since my mother’s standards were much higher than mine. It was very frustrating for her to be unable to get things done as she would have done them.

I loved playing games: sports, chess, and the popular card games of those days (anyone remember Rook or Flinch?). But there was always a shortage of opponents (we were living in a semirural area on a dirt road and the nearest friends were two miles away), and a tennis match meant finding an old slightly bent racket, some half dead balls, and a court with grass in the cracks and a sagging net. In retrospect, this still seems better to me than being driven to tennis lessons on a snazzy court with the best equipment where you spend half your time listening to a coach.

There were few chess players around, but occasionally I ended up at the University of Washington Chess Club, which was worth a story in the Seattle papers.

High school wasn’t hard, and I ended up as valedictorian and wrote and memorized a speech on the “Challenge of nonconformity”.

College

When it came time to apply to college, I knew that I didn’t like to write and liked math best of my academic subjects, so I decided that Caltech was the place I’d like to go. I also applied to Reed and to the University of Chicago because of my parents connections with it (how otherwise would I have known of its existence as it did not have a football team?). But only Chicago gave me a scholarship (\$1200, yet with tuition only \$690, I could make ends meet) so there I went.

It was wonderful. I’d been starved for boys to play games with and suddenly I was in a dorm full of boys waiting to be lured into games (particularly chess) and small-time sports (they had a great intramural program).

At that time, in 1954, Chicago offered 14 year-long courses with the yearly grade being determined by a six-hour exam at the end of the year. The idea was to give the students the freedom to choose what to focus on at any given time, but ensure that by the end of the year they had learned the subject. The exams were very well written but tended to favor the smart rather than the hard worker. There were three courses in each of the physical sciences, social sciences and humanities, as well as one course each in philosophy (called OMP, organization, methods, and principles of knowledge), English, history, a language of one’s choosing, and a general math course. There were placement exams which you took upon entering, and it was possible to do well enough in all the exams to be immediately given a BA. I was exempted from four, math, english, and the first of the natural and social sciences.

There were quite a few early entrants, some younger than 16, and too many didn’t handle the academic freedom well, so the University eventually transitioned to a more traditional course and exam system. I found myself immersed in games, learned some academics, but got more Fs than As. For example in my third year I signed up with a friend for an electricity and magnetism lab course, which required ten three-hour labs in a quarter. After five weeks, we figured two labs per week was doable. That notion died by the end of the eighth week when five labs per week was obviously not going to happen.

I joined a fraternity, Psi Upsilon, in my third year. That seems odd now, but Chicago under Robert Maynard Hutchins had not just quit football but also banned fraternities for undergraduates. Some fraternities continued to exist as residences for grad students with some fraternity traditions maintained, e.g., new members being chosen by the old ones. A bunch of my friends joined Psi U, and I followed suit, being admitted to an older group of GIs, grad students and older undergrads. They were a good bunch. Our fraternity house was located directly across the street from Bartlett Gym, and I imagine pedestrians must occasionally have been startled by the sight of a scantily clad young man racing across the street through winter snow dodging slush-puddles to get to or from the gym.

During the summers of 1956–1959, I had summer jobs or internships at the Navy Electronics Lab on Point Loma in San Diego. They had a state-of-the-art computer and I was asked to write a program in which the computer would learn how to play tic-tac-toe. I did this in machine language (Fortran existed but I don’t remember what else). The boss suggested I submit it to the Journal of the Association for Computing Machinery. They accepted it (to my great surprise — maybe they were desperate in those days) but asked for revisions. But I was lazy, hated to polish, and didn’t think much of what I’d done, so I never made the revisions. And thus missed my chance to really get into computers in the very early days.

But my time at the Lab nonetheless effected my life quite deeply: a coworker at the Lab introduced me to rock climbing — and Tahquitz Rock — and another coworker organized a nine-day hike in the Sierras, so my summers at the Lab marked the beginning of years of rock climbing, hiking and mountain climbing.

