by Loïc Merel

1. “By pure thought”

In the preface of his Disquisitiones Arithmeticae, Gauss proclaimed (or insisted) that diophantine questions do not constitute all of number theory [e10]. A similar distinction seems appropriate when one contemplates the content and legacy of Mazur’s Eisenstein ideal paper. Accordingly, the recurring and fecund theme of congruences between Eisenstein series and other modular forms will be considered first in the context of the torsion theorem, and then for other arithmetical, nondiophantine purposes.

2. From Levi to Ogg, Mazur and Tate

As Schappacher and Schoof realized around 1994 [e46], Mazur’s torsion theorem had been formulated as a conjecture in 1908 by Levi [e4] in his address to the international congress of mathematicians, and seemingly forgotten in the course of the 20th century. It is difficult to trace exhaustively the history of this question. Levi had already noted that it amounts to prove that certain curves (the notation \( X_1(N) \) was an anachronism in 1908) do not have rational points besides the obvious ones (cuspidal, in the modern jargon). He established that no elliptic curve over \( {\mathbf Q} \) admits a rational point of order 14, 16 or 20 [e1], [e2], [e2], [e3]. His proof was based on the method of descent, applied to curves of genus no larger than 1, the very technique dating back to Fermat and employed by many continuators of Levi, including, in a crowning achievement, by Mazur. Considering that the question was asked at the ICM, and that significant partial results were obtained, it is difficult to fault Levi for having failed to durably bring his conjecture to the attention of his contemporaries and successors, and therefore to deny him the priority for his prediction. Levi’s work preceded Mordell’s proof of the finite generation of (what we call nowadays) the Mordell–Weil group, published in 1922 [e5].

Billing and Mahler [e6] (in 1940), with an ulterior contribution of Nagell [e9] (in 1952) proved, still by studying curves of genus 1, that no elliptic curve over \( {\mathbf Q} \) possesses a point of order 11, 15 or 24. Levi seems to have been forgotten by 1949, at least by Nagell, who reaffirmed the torsion conjecture [e8] without apparent awareness of Levi’s work. In [e16], Ogg ruled out 17 as a possible torsion prime. He proposed a geometric philosophy: \( X_1(N) \) should have noncuspidal \( {\mathbf Q} \)-rational points if and only if the genus of \( X_1(N) \) is 0 (i.e., \( N\leq 10 \) or \( N=12 \)) [e21]. This was known to be equivalent to the torsion conjecture. Thus the once forgotten torsion conjecture of Levi has sometimes been referred to as Ogg’s conjecture.

All this was part of a wider background of results and conjectures of which here is a sample. In 1967, Cassels attributed to the folklore the belief that the order of torsion of an elliptic curve over a number field \( K \) is bounded in terms of \( K \) only [e11]. Shafarevich had asked sometime before 1972 whether the bound in Cassels’ folklore conjecture would depend only on the degree of \( K \) over \( {\mathbf Q} \) [e18]. Manin proved in 1967 that, for any prime number \( p \) and any number field \( K \), the \( p \)-primary torsion of an elliptic curve over \( K \) is bounded in terms of \( p \) and \( K \) only [e13]. Both Dem’janenko and Hellegouarch had noted an intriguing connection between hypothetical solutions of Fermat’s equation for the prime exponent \( p \) and the \( p \)-torsion of what would later be called the Frey elliptic curve [e14], [e15]. Serre had proved his open image theorem in 1972 [e19], setting forth the following statement:

Let \( E \) be an elliptic curve over a number field \( K \) without complex multiplications over \( {\bar K} \). For \( l \) prime number, denote by \( E_{l} \) the group of \( l \)-division points of \( E \). There exists a

number \( N \)such that the representation \( \operatorname{Gal}({\bar{\mathbf Q}}/{\mathbf Q})\rightarrow \operatorname{Aut}(E_l) \) is surjective for \( l > N \).

Serre asked about a uniform version [e19]:

[…] peut-on prendre pour \( N \) un entier qui ne dépende que de \( K \) et pas de \( E \)?

3. The work of Mazur and Tate on 13-torsion

Here is the argument that Mazur and Tate employed to show that \( X_1(13) \) has no \( {\mathbf Q} \)-rational points besides its cusps [1]. By “pure thought”, the authors meant that, contra their predecessors, they had no use of any model for such a modular curve. They proceeded by embedding the curve \( X_1(13) \) in its jacobian \( J_1(13) \), and then studying the \( {\mathbf Q} \)-rational points of \( J_1(13) \).

