by Cécile Armana, Sheng-Yang Kevin Ho and Mihran Papikian

1. Introduction

In the early 1970s, Andrew Ogg made several conjectures about the rational torsion points of elliptic curves over \( \mathbb{Q} \) and the Jacobians of modular curves; see [1], [2], [3]. In particular, he proposed a finite list of groups that can occur as rational torsion subgroups of elliptic curves over \( \mathbb{Q} \). These conjectures were proved shortly after by Barry Mazur [e13], [e14] as a consequence of his fundamental study of the arithmetic properties of modular curves and Hecke algebras. The powerful techniques introduced by Mazur had tremendous impact on later developments in arithmetic geometry; for example, they have been instrumental in the proof of the main conjecture of Iwasawa theory [e22] and the proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem [e37], [e38], [e30].

At around the same time, Vladimir Drinfeld [e10] introduced certain function field analogues of elliptic curves, which he called elliptic modules, nowadays known as Drinfeld modules. Drinfeld’s motivation was to construct function field analogues of classical modular curves classifying elliptic curves with some additional data, and to use these to relate automorphic forms and Galois representations, in line with the program envisioned by Langlands. The theory of Drinfeld modules and their generalizations, called shtukas, has since lead to a successful resolution of the Langlands correspondence over function fields (see [e15], [e35], [e57], [e93]), and it continues to play a central role in number theory because of its applications to many other important problems, such as the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture; see [e91].

Due to the close similarity between elliptic curves and Drinfeld modules, Ogg conjectures have natural analogues in the function field setting, as was already suggested by Mazur in [e13]. As in the classical case, a comprehensive approach to these conjectures relies heavily on the theory of (Drinfeld) modular forms and modular varieties. Since some of the necessary aspects of this theory were developed only in the 1990s, the analogues of Ogg’s conjectures were stated and proved in certain cases only in the 2000s; see [e58], [e66], [e78].

In this paper, we review the function field analogues of Ogg’s conjectures, their current status, and the methods that have been applied to prove some of these conjectures. The methods are based on the ideas of Mazur and Ogg, but there are interesting differences and technical complications that arise in the function field setting, as well as intriguing possible new directions for generalizations.

The contents of the paper are as follows. In Section 2, we recall the statements of Ogg’s original conjectures, some of their generalizations, and what is currently known about these conjectures (Ogg’s conjectures have been generalized in many different directions, and our exposition of these generalizations is by no means exhaustive). In Section 3, we review the basic theory of Drinfeld modules, putting the emphasis on those aspects of the theory that are relevant for Ogg’s conjectures. In Section 4, we review the theory of Drinfeld modular forms, which is extensively used in the proofs of the analogues of Ogg’s conjectures. In Sections 5 and 6, we give the statements of Ogg’s conjectures in the setting of Drinfeld’s theory, the current status of these conjectures, a brief summary of the ideas that go into the proofs, and some of the nontrivial complications that arise in this setting.

2. Ogg’s conjectures

2.1. Torsion of elliptic curves

The first, and probably most famous, conjecture in Ogg’s paper [3] gives a classification of possible torsion subgroups \( E(\mathbb{Q})_\mathrm{tor} \) of elliptic curves over \( \mathbb{Q} \). This conjecture was essentially formulated by Beppo Levi in 1908, although Ogg was not aware of this as Levi’s work on the arithmetic of elliptic curves did not receive the attention it deserved. In any case, Ogg’s papers were instrumental in spelling out the close connection between this problem and the theory of modular curves and in popularizing the conjecture.

A related conjecture, stated in [3] as a problem, concerns rational cyclic subgroups of elliptic curves over \( \mathbb{Q} \). If \( C \) is a finite subgroup of an elliptic curve \( E \) over \( \mathbb{Q} \), then \( C \) is said to be rational if \( \sigma(C)=C \) for all \( \sigma\in \operatorname{Gal}(\overline{\mathbb{Q}}/\mathbb{Q}) \).

The philosophy behind Conjectures TEC and TEC\( ^+ \) is that “modular curves only have rational points for which there is a

reason”, the reason being geometric

([3],

p. 17).