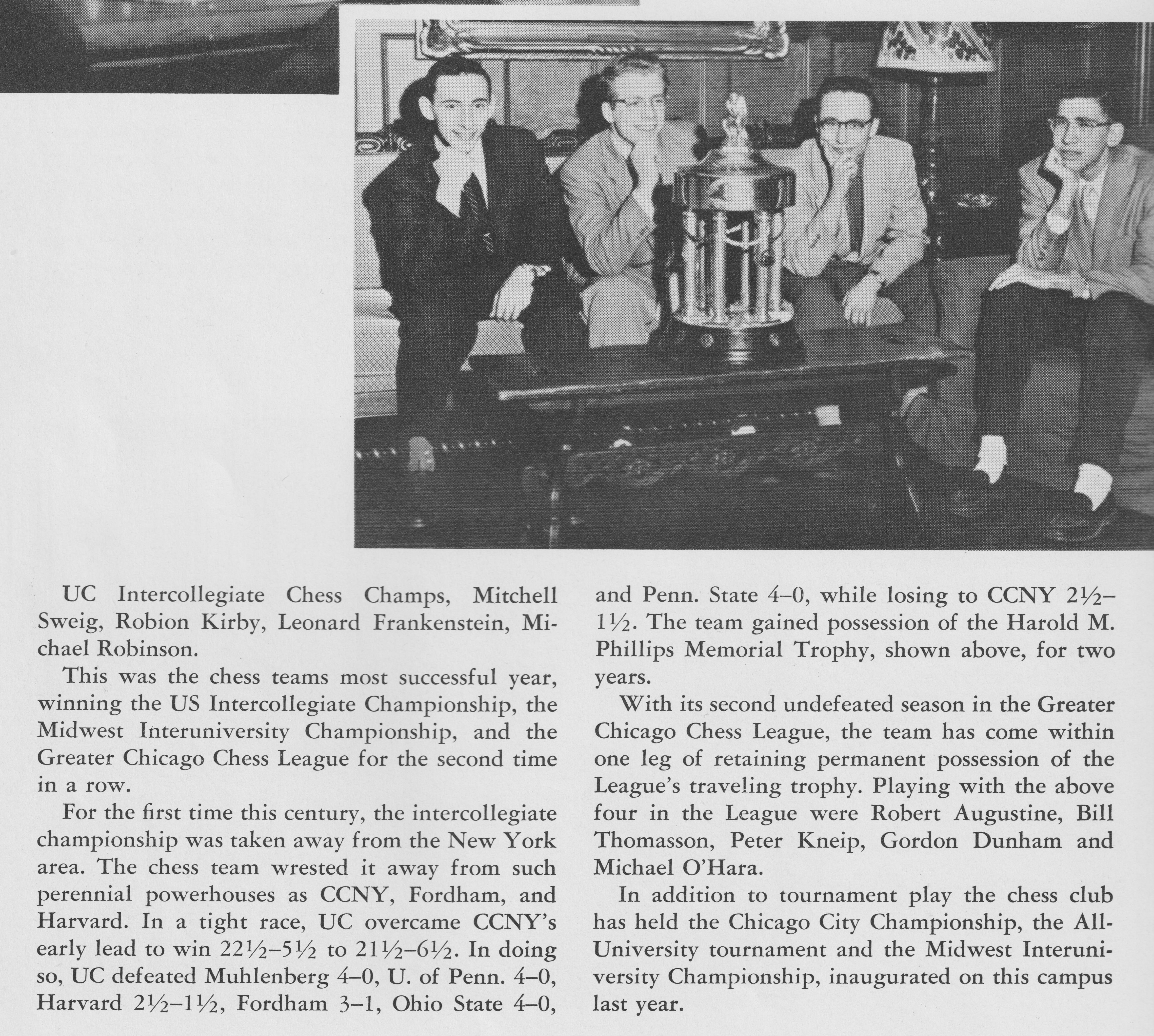

While at Chicago, I matured as a chess player, and played first or second board on our college team, alongside Lester Frankenstein, Mike Robinson and Mitch Sweig. We won the Intercollegiate Championship in December of 1956 and again in 1958 (it was only held every other year). Typically we played seven rounds in those competitions. You could determine the winning team by adding up total points, counting \( .5 \) for draws (28 max) or by adding up match wins (max 7). In 1956 the tournament winner was decided by total points, and so we won, though we would have been second if the tally had been made by match points. We were upstarts, and the eastern powerhouses were displeased, so they switched to a match point tally for the 1958 contest. On that occasion, we won the match point total and so the tournament, and would have lost if the tally had been done by total points. In those days, Sports Illustrated thought chess was a sport, and we got a nice write-up of our 1956 victory in the January 14, 1957 issue.

I continued to play chess until 1968, but didn’t study the game much after college. I did get ranked as high as 25th in the US at one point, but discovered that math was a much better game. I never played Bobby Fischer, but did have a few games against international grandmasters and didn’t do badly. I was Illinois state champion while an undergrad, and that may have helped deflect attention for a time from my poor grades.