Such an approach had been familiar for a long time. In particular, Chabauty proved that, provided the rank \( r \) of Mordell–Weil group of the jacobian \( J \) of a curve \( X \) over \( {\mathbf Q} \) is strictly smaller than the genus \( g \) of \( X \), then \( X({\mathbf Q}) \) is finite [e7]. The condition \( r < g \) is Chabauty’s condition, a fundamental guiding principle to this day. But establishing finiteness differs significantly from providing the full list of rational points. Faltings’ theorem [e27], proved in 1983 and famously ineffective, would have been of no help to Mazur and Tate. In the setting of modular curves, the latter authors and Ogg combined an understanding of the arithmetic of \( J \) with some knowledge of the geometry of the map \( X\rightarrow J \). Their successors would follow variations of this basic plan (see Program B below).

The key arithmetic argument is that the group \( J_1(13)({\mathbf Q}) \) is cyclic of order 19 and a fortiori finite. The proof is summarized with admirable concision in the third paragraph of [1]:

The possibility that this could be done occurred to us when Ogg passed through our town and mentioned that he had discovered a point of order 19 on the 2-dimensional abelian variety \( J \). It seemed (to us and to Swinnerton-Dyer) that if such an abelian variety \( J \), which has bad reduction at only one prime, and has a sizeable number of endomorphisms, has a point of order 19, it is not entitled to have any other points.

Descent has been used by several predecessors of Mazur and Tate including Levi, but accommodating the “sizable number of endomorphisms” (i.e., the descent a with coefficients in a Hecke algebra) was a key innovation.

Thus the \( {\mathbf Q} \)-rational points of \( X_1(13) \) are to be found among the 19 \( {\mathbf Q} \)-rational points of \( J_1(13) \). It was known that only six of those points come from \( X_1(13) \), and they all come from the cusps.

From then on, the torsion conjecture could be thought of as a diophantine problem devoid of diophantine equations.

4. The Eisenstein ideal and torsion of prime order

We follow throughout Mazur’s unusual choice of notation: let \( N \) be a prime number. The essential step to prove the torsion conjecture consists in proving that \( X_1(N) \) has no rational points, besides its cusps, for \( N=11 \) or \( N > 13 \) (call this the prime torsion conjecture). The additional arguments needed to obtain the full torsion conjecture have already been mentioned or reside in two articles of Ligozat [e20] and Kubert [e23].

But the Mazur–Tate argument can not work for every value of \( N \) since

\( J_1(N)({\mathbf Q}) \) was suspected (and Mazur confirmed this suspicion in

[4],

Theorem 3) to be infinite except for finitely many

values of \( N \). The modification introduced by Mazur consists in

identifying a nonzero quotient abelian variety \( \tilde J \) of \( J_1(N) \)

such that \( \tilde J({\mathbf Q}) \) is finite or, more precisely, \( \tilde J \)

is the largest quotient of \( J_0(N) \) for which the method of descent

can be used to establish the finiteness of \( \tilde J({\mathbf Q}) \).

For this, Mazur noted that the ring of endomorphisms (over \( {\mathbf Q} \)) of \( J_0(N) \) identifies to the (commutative) Hecke algebra \( {\mathbf T} \) (the subring of the endomorphisms of \( J_0(N) \) generated by Hecke operators \( T_l \) for \( l \) prime number \( l\ne N \), and by the Atkin–Lehner operator \( W_N \)). The Eisenstein ideal \( {\mathcal I} \) of \( \mathbf{T} \) is generated by the operators that would annihilate the single Eisenstein series of weight 2 for \( \Gamma_0(N) \). In practice, it is spanned by the operators \( T_l-(l+1) \) for \( l \) prime number \( l\ne N \), and by \( 1+W_N \). Mazur established two basic properties: the quotient ring \( {\mathbf T}/{\mathcal I} \) is isomorphic to \( {\mathbf Z}/n{\mathbf Z} \), where \( n \) is the numerator of \( (N-1)/12 \), reflecting the fact that \( (N-1)/24 \) is the constant coefficient (essentially a Bernoulli number) of the Eisenstein series of weight 2 for \( {\Gamma}_0(N) \). The second property lies deeper: \( {\mathcal I}/{\mathcal I}^2 \) is also a cyclic group of order \( n \), but it identifies to the group \( (\mathbf{Z}/N{\mathbf Z})^\times/\mu_{12} \) where \( \mu_{12} \) is the group of 12th roots of unity. The latter identification is obtained by \( T_l-(l+1)\mapsto \text{class of } l^{(l-1)/2} \).

Denote by \( {\mathbf T}_{\mathcal I} \) the \( \mathcal I \)-adic completion of \( {\mathbf T} \). Then \( \tilde J \) is the largest quotient of \( J_0(N) \) on which \( {\mathbf T} \) acts through \( {\mathbf T}\rightarrow{\mathbf T}_{\mathcal I} \). Hence, \( \tilde J \) is called the Eisenstein quotient of \( J_0(N) \). The abelian variety \( \tilde J \) is trivial if and only if \( n=1 \), i.e., \( N \) is equal to 2, 3, 5, 7 or 13.