More specifically, \( Y_1(N) \) has a \( \mathbb{Q} \)-rational point if and only if \( X_1(N) \) has genus 0. The

genus of \( X_1(N) \) is 0 exactly for \( 1\leq N\leq 10 \) and \( N=12 \). Moreover, for

these values \( X_1(N) \) has infinitely many \( \mathbb{Q} \)-rational points, so the groups

listed in Conjectures TEC occur as the rational torsion subgroups of infinitely many nonisomorphic elliptic curves over \( \mathbb{Q} \).

Similarly, \( X_0(N)(\mathbb{Q}) \) is infinite if and only if its genus is 0, which happens exactly

for \( 1\leq N\leq 10 \) and \( N=12,13,16,18,25 \). The curve \( X_0(N) \) has genus 1, and \( Y_0(N)(\mathbb{Q}) \)

is finite and known for \( N=11,14,15,17,19,21,27 \). The cases when \( X_0(N) \) has genus \( \geq 2 \) and

\( Y_0(N)(\mathbb{Q}) \) is nonempty are \( N=37, 43, 67, 163 \).

For \( N=43, 67, 163 \), the curve \( Y_0(N) \) has one \( \mathbb{Q} \)-rational point which

corresponds to an elliptic curve over \( \mathbb{Q} \) with CM by the ring of integers of

\( \mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{-N}) \) (note that in these cases the class number of \( \mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{-N}) \) is

one). The case \( N=37 \) is somewhat special: \( Y_0(37) \) has two \( \mathbb{Q} \)-rational

points, whose existence is related to the fact that the hyperelliptic involution

of \( X_0(37) \) is not the Atkin–Lehner involution.

Conjectures TEC and TEC\( ^+ \) were proved by Mazur in [e13], [e14], where he developed an intricate arithmetic theory of modular curves, Eisenstein ideals in Hecke algebras, and isogeny characters of elliptic curves.

By extending Mazur’s techniques, one can attack the problem of classifying the points on \( X_1(N) \) and \( X_0(N) \) that are rational over number fields of given degree; see [e34], [e108]. One can also consider rational points on Shimura curves classifying abelian surfaces with quaternionic multiplication; see [e25], [e82].

The Uniform Boundedness Conjecture (UBC) extends Conjecture TEC to all number fields, but without giving an explicit classification. This conjecture is mentioned in [3] as a “folklore conjecture”.

The UBC was proved by Merel [e45], again building upon Mazur’s work and subsequent refinements by Kamienny, and combining them with the progress, recent at the time, on the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture.

Finally, one can extend Conjectures TEC and TEC\( ^+ \) to modular curves classifying elliptic curves with other level structures, such as split or nonsplit Cartan subgroups. These conjectures are closely related to Serre’s Uniformity Question (SUQ):

Although the SUQ remains open, substantial progress has been made: it is known that for \( p > 37 \) the representation \( \rho_{E, p} \) is either surjective or its image is contained in the normalizer of a nonsplit Cartan subgroup; see [e73], [e79], [e95].

2.2. Torsion of the Jacobian variety of \( X_0(N) \)

When \( N=p \) is prime, there are only two cusps on \( X_0(p) \), usually denoted by \( [0] \) and \( [\infty] \). In [2], Ogg computed that the divisor class of \( [0]-[\infty] \) in \( J_0(p) \) has order \[ n=(p-1)/\gcd(p-1, 12). \] Both cusps are rational, so \( \mathcal{C}(p)=\mathcal{C}_p(\mathbb{Q})=\mathcal{C}_p \). Based on numerical experimentations [3], Ogg conjectured the following.

Mazur proved this conjecture in [e13] using his theory of the Eisenstein ideal of the Hecke algebra of level \( p \). There is a natural generalization of this conjecture to arbitrary \( N \), nowadays called the generalized Ogg conjecture.