I lost my scholarship after three years (no surprise) and also flunked German (a full-year course with the grade determined by an end-of-the-year exam). I took it again in my fourth year and was lucky; I flunked it again (it is hard to pass an exam with a serious oral portion if you have never gone to class). I say “lucky” because it meant I had to go back for a fifth year, during which I took seven of the eight grad courses in math which were covered by the Masters Exam. And passed German with a D. So I had a BS by June 1959.

Grad school

I don’t remember worrying, or even thinking much, about the future, but I did apply to Chicago for grad school in math (I did not apply anywhere else for who would take me with my record), arguing that I had already taken seven of the eight courses and was thus on the verge of being ready for the Masters Exam. I was admitted provisionally with the proviso that I get grades closer to B than C. In the fall quarter I received a B, a C and a Pass, not closer to B than C but no one objected.

In those days you could get four grades on the Masters Exam: (i) pass with financial support; (ii) pass but with no financial support; (iii) pass with the recommendation that you go elsewhere; and (iv) fail. I passed at the lowest level, but ignored the recommendation that I go elsewhere, and borrowed a bit of money to continue at UC in the fall of 1960. For support, I applied for teaching at Roosevelt University, a night school in downtown Chicago. Saunders Mac Lane wrote a recommendation and I got a job (three courses, all precalculus, at three hours/week each), enough to pay my way.

But during the summer (1960) I met my future wife, Ingrid. She had finished her freshman year at Berkeley in German Literature and we met in San Diego where our parents lived. I was headed back to Chicago that fall, but decided I would transfer to Berkeley for the obvious reason. I applied to Berkeley figuring that an MS from Chicago would get me in. I packed up my car and drove out to Berkeley only to discover I wasn’t admitted. A petition didn’t help.

So I went back to Chicago in the fall of 1961 having loitered through the previous year under the assumption I was leaving. Now I had to get serious and think about the Ph.D. qualifying exam, a two-hour oral exam on two topics. I chose topology, with topics in Hu’s book Homotopy Theory, and finite group theory, with some of the chapters in Marshall Hall’s book The Theory of Groups. They wanted breadth, and homological algebra was not far enough from algebraic topology.

I took the exam in the fall of 1961, my second year of grad school. Of course I failed. But there was a second chance. I got good advice: to start talking math, join the math community and pick up folklore. I hadn’t taken a mock qual or anything remotely like that. My friends were jocks and outside the math community. I didn’t have an office where I would naturally meet math grads, but I started going to tea.

Norman Steenrod was visiting that year, and a notable event for me occurred at tea where I eavesdropped on his explanation of the Hopf map, \( S^3 \to S^2 \), where the fibers are the unit circle in the \( xy \)-plane and the \( z \)-axis union infinity, as well as in all the \( (1,1) \)-torus knots in the complement. The map \( (z,w) \to [z,w] \) never enlightened me, but this marvelous picture did.

One of my qual examiners was a postdoc named George McCarty (he later wrote a text book on algebraic topology) who was friendly and asked if I’d be interested in his Ph.D. thesis on the homotopy groups of homeomorphisms of a manifold.

I took the Ph.D. qual again in the spring of 1962 and passed, but was told that my performance in topology was weak and I shouldn’t choose that subject for a thesis. So I dropped in on Mac Lane to ask him about being my adviser. He asked what I was interested in and I said group theory, homological algebra and topological manifolds (McCarty’s thesis). Mac Lane wisely advised me to go home for the summer and think about the three and talk to him again in the fall. I never touched the first two, and thought some about topological manifolds.

In the fall, now married, I approached Eldon Dyer asking him to be my adviser. Dick Lashof would have been the more geometric and natural choice, but he’d been on my qual committee and presumably had made the negative comment about working in topology, whereas Dyer had been away on sabbatical. Dyer did not answer as I expected, for I figured he’d want to look at my file. I periodically dropped in on Dyer with math questions, but never asked him for an answer; I’d asked, and now the ball was in his court. Later I found out from another mathematician that Dyer eventually realized that I had become his informal, hence formal, student.

I now began to be a serious mathematician, discovering that math was a better game than all my others. Research appealed to me, something like sorting out a difficult end game in chess. I got to know Walter Daum, a fellow Dyer student who had accomplished in four years what had taken me seven to do. We ran a two-man hour-long seminar meeting every day. Preparation was frowned upon and one of us would stand at the blackboard, writing down the next theorem in Zeeman’s notes or a Stallings paper or Brown’s proof of the Schoenflies theorem, which we would try to prove on our own before looking for a hint, proceeding slowly but learning a lot. This seminar was probably the most crucial educational experience in my young life. (Later, it was learning math with my graduate students, both while they were students and then later on.)