For \( \mathcal M \) maximal ideal in the support of \( \mathcal I \), Mazur considers the \( \mathcal M \)-adic completion of \( {\mathbf T} \) and defines the \( \mathcal M \)-Eisenstein quotient \( {\tilde J}_{\mathcal M} \) of \( {\tilde J} \). The descent of Mazur–Tate can be adapted, delicately in terms of flat cohomology, to show the finiteness of \( {\tilde J}_{\mathcal M}({\mathbf Q}) \), and deduce the finiteness of \( \tilde J(\mathbf{Q}) \). But Mazur is more precise: \( \tilde J({\mathbf Q}) \) is cyclic of order \( n \), and even isomorphic to \( {\mathbf T}/{\mathcal I} \) as a \( \mathbf{T} \)-module. The descent provides in addition a proof of the triviality of the odd, \( \mathcal I \)-primary part of the Tate–Shafarevich group of \( {\tilde J} \).

This enables one to prove two properties of the whole of \( J_0(N) \) conjectured by Ogg. First, the torsion part of \( J_0(N)({\mathbf Q}) \) identifies to the cuspidal subgroup (and to \( \tilde J({\mathbf Q}) \)). The other property is of a dual nature: the maximal subgroup of \( J_0(N) \) of \( \mu \)-type (Cartier dual of a constant group-scheme) is the Shimura subgroup, defined as the kernel of the morphism \( J_0(N)\rightarrow J_1(N) \) deduced from \( X_1(N)\rightarrow X_0(N) \) by Picard functoriality.

The consideration of the finiteness of \( \tilde J({\mathbf Q}) \) combined with the morphism \( \phi : X_1(N)\rightarrow J_1(N)\rightarrow \tilde J \) directly implies the finiteness of \( X_{1}(N)({\mathbf Q}) \) whenever \( \tilde J \) is nonzero. An additional analysis of the geometry of \( \phi \) is required to obtain the prime torsion conjecture. The reasoning of [4] will not be explained here. Indeed, to obtain this desired conclusion, Mazur provided a simpler and stronger argument in the isogeny paper [5].

5. Rational isogenies

The isogeny theorem, obtained by Mazur in 1978 in [5], is a substantial generalization of the torsion theorem.

At the time of [5], it was not known whether the following numbers should be allowed: 39, 65, 91, 125, and 169. This issue was clarified by Kenku and Mestre [e24], [e25] soon afterwards, and might explain the presence of the restrictive qualifier prime in the title of [5].

It is unclear to me how precisely this statement had been expected among specialists. The finiteness of the list is not mentioned as a folklore conjecture in [e11]. It is asked by Serre (see above) [e19], who proposed a bound for non-CM curves. But Serre missed the exceptional prime number \( N=37 \), which deserves a mention. Indeed, Mazur and Swinnerton-Dyer discovered in 1974 that \( X_0(37) \), of genus 2, admits a pair of non-CM, noncuspidal, rational points [2]. Rational points of modular curves are often explained by “geometric reasons” (the relevant modular curve has genus 0, or genus 1, the point corresponds to a CM-elliptic curve or a cusp). An ambitious project would seek to explain thus all algebraic points on modular curves, though the notion of geometric reason needs to be clarified. The finding of Mazur and Swinnerton-Dyer for \( N=37 \) is the first significant hurdle in such a project. Since then, other notable exotic algebraic points have been discovered, e.g., a quadratic point on \( X_0(311) \) by Galbraith [e52] and a cubic point on \( X_1(21) \) by Najman [e63].

The proof of the isogeny theorem, and therefore of the torsion theorem, is based on a single result from [4]: the finiteness of \( \tilde J ({\mathbf Q}) \). Presciently, Mazur found it useful to spell out in axiomatic form what is needed: when \( N \) is equal to 11 or greater than 13, there exists a nontrivial quotient abelian variety \( A \) of \( J_0(N) \) such that \( A({\mathbf Q}) \) is finite. Such a criterion amends Chabauty’s condition: the rank of \( A \) is smaller than the dimension of \( A \) (\( r < d \)). It is harmless to suppose \( A \) optimal, i.e., the morphism \( J_{0}(N)\rightarrow A \) has connected kernel. In effect, Mazur just considered \( A={\tilde J} \) (see below for the progress on Program B with a different quotient \( A \)).