Note that Conjecture CJ-N is a combination of two conjectures. The first is the equality \( \mathcal{C}(N)=\mathcal{C}_N(\mathbb{Q}) \), which concerns only the cuspidal divisor group; this was explicitly conjectured by Hwajong Yoo in [e107] in response to a question of Ribet. The second is the equality \( \mathcal{C}_N(\mathbb{Q})=J_0(N)(\mathbb{Q})_\mathrm{tor} \), which predicts that all \( \mathbb{Q} \)-rational torsion points on \( J_0(N) \) arise from cuspidal divisors, so there are no “unexpected” \( \mathbb{Q} \)-rational torsion points on \( J_0(N) \).

Determining the structure of the cuspidal divisor group for general \( N \) is quite complicated. Recently, Yoo [e107] was able to determine the structure of \( \mathcal{C}(N) \) completely by extending earlier work of Lorenzini, Ling, Takagi, and others. Yoo’s proof combines a careful study of modular units with explicit construction of appropriate rational cuspidal divisors. Consequently, if Conjecture CJ-N is true, then the structure of \( J_0(N)(\mathbb{Q})_\mathrm{tor} \) is determined as well.

The conjecture \( \mathcal{C}(N)=\mathcal{C}_N(\mathbb{Q}) \) is known in some cases, but not in general. Note that for square-free \( N \), we trivially have \( \mathcal{C}(N)=\mathcal{C}_N(\mathbb{Q})=\mathcal{C}_N \) because all the cusps are rational. The known nontrivial cases are essentially those \( N \) whose prime decomposition contains at most two prime factors with higher powers; the interested reader may consult the introduction of [e107] for a list of known cases.

Given a finite abelian group \( G \) and a prime \( \ell \), we denote by \( G_\ell \) the \( \ell \)-primary subgroup of \( G \). Note that the equality \begin{equation}\label{eqC=J} \mathcal{C}(N)_\ell = (J_0(N)(\mathbb{Q})_\mathrm{tor})_\ell \tag{2.1} \end{equation} implies \( \mathcal{C}(N)_\ell=\mathcal{C}_N(\mathbb{Q})_\ell \). The strongest result towards the equality \eqref{eqC=J} is the following recent result of Yoo [e110].

Yoo’s proof is based on the theory of Eisenstein ideals, with important refinements introduced by Ohta in [e83], where Theorem 2.1 is proved for square-free \( N \).

(2) The proofs of special cases of Conjecture CJ-N by Lorenzini, Mazur, Ohta, and Yoo implicitly rely on the knowledge of the order of \( \mathcal{C}(N) \). In [e105], Ribet and Wake prove the equality \eqref{eqC=J} for square-free \( N \) and \( \ell\nmid 6N \) by showing that both sides are isomorphic modules for the Hecke algebra acting on \( J_0(N) \), without actually computing either side explicitly.

(3) The methods used so far to prove \eqref{eqC=J} in certain cases fall short of proving this equality for \( \ell=2 \). Thus, \eqref{eqC=J} remains largely open for the 2-primary part, except when \( N=p \) is prime. We note that the most technical arguments in Mazur’s paper [e13] proving Conjecture CJ-p are actually concerned with the 2-primary torsion.

(4) In [e81], Ohta proves that \( (J_1(p)(\mathbb{Q})_\mathrm{tor})_\ell \) is generated by cuspidal divisors for any odd prime \( \ell \), as was conjectured by Conrad, Edixhoven and Stein [e60]. The proof again relies on the Eisenstein ideal machinery.

Conjecture CJ-p has a “dual” version concerning the largest \( \mu \)-type subgroup \( \mathcal{M}(N) \) of \( J_0(N) \); a commutative group scheme is \( \mu \)-type if it is finite, flat, and its Cartier dual is a constant group scheme. The natural morphism \( X_1(N)\to X_0(N) \) induces, by Picard functoriality, a morphism of their Jacobians \( J_0(N)\to J_1(N) \). The kernel of this last morphism is called the Shimura subgroup of \( J_0(N) \), and will be denoted by \( \mathcal{S}(N) \).