Later years

Family

My son Rolf was born in March, 1968, and then Kate came along in April 1971. They have been a great joy in my life. Rolf is a medical doctor and Kate a biostatistician, and both are very much outdoors people. We’ve hiked, skied, rock climbed and run together many times.

My marriage to Ingrid ended in the late 1970s and for a few years I was a single father with custody of both Rolf and Kate. They were such sensible kids it was pretty easy. In 1981 I met Linda and we married in April, 1982. She had two daughters of similar ages, Kara and Erika, so we had an interesting time merging the two families, with great results.

Linda liked to travel, so we six spent the summer of 1981 in Cambridge; the fall of 1982 at IMPA in Rio de Janeiro; the spring of 1983 in Washington D. C. (University of Maryland); and the summer of 1984 again in Cambridge. By then it became harder to get high school-age kids to travel.

Linda’s brothers, Gerry and Bob Slavin, were always fun and we hiked with them many times in the Canyonlands and Grand Canyon (including our honeymoon for six days below the south rim of the Grand Canyon).

My parents died in 1991, Mom on May 23, Dad on June 1. Mom had had a stroke seven years earlier, leaving her completely bedridden, only able to eat with her left fingers, unable to answer a yes–no question, but recognizing us. Her life was as unlucky as mine has been lucky. Dad got non-Hodgkins cancer, and when he spent his last month in the hospital, separated from my Mom, the light seemed to go out in her eyes. Two days before Dad died, he asked me to help him get up from bed. It was obviously painful and I asked him if he really wanted to get up. He replied, “I’m not yet ready to have taken my last steps”. As I write this in September, 2021, after not hiking last summer in the High Sierras, I wonder if I have already taken my last multiday hike there, after 60 splendid years of doing so.

Hiking and mountaineering

I mentioned above hiking in the Sierras in 1959, and I want to return to that expedition for a moment. My brother Doug, still 15, joined me on that trip and we intended to climb the classic route on the east face of Mount Whitney. In those days you got a climbing rope by writing to the Seattle Coop (now REI) for a nylon 120 foot rope that tended to kink; you got climbing shoes by drawing an outline of your foot on paper and sending it to the Ski Hut in Berkeley (which returned a pair of not-too-snug shoes); and you got a pack by writing to Kelty in Burbank. No store in San Diego sold such stuff! (Ten years later every kid had a down jacket because it was cool, but not in 1959).

Doug and I carried this gear (plus piton hammer and pitons) and 200 feet of manila hemp rope in case we were forced to rappel off Whitney. We went over Kearsarge Pass, headed south over Forester’s Pass, and went past Lake Tulainyo (the lake at the highest altitude in the US) around to East Face Lake below Mt. Whitney. We had carried a canned ham (freeze dried food was rare) but were too tired to eat it. The next day’s ascent was straightforward (only a few piton placements and it was my brother who suffered carrying the rappel rope), including the descent down the Mountaineer’s Route.

That duress of that experience could have killed Doug’s interest in mountains but 25 years later we were together again for another big adventure: an ascent of Mt. McKinley. In those days, one of every 300 people attempting to summit McKinley died. Those are not good odds. The previous year a famous Japanese climber soloed McKinley in the winter, radioed from the top and was never seen again. The other death was that of a guide who, descending on skis during a white-out, had come to a stop just in time at the edge of a crevasse only to fall in when the edge gave way. Well, we weren’t going to solo in the winter nor ski in a white-out; in fact we packed 21 days of food and fuel (used only half), advanced slowly so as to acclimate well, and then had good luck on our summit day for the wind was mild. It took 14 days, two for the descent.

Later Doug and I tried twice to climb Mt. Rainier and were turned back by bad weather (which could kill climbers); Doug and Kate summited on a subsequent attempt.

In 2010 Doug talked ten of the family into climbing Kilimanjaro. The ten were my cousin Kay, 72, me, Linda, Doug and wife Gail and son Cameron, Rolf and wife Jannell, Kate and then husband Damon. There are rules for climbing Kili, one being that you must hire locals as guides and porters, so we had around 36 who guided, put up tents, carried gear, brought fresh eggs, chicken and watermelon, etc. It was not a wilderness experience. The comparison with the Sierras is interesting. Most traffic in the High Sierras occurs in August and September and then the Sierras have ten months to recover. Kili can be climbed year-round and the total number of people in any given party is pretty much triple the number of “climbers”, because of the porters. Kili is a volcano and most precipitation sinks into the ground, so there are few streams and lakes. The Sierras are a new granite range dotted by beautiful lakes and streams. So, while Kili was an interesting experience, I can’t heartily recommend it.