Mazur proceeded as follows. The essential question is to determine for which prime numbers \( N \) there exists an elliptic curve over \( {\mathbf Q} \) admitting a \( {\mathbf Q} \)-rational subgroup \( C \) of order \( N \). Let \( E \) be such an elliptic curve. Mazur proved that \( j(E) \) is an integer away from 2. If not, an odd prime number \( p \) would divide the denominator of \( j(E) \). Then \( (E,C) \) defines a \( {\mathbf Q} \)-rational point \( Q \) on \( X_0(N) \). Extend \( X_0(N) \) to a model \( {\mathcal X}_0(N) \) over \( \operatorname{Spec}{\mathbf Z} \), and the point \( Q \) to a section \( \hat Q \) : \( \operatorname{Spec}\, {\mathbf Z}\rightarrow {\mathcal X}_0(N) \). Since \( j(E) \) is not \( p \)-integral, \( \hat Q \) coincides with a cusp \( \hat Q_0 \) in the fiber at \( p \) of \( {\mathcal X}_0(N) \). Use \( \hat Q_0 \) as a base point to embed \( X_0(N) \) in \( J_0(N) \). Consider the morphism \( \phi \): \( X_0(N)\rightarrow J_0(N)\rightarrow A \). Then \( \phi(Q) \) is torsion since \( A({\mathbf Q}) \) is finite. Denote by \( {\mathcal A} \) the Néron model over \( \operatorname{Spec} {\mathbf Z} \) of \( A \). The morphism \( \phi \) extends to the smooth locus \( {\mathcal X} \) of \( {\mathcal X}_0(N) \) as \( \hat{\phi} \): \( {\mathcal X}\rightarrow {\mathcal A} \). The section \( \hat Q \) belongs to \( \mathcal X \). Furthermore, the order of a \( \mathbf{Q} \)-rational torsion point in an abelian variety is determined in the special fiber at \( p \) (provided \( p > 2 \)). Thus one gets that \( \hat\phi(\hat Q)=\hat\phi(\hat Q_0) \) and \( \hat Q \) coincides with \( \hat Q_0 \) in the fiber at \( p \) of \( A \). Mazur noted that this implies that \( \hat Q=\hat Q_0 \) (a contradiction) provided \( \hat\phi \) is a formal immersion at the cusp \( \hat Q_0 \) in characteristic \( p \). After a delicate reinterpretation in terms of modular forms, this geometric condition turned out to be remarkably simple: \( \hat\phi \) is a formal immersion at the cusp \( \hat Q_0 \) in characteristic \( p \), at least if \( p > 2 \), whenever \( A \) is nontrivial. Thus either \( \tilde J \) is trivial (and \( N=2 \), 3, 5, 7, or 13) or \( j(E) \) is integral away from 2. (A variant of this argument establishes that \( N=2 \), 3, 5, 7, 13 or 17 or \( j(E) \) is fully integral.)

One feels a kinship between Mazur’s formal immersion argument and Chabauty’s method, especially Coleman’s explicit version via \( p \)-adic integration [e29]. Indeed, Mazur’s argument has been translated into Coleman’s language by Baker [e50].

Mazur proved the isogeny theorem for elliptic curves with nonintegral (away from 2) \( j \)-invariant by different means, without any use of \( J_0(N) \). But the prime torsion theorem is easy in that case: Hasse’s theorem implies that an elliptic curve with a torsion point of order \( N \) with potentially good reduction at \( p \) satisfies \( N < (1+p^{1/2})^2 \), which implies \( N < 8 \) for \( p=3 \). To obtain the isogeny theorem, purely local arguments such as those do not suffice to supplement the integrality statement for \( j(E) \). But they constrain \( N \) so much that either \( N=13 \) or \( {\mathbf Q}(\sqrt{-N}) \) has class number 1 or \( N=37 \). The Heegner–Baker–Stark theorem imposes that \( N\le 163 \) [e17], [e12].

The proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem, by Wiles and Taylor–Wiles [e42], [e43], relied crucially on the torsion theorem. Indeed, a hypothetical solution to Fermat’s theorem, say \( a^N+b^N=c^N \), gives rise to the Frey–Hellegouarch elliptic curve given by \( y^2=x(x-a^N)(x+b^N) \), which in turn produces a newform of weight 2, level 2, modulo \( N \). Such a form is a cusp form, and therefore does not exist, provided the representation of the absolute Galois group on the \( N \)-division point on the Frey–Hellegouarch curve is irreducible, i.e., the curve does not admit a rational isogeny of degree \( N \). Because of the semistability of the curve, the full strength of Mazur’s isogeny theorem is not required, but there is no known substitute to the torsion theorem to rule out the reducibility.

In [5], Mazur asked whether there exist two elliptic curves \( E \), \( E^{\prime} \) over \( {\mathbf Q} \), non isogenous over \( {\mathbf Q} \), and a prime number \( N\ge 7 \) such that \( E[N] \) and \( E^{\prime}[N] \) are isomorphic as Galois modules. The question was given a positive answer by Kraus and Oesterlé [e38]. It developed into what is commonly called the Frey–Mazur conjecture: Fix \( E \), does there exist \( N_{E} \) such that the answer negative for \( N\ge N_{E} \)? Here is a more ambitious request: Does there exist \( N_{0} \) such that the answer is always negative for \( N\ge N_{0} \)? See [e32] for the considerable consequences for variants of Fermat’s Last Theorem, and beyond.