When \( N=p \) is prime, \( \mathcal{S}(p) \) is cyclic of the same order as

\( \mathcal{C}(p) \). In [3],

Ogg conjectured:

This conjecture was proved by Mazur in [e13]. Despite the dual appearance of Conjectures CJ-p and SJ-p, the proof of Conjecture SJ-p lies deeper than the proof of Conjecture CJ-p since its proof relies on the fact that the completion of the Hecke algebra at any prime ideal in the support of Eisenstein ideal is Gorenstein. For general \( N \), the order of \( \mathcal{S}(N) \), the action of the Hecke operators and the action of \( \operatorname{Gal}(\overline{\mathbb{Q}}/\mathbb{Q}) \) on \( \mathcal{S}(N) \) are computed in [e33]. In particular, \( \mathcal{S}(N)\subseteq \mathcal{M}(N) \). The following generalization of Mazur’s result was proved by Vatsal [e65].

Vatsal’s proof is very different from Mazur’s. It combines a theorem of Ihara about unramified coverings of modular curves over finite fields with some deep results about the supersingular reductions of CM points on \( X_0(N) \) and special values of \( L \)-functions.

3. Review of Drinfeld modules

3.1. Analytic theory

First, we introduce the analogues of real and complex numbers in the function field setting. The degree function \( \deg=\deg_T\colon A\to \mathbb{Z}_{\geq 0}\cup \{-\infty\} \), which assigns to \( 0\neq a\in A \) its degree as a polynomial in \( T \) and \( \deg_T(0)=-\infty \), extends to \( F \) by \( \deg(a/b)=\deg(a)-\deg(b) \). The map \( -\deg \) is a valuation on \( F \); the corresponding place of \( F \) is usually denoted by \( \infty \). Let \( \lvert\,\cdot\,\rvert \) denote the corresponding absolute value on \( F \) normalized by \( \lvert T \rvert=q \). The completion \( F_\infty \) of \( F \) with respect to this absolute value is isomorphic to the field \( \mathbb{F}_q(\!({1/T})\!) \) of Laurent series in \( 1/T \). Finally, let \( \mathbb{C}_\infty \) be the completion of an algebraic closure of \( F_\infty \). The absolute value \( \lvert\,\cdot\,\rvert \) has a unique extension, also denoted by \( \lvert\,\cdot\,\rvert \), to \( \mathbb{C}_\infty \).

An \( A \)-lattice \( \Lambda\subset \mathbb{C}_\infty \) of rank \( r\geq 1 \) is a discrete \( A \)-submodule of \( \mathbb{C}_\infty \) of rank \( r \), where “discrete” means that for any \( N > 0 \) the set \( \{\lambda\in \Lambda: \lvert\lambda\rvert\leq N\} \) is finite. One shows that any \( A \)-lattice is of the form \( \Lambda=A\omega_1+\cdots +A\omega_r \), where \( \omega_1, \dots, \omega_r\in \mathbb{C}_\infty \) are linearly independent over \( F_\infty \). Since the degree of \( \mathbb{C}_\infty \) over \( F_\infty \) is infinite, there are \( A \)-lattices of arbitrarily large ranks (unlike \( \mathbb{Z} \)-lattices in \( \mathbb{C} \)).

The exponential function of \( \Lambda \) is

\[

e_\Lambda(x)=x\prod_{0\neq \lambda\in \Lambda} \left(1-\frac{x}{\lambda}\right).

\]

Using the discreteness of \( \Lambda \), it is not hard to show that the function

\( e_\Lambda(x) \) is entire, i.e., converges everywhere on \( \mathbb{C}_\infty \). Because

of the nonarchimedean setting, this implies that \( e_\Lambda(x)\colon

\mathbb{C}_\infty\to \mathbb{C}_\infty \) is surjective.

The set of zeros of \( e_\Lambda \) is exactly \( \Lambda \).