Doug wanted to climb the highest mountain in the world, measured by the distance from the center of the earth. Because the earth is not round, but wider at the Equator, the highest such mountain is not Everest, but Chimborazo in Equador, at 6,263 meters (20,548 feet). I wasn’t sufficiently interested, so he went there in December 2012 with his son, Cameron, a friend and two guides. On December 22, he was descending from a warm-up climb on Cotopaxi (5897 meters) at dawn, before the sun hit the treacherous slopes. He sat down with his guide on a rock outcropping to have a drink of water. He looked at the beautiful view and exclaimed, “Isn’t life wonderful!”, then slumped over and died. It was a glorious way to go, but it was much too soon for the rest of us.

Twice, in 1992 and 2002, Rolf and I hiked for two-week-long stretches on the north slope of the Brooks Range in Alaska. During the first trip, we spent twelve days with no sign that humans had ever existed, no hikers, no trails, no planes overhead, just hundreds of caribou and a fleeting glance at a wolf. It felt really primeval.

We did have a memorable encounter with a grizzly bear and her cub. We were walking at the edge of a wide (\( \sim \)25 yards), shallow, half-dry stream bed when we saw the grizzly emerge from low bushes on the far shore. I took three photos as she drew opposite us. As I put my camera away in my shirt pocket, she charged. Imagine in football a wide receiver catching a pass on the 25-yard line and then arriving in the end zone in no time; the bear is faster. We were surprised and even at the time could not remember how we reacted. We were lucky that it was a bluff, for about 10 yards from us she turned away and her cub scrambled to catch up.

A few years later at a Georgia topology conference, Cliff Taubes was lecturing and half-way through he said he was going to wake up his audience by telling a story before going back to math. I was speaking in the next slot, so I did the same, telling the grizzly bear story. No one, including me, remembers my math talk, but everyone remembers the grizzly bear story!

I did most of my rock climbing and kayaking with Dennis Johnson, and touch on some of those expeditions in my brief biography of him for Celebratio.

Nuclear disarmament

In 1983, I saw a letter to the editor by Stephen Salter in the journal Nature; it described a way of reducing nuclear arms using the idea of cutting a cake fairly so that all cake eaters are happy.1 I found the idea interesting and wrote an elaboration which can be found here.

My version is to allow the US and the USSR to assign values to each of their own nuclear arms, with the total values adding up to an agreed upon constant N. Then, the US would choose arms belonging to the USSR whose values (already assigned by the USSR) added up to a constant M and these would be destroyed. Similarly, using the same M, the USSR would choose US arms to be destroyed.

Because the values of a given arm would likely differ between the two countries, the US would be able to destroy USSR arms that we considered more valuable than the USSR did, and conversely. Thus, as with a chocolate cake, both parties should be pleased with the outcome, and continue with further iterations.

For example, I like icing better than you, you like cherries on the icing more than I do, and we equally like the cake itself. Then, if I am the cutter, I will try to cut roughly equal pieces but with one having more icing and the other more cherries. You choose the slice with more cherries and I then am happy with the extra icing. For two people this is simple2 but for \( n \) people, it gets much more complicated (as Erica Klarreich explains in “How to cut cake fairly and finally eat it too,” Quanta magazine, October 6, 2016).

Such schemes appeal to the mathematically minded, but seem not to go far in the real world.

Band manager

I overlapped with Cameron Gordon and Justin Roberts on several visits to Warwick (thanks to Colin Rourke for making them possible) and enjoyed listening to them playing acoustic guitars, usually covering old rock songs. I offered enthusiasm and the tiniest bit of organizing and soon both were playing at various birthday fests: mine in 1998, 2008 and 2018 (the latter was mostly for Abby Thompson and her adviser Scharlemann), for Scharlemann’s 60th, for Gordon’s 60th, for Mike Freedman’s 60th and a few others. Cameron and Justin were often joined by Eli Grigsby, an excellent vocalist, Taiyo Inoue on bass, and various drummers.

A book on public policy

I’ve left to the last a topic/project which took a considerable amount of time and thought and which grew out of years of discussions with my father and brother about how to “save the world”. I wrote the first words in September 2007 just below Bishop Pass in the Sierras while waiting for Doug and the others to wake up. Over the next ten years I would stop while driving somewhere and write a few pages. After a while I put these bits in some order and started a \( \mathrm{\TeX} \) file. Eventually it turned into a manuscript. Some friends read it and made comments, usually to tone it down so as not to offend. It still has not yet gone to a publisher.