6. Program B, Question C and subsequent developments

The question seems as open in 2023 as it was in 1996. Program B precedes Question C in [3], was repeated verbatim in opening sentence of [4] and resonates with Serre’s uniformity question (see above [e19]).

Innumerable works on the torsion points of elliptic curves, and their Galois-theoretic properties have appeared in the 20th and 21st centuries. Most of them have been written after the Eisenstein ideal paper. Many have examined specific modular curves over specific number fields, have involved ingenious ideas and computer calculations. During the week September 18 to September 22 2023, two simultaneous conferences, one in Zagreb, one in Bangalore, were devoted mostly to this topic, and chiefly to Mazur’s Program B [3].

The progress belongs to two general directions which were already recognized around 1970: \( {\mathbf Q} \)-rational points of other modular curves and algebraic points of \( X_{1}(N) \).

For \( K={\mathbf Q} \), a positive answer to Serre’s problem amounts to show that three families of modular curves have no non-CM, noncuspidal \( {\mathbf Q} \)-rational points when their prime level is large enough. The three families are \( X_0(N) \), \( X_{\mathrm{split}}^+(N) \) and \( X_{\mathrm{nonsplit}}^+(N) \). The curve \( X_0(N) \) have been treated by Mazur in [5]. After additional work of Momose [e28], Parent [e56], and Rebolledo [e57], a breakthrough happened in 2008 when Bilu and Parent proved that the curve \( X_{\mathrm{split}}^+(N) \) has no non-CM, non cuspidal rational point for \( N \) large enough [e60] (it was established later for all \( N > 13 \) with the help of Rebolledo [e61]). These authors followed Mazur’s method to treat elliptic curves with non integral \( j \)-invariant. They introduced two new arguments to study elliptic curves with integral \( j \)-invariant. Their first argument was borrowed from transcendental number theory, in particular the successive refinements of the isogeny theorems of Masser–Wüstholz [e34]. Those refinement, due to David [e44], Pellarin [e53], and Gaudron–Rémond [e62], provided a lower bound (in term of \( N \)) for the logarithm of the \( j \)-invariant. The other original argument of Bilu and Parent is an adaptation of Runge’s method for integral points on curves. It provides an upper bound (in term of \( N \)) for the logarithm of the \( j \)-invariant, which contradicts the lower bound obtained by transcendence methods when \( N \) is large enough.

Thus, the non-CM, noncuspidal rational points of \( X_{\mathrm{split}}^+(N) \) for all prime numbers \( N \) could be determined, except for \( N=13 \). This particular level escaped Mazur’s approach, as the jacobian of \( X_{\mathrm{split}}^+(13) \) does not possess a nonzero quotient with finitely many rational points. The absence of any nontrivial rank 0 quotient is the key aspect of the jacobians of \( X_{\mathrm{nonsplit}}^+(N) \) which prevents the study the rational points of \( X_{\mathrm{nonsplit}}^+(N) \) by Mazur’s method. Indeed, even the amended version of Chabauty’s condition fails, as no quotient of the jacobian satisfies \( r < d \). Despite this inauspicious situation, the inexistence of non-CM, noncuspidal rational points on \( X_{\mathrm{split}}^+(13) \) and \( X_{\mathrm{nonsplit}}^+(13) \) has been established by way of involved and promising techniques, adapted from Kim’s generalization of Chabauty’s methods, especially when \( r=g \), by Balakrishnan, Dogra, Müller, Tuitman and Vonk [e64]. One would hope that history repeats itself, and that the breakthrough at level 13 would be followed by a general result. However, contra Mazur and Tate for \( X_{1}(13) \), [e64] relies on handling specific models of those modular curves of genus 3. Further efforts along those general lines [e69] so far do not provide yet complete lists of points on \( X_{\mathrm{nonsplit}}^+(N) \), which is the main problem left for \( K=\mathbf{Q} \).

Suppose now that \( K \) is any number field. Cassels’ “folklore conjecture”, often called the uniform boundedness conjecture, amounts to the inexistence of noncuspidal \( K \)-rational point on \( X_1(N) \) when \( N \) is large enough (depending on \( K \) only). The strengthening suggested by Shafarevich, accordingly called the strong uniform boundedness conjecture, would make the ‘large enough” depend on \( d=[K:{\mathbf Q}] \), asserting thus the nonexistence of noncuspidal \( {\mathbf Q} \)-rational points on the \( d \)-th symmetric power \( X_1(N)^{(d)} \) of \( X_1(N) \) for \( N \) large enough.