Finally, because \( \Lambda \) is an \( \mathbb{F}_q \)-vector space, \( e_\Lambda(x) \) satisfies \( e_\Lambda(x+y)=e_\Lambda(x)+e_\Lambda(y) \) and \( e_\Lambda(\alpha x)=\alpha e_\Lambda(x) \) for all

\( \alpha\in \mathbb{F}_q \). In other words, \( e_\Lambda(x) \) is an \( \mathbb{F}_q \)-linear function. Thus, the power series expansion of \( e_\Lambda(x) \) is of the form

\[

e_\Lambda(x)=\sum_{n\geq 0} e_n(\Lambda)x^{q^n}.

\]

There are recursive formulas for the coefficients of \( e_\Lambda \) in terms of Eisenstein series:

If we put

\begin{equation}\label{eqEisSer}

E_n(\Lambda)=\sum_{0\neq \lambda\in \Lambda}

\frac{1}{\lambda^n},\tag{3.1}

\end{equation}

then

\begin{equation}\label{eqCoefExp}

e_n(\Lambda) = E_{q^n-1}(\Lambda)+\sum_{i=1}^{n-1}e_i(\Lambda)

E_{q^{n-i}-1}(\Lambda)^{q^i}. \tag{3.2}

\end{equation}

Let

\[

\mathbb{C}_\infty\{x\}=\{a_0x+a_1x^q+\cdots+a_n x^{q^n}\mid n\geq 0,

a_0, \dots, a_n\in \mathbb{C}_\infty\}

\]

be the noncommutative ring

of \( \mathbb{F}_q \)-linear polynomials with usual addition of polynomials but where multiplication is defined via the composition of polynomials. For example,

\[

(Tx+x^q)\circ (x+Tx^{q^2})=T(x+Tx^{q^2})+(x+Tx^{q^2})^q= Tx+x^q+T^2x^{q^2}+T^qx^{q^3}.

\]

Given \( f(x)=a_0x+a_1x^q+\cdots+a_n x^{q^n} \) in \( \mathbb{C}_\infty\{x\} \),

we denote \( \partial f=\frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d} x}f(x)=a_0 \).

An important property of \( e_\Lambda(x) \) is the functional equation \[ e_\Lambda(T x) = \phi_T^\Lambda(e_\Lambda(x)), \] where \[ \phi_T^\Lambda(x)=Tx+g_1(\Lambda)x^q+\cdots+ g_r(\Lambda)x^{q^r}\in \mathbb{C}_\infty\{x\},\quad g_r(\Lambda)\neq 0. \] Because \( e_\Lambda(x) \) is \( \mathbb{F}_q \)-linear, this functional equation extends to all \( a\in A \): for each \( a\in A \), there is \( \phi_a^\Lambda(x)\in \mathbb{C}_\infty\{x\} \) such that \( \deg_x \phi_a^\Lambda(x)=\lvert a \rvert^r \), \( \partial \phi_a^\Lambda=a \), and \( e_\Lambda(a x)= \phi_a^\Lambda(e_\Lambda(x)) \). Moreover, the map \begin{align*} \phi^\Lambda\colon A &\longrightarrow \mathbb{C}_\infty\{x\}, \\ a &\longmapsto \phi_a^\Lambda(x) \end{align*} is an \( \mathbb{F}_q \)-algebra homomorphism, called the Drinfeld module of rank \( r \) associated to \( \Lambda \).

Conversely, a Drinfeld \( A \)-module of rank \( r \) over \( \mathbb{C}_\infty \) is an \( \mathbb{F}_q \)-algebra homomorphism \( \phi\colon A\to \mathbb{C}_\infty\{x\} \), \( a\mapsto \phi_a(x) \), defined by \( \phi_T(x)=Tx+g_1x^q+\cdots +g_r x^{q^r} \) with \( g_r\neq 0 \). One constructs an entire \( \mathbb{F}_q \)-linear function \( e_\phi(x) \) satisfying \( e_\phi(Tx)=\phi_T(e_\phi(x)) \) as follows. Put \[ e_\phi(x) = e_0x+e_1x^q+e_2x^{q^2}+\cdots, \] where \( e_0, e_1, \dots \) are to be determined. The functional equation \( e_\phi(Tx)=\phi_T(e_\phi(x)) \) leads to a system of equations \[ (T^{q^n}-T)e_n=e_{n-1}^qg_1+e_{n-2}^{q^2}g_2+\cdots+ e_{n-r}^{q^r}g_r, \quad n\geq 0, \] where \( e_i=0 \) for \( i < 0 \). If we put \( e_0=1 \), then every other \( e_n \) is uniquely determined from the above recursive formulas. It is not hard to show that the resulting function \( e_\phi(x) \) is entire and the set of zeros \( \Lambda_\phi \) of \( e_\phi \) is an \( A \)-lattice of rank \( r \) such that \( \phi=\phi^{\Lambda_\phi} \).