Kamienny extended Mazur’s approach explained above in the following manner. Consider the map \( \phi_d \): \( X_0(N)^{(d)}\rightarrow A \) obtained by composing the canonical maps \( X_0(N)^{(d)}\rightarrow J_0(N) \) and \( J_0(N)\rightarrow A \). It can be extended to a morphism \( \hat{\phi}_{d} \): \( {\mathcal X}^{(d)}\rightarrow {\mathcal A} \). Mazur’s argument in the isogeny theorem applies without much modification provided \( \hat{\phi}_d \) is a formal immersion in some characteristic \( p \), for \( p \) prime \( p > 2 \). Generalizing Mazur’s criterion for \( d=1 \), Kamienny showed that the latter condition is satisfied when the first \( d \) Hecke operators are \( {\mathbf F}_p \)-linearly independent as endomorphisms of \( \tilde A \). When \( A=\tilde J \), this means linear independence in \( {\mathbf T}/(p{\mathbf T}+I) \), where \( I \) is the kernel of \( {\mathbf T}\rightarrow{\mathbf T}_{\mathcal I} \) [e39]. Kamienny proved this to be satisfied when \( d=2 \) and \( N > 71 \) [e40] and then, with Mazur, when \( 2 < d\le 8 \), for \( N \) large enough [9]. Abramovich introduced a variant of this argument and showed that, when \( d\le 14 \), \( X_1(N)^{(d)} \) has noncuspidal rational points for only finitely many values of \( N \) [e41]. As for an analogue of the torsion theorem for quadratic fields, Kamienny determined a complete list of the prime numbers that could divide the order of torsion subgroups of elliptic curves over quadratic fields. The list of possible torsion subgroups for quadratic fields could be obtained with the help of Kenku and Momose [e31].

All this was still based on \( A=\tilde J \) and the finiteness of \( {\tilde J}({\mathbf Q}) \). One hardly imagines how Mazur could have devised the winding homomorphism in [4] without being aware that the finiteness of \( {\tilde J}({\mathbf Q}) \) follows from the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture. However, the latter conjecture was terra incognita in 1977.

Consider the maximal quotient \( J_e \) (the winding quotient, following the term introduced by Mazur and Swinnerton-Dyer) of \( J_0(N) \) whose \( L \)-function does not vanish at 1. By 1994, it followed from the work of Gross–Zagier [e30] and Kolyvagin [e33] complemented by important nonvanishing results due to Bump–Friedberg–Hoffstein [e36] and Murty–Murty [e37] that \( J_e({\mathbf Q}) \) is finite. In \( J_{e} \), a more general replacement for the Eisenstein quotient has emerged [e45]. The approach of Kamienny–Mazur applies with \( \tilde J \) replaced by \( J_{e} \) and, mutatis mutandis, given any \( d \), the required linear independence has been established for \( N \) large enough, proving thus the strong uniform boundedness conjecture [e45]. The method has been improved by Oesterlé and Parent [e51] and others to progress within Program B. For example, Derickx, Etropolski, van Hoeij, Morrow and Zureick-Brown [e70] listed completely the possible torsion subgroups of elliptic curves over cubic fields.

Despite occasional ulterior occurrences [e68], the Eisenstein quotient ceased thus to be an indispensable tool for further study of diophantine questions.

7. The Eisenstein line and the concept of fusion

Gauss’ pronouncement that not all number theory is diophantine finds an echo in the fact that the Eisenstein ideal is, more than ever, an invaluable concept for algebraic number theory. One might see in Ramanujan’s famous congruence between \( \Delta \) and \( E_{12} \) modulo 691, which predates by far Mazur’s work, an early manifestation of this notion. It is beyond the scope of this account to review all subsequent developments (e.g., the proofs of the converse Herbrand theorem by Ribet [e22] and of Iwasawa’s main conjecture by Mazur and Wiles [7]).

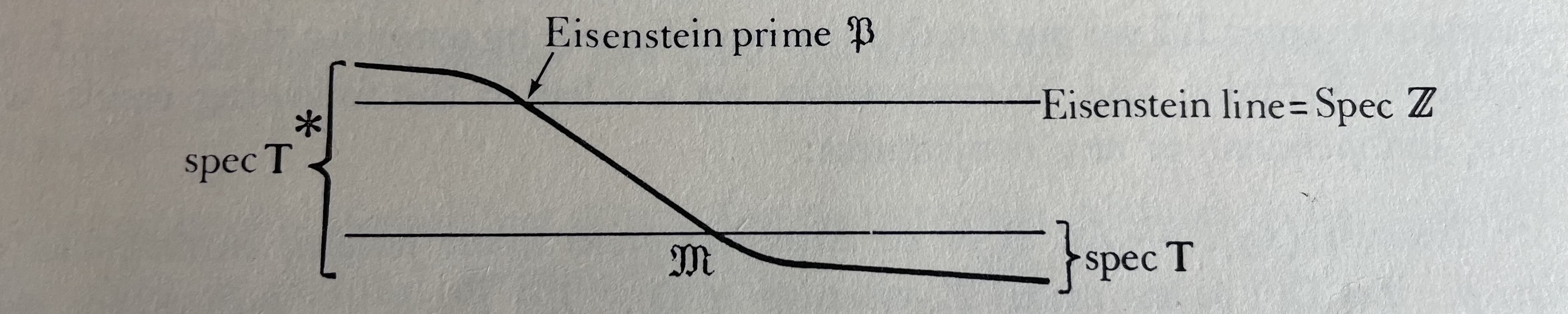

Mazur introduced vividly the Eisenstein quotient by a scheme-theoretic picture [4]:

He seems to be first to have examined \( {\mathbf T} \), or rather \( \operatorname{Spec}{\mathbf T} \), with the eye of a geometer. The geometric view of the Hecke algebra foreshadowed the eigencurve introduced in 1996 by Coleman and Mazur [10]. Already in [4], Mazur found it worthwhile to prove that \( \operatorname{Spec}{\mathbf T} \) is connected, even if it is useless for the torsion theorem.

To accomplish the Eisenstein descent, it was important to establish that the completion of \( {\mathbf T} \) at a maximal ideal \( {\mathcal M} \) is a Gorenstein ring, whenever \( \mathcal M \) is either of odd residual characteristic or Eisenstein. (Instances of failure of the Gorenstein property were found by Kilford in characteristic 2 [e54], and theoretically justified by Kilford and Wiese [e58].) This can be reformulated as a “multiplicity two theorem”: the \( {\mathcal M} \)-adic Tate module of \( J_{0}(N) \) is free of rank 2 over \( {\mathbf T}_{\mathcal M} \). Subsequently, the Gorenstein property was proved for other Hecke algebras [8], with the purpose of understanding Serre’s conjecture. It played an important part to prove many modularity theorems [e35], [e42], [e43], [e48]. An addendum by Mazur to the original proof can be found in [e49].

Whereas newforms and Galois representations used to be thought with coefficients in (completed) algebraic number fields, or their rings of integers, Mazur brought to the fore the usefulness and the necessity to allow coefficients in Hecke rings, whose subtleties, consequently, need to be studied.

Indeed, further down in the introduction of [4], one finds this prophetic gem:

One may think of the “geometric descent” argument […] as a technique of passing from the knowledge of the arithmetic of the Eisenstein line (i.e., of Eisenstein series, and of \( {\mathbf G}_{\mathrm{m}} \)) to the knowledge of the arithmetic of irreducible components meeting the Eisenstein line (i.e., of \( \tilde J \)) by a “descent” performed at a common prime ideal. One might hope that for other prime ideals common to distinct irreducible components (primes of fusion) one might make analogous passages […].

Under all appearances, Mazur had here in mind the question of understanding Selmer groups. However the philosophy of propagation along the connected components of \( \operatorname{Spec}{\mathbf T} \) was destined to become a central idea for automorphic forms, in particular for many modularity theorems obtained so far in the Langlands program.

Mazur gave an application of the principle of propagation in a subsequent work: If a newform \( f \) corresponds to an irreducible line that meets the Eisenstein line, the \( L \)-value of \( f \) at 1 is in agreement with the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer formula (and various twisted formulas) for this modular form at this Eisenstein prime [6]. This line of inquiry was pursued further by Stevens [e26].

In a similar vein, Cremona and Mazur have shown that fusion between two cusp forms (especially of unequal Mordell–Weil ranks) produces certain elements in Tate–Shafarevich groups, that they call visible [12]. If one of the modular forms is attached to an elliptic curve \( E \) over \( {\mathbf Q} \), an examination of a large set of examples indicates that the Tate–Shafarevich group of \( E \) is surprisingly often made of visible elements.

The Eisenstein ideal theory makes a crucial appearance in the conjectures of Harris and Venkatesh concerning modular forms of weight 1 [e65]. Let \( f \) be a new form of weight 1 for \( \Gamma_1(M) \), for \( M \) integer prime to \( N \). Harris and Venkatesh consider the modular form \[ F_N(z)=\operatorname{Tr}^{\Gamma_1(M)\cap\Gamma_0(N)}_{\Gamma_0(N)}(f(z)f(Nz)), \] which is a cusp form of weight 2 for \( \Gamma_0(N) \). The monodromy of the Shimura covering \( X_1(N)\rightarrow X_0(N) \) applied to \( F_N \) produces an element of \( ({\mathbf Z}/N{\mathbf Z})^{\times}/\mu_{12} \) (which identifies to the Galois group of the maximal unramified covering intermediate to the Shimura covering). This element is a pseudoeigenvalue of what Venkatesh calls the derived Hecke operator at \( N \) applied to \( f \), as one of the first interesting special cases of his general theory. In concrete terms, Harris and Venkatesh project \( F_N \) on the Eisenstein eigenspace and the pseudoeigenvalue turns out to be the coefficient of proportionality of \( F_N \) with the Eisenstein series.

8. The dual quest to understand the Eisenstein completion of \( {\mathbf T} \)

Despite all of Mazur’s efforts, the Eisenstein ideal still holds intrinsic mysteries. The ring \( {\mathbf T}_{\mathcal I} \) is isomorphic to \( \prod_{p|n}{\mathbf T}_{\mathcal P} \), where \( {\mathcal P}=p{\mathbf T}+{\mathcal I} \) is the maximal ideal of residual characteristic \( p \) in the support of the Eisenstein ideal. For \( p \) Eisenstein prime number, Mazur asked about the value \( r_p \) of the rank of \( {\mathbf T}_{\mathcal P} \) over \( {\mathbf Z}_{p} \) (see [4], page 140; and also What is this element \( u \)?, page 103). The investigation of this problem has followed two distinct lines of inquiry, which led to answers of a different nature that can fruitfully be compared. This situation recalls the classical dualism between the “algebraic” and “analytic” sides for the special values of \( L \)-functions.

Assume that \( p \) is not one of the unruly primes 2 and 3. Whenever \( r_p \) has small value can be expressed in terms of values modulo \( N \) of certain analogues of the zeta function and its derivatives (hence “analytic”). In concrete terms, \( r_p \) is \( > 1 \) if and only if \( \prod_{k=1}^{(N-1)/2}k^k \) is a \( p \)-th power modulo \( N \) or, alternately, in terms of supersingular elliptic curves, if and only if the discriminant of the Hasse polynomial in characteristic \( N \) is a \( p \)-th power) [e47], [e67].

Lecouturier introduced a higher Eisenstein theory to further study \( r_p \) and gave various elementary criteria for \( r_p > 2 \) [e67]. The most interesting development on the “analytic side” involved Sharifi’s conjectures, and their variants. The latter conjectures relate \( p \)-adic modular symbols to the second \( K \)-group of the cyclotomic ring \( {\mathbf Z}[\mu_N,1/Np] \) [e59]. Lecouturier and Wang deduced an isomorphism (explicitly expressed in terms of Steinberg symbols) between \( {\mathcal I}^2/{\mathcal I}^3\otimes \mathbf{Z}_p \) and \( JK_2({\mathbf Z}[\mu_N,1/Np])/J^2K_2({\mathbf Z}[\mu_N,1/Np])\otimes\mathbf{Z}_p \), where \( J \) is the augmentation ideal of \( {\mathbf Z}[\operatorname{Gal}({\mathbf Q}(\mu_N)/{\mathbf Q})] \), which acts on \( K_2({\mathbf Z}[\mu_N,1/Np]) \) [e71]. They derived conditional criteria for \( r_p > 3 \). It seems that Sharifi and Venkatesh have gone a long way to prove Sharifi’s conjecture. But no criterion for \( r_p > 4 \) has been given on the analytic side so far.

On the “algebraic side”, Calegari and Emerton adopted a different perspective [e55]. They defined and studied a ring from the theory of deformation of (two-dimensional, reducible) Galois representations without invoking modular forms. By way of an \( R=T \) theorem, they proved that the ring they have introduced is isomorphic to \( {\mathbf T}_{\mathcal I} \). They recovered directly the properties established by Mazur: structure of \( {\mathbf T}/{\mathcal I} \), of \( {\mathcal I}/{\mathcal I}^2 \). To illustrate the relevance to algebraic number theory, Calegari and Emerton have shown that \( r_p > 1 \) if the \( p \)-rank of the class group of \( {\mathbf Q}(N^{1/p}) \) is \( > 1 \), which, in turn, could be compared to the analytic criterion above. Wake and Wang-Erickson, with a different approach of deformation theory, and a different \( R=T \) theorem, proceeded further, and expressed \( r_p \) purely in terms of Galois cohomology using Massey products [e66]. About the analogy between relating the dual approaches of \( r_p \) to a conjecture about \( L \)-values, they asked:

[Wake and Wang-Erickson’s theorem relates \( r_p \)] to an “algebraic side” (vanishing of Massey products). It is natural to ask whether there is a corresponding object on the analytic side — is there a zeta element \( \tilde\zeta \) such that \( \operatorname{ord}(\tilde\zeta)=r_p \)?

Loïc Merel has been professor at Université Paris Cité and attached to the Institut de Mathématiques de Jussieu-Paris Rive Gauche since 1997.