A morphism \( u\colon \phi\to \psi \) of Drinfeld modules is a polynomial \( u(x)\in \mathbb{C}_\infty\{x\} \) such that \( u(\phi_a(x))=\psi_a(u(x)) \) for all \( a\in A \). A morphism \( u\colon \phi\to \psi \) is an isomorphism if \( u \) is invertible, i.e., \( u=c\in \mathbb{C}_\infty^\times \). Note that since \( T \) generates the \( \mathbb{F}_q \)-algebra \( A \), the commutation \begin{equation}\label{eq-defmor} u(\phi_T(x))=\psi_T(u(x))\tag{3.3} \end{equation} is sufficient to ensure \( u(\phi_a(x))=\psi_a(u(x)) \) for all \( a\in A \). Comparing the degrees of both sides of \eqref{eq-defmor}, we see that nonzero morphisms can exist only between Drinfeld modules of the same rank. We denote the set of all morphisms \( \phi\to \psi \) by \( \operatorname{Hom}(\phi, \psi) \). A morphism of lattices \( \Lambda\to \Lambda^{\prime} \) is an element \( c\in \mathbb{C}_\infty \) such that \( c\Lambda\subseteq \Lambda^{\prime} \). The set of all morphisms \( \Lambda\to \Lambda^{\prime} \) is denoted \( \operatorname{Hom}(\Lambda, \Lambda^{\prime}) \). Both \( \operatorname{Hom}(\phi, \psi) \) and \( \operatorname{Hom}(\Lambda, \Lambda^{\prime}) \) are naturally \( A \)-modules. One shows that there is an isomorphism of \( A \)-modules \begin{align*} \operatorname{Hom}(\phi, \psi) &\overset{\sim}{\longrightarrow} \operatorname{Hom}(\Lambda_\phi, \Lambda_\psi)\\ u &\longmapsto \partial u. \end{align*} From these constructions we get:

Given a Drinfeld module \( \phi \), we equip \( \mathbb{C}_\infty \) with a new \( A \)-module structure \( a\circ z =\phi_a(z) \) denoted \( {^\phi}\mathbb{C}_\infty \). This gives an exact sequence of \( A \)-modules \begin{equation}\label{eqDMUnif} 0\longrightarrow \Lambda_\phi \longrightarrow \mathbb{C}_\infty \overset{e_\phi}{\longrightarrow} {^{\phi}}\mathbb{C}_\infty\longrightarrow 0, \tag{3.5} \end{equation} which can be interpreted as the analogue of analytic uniformization \( \mathbb{C}/\Lambda\overset{\sim}{\longrightarrow}E(\mathbb{C}) \), \( z\mapsto (\wp(z), \wp^{\prime}(z)) \) of an elliptic curve \( E \) over \( \mathbb{C} \) (here \( \wp \) is the Weierstrass \( \wp \)-function associated to the lattice \( \Lambda \)).

For nonzero \( a\in A \), the \( a \)-torsion points of \( \phi \) are the roots of \( \phi_a(x) \). The set of these roots, denoted \( \phi[a] \), is naturally an \( A \)-module via \( b\circ \alpha = \phi_b(\alpha) \), where \( b\in A \) and \( \alpha\in \phi[a] \) (to see that \( b\circ \alpha \) is in \( \phi[a] \), compute \( \phi_a(b\circ \alpha)=\phi_a(\phi_b(\alpha))=\phi_b(\phi_a(\alpha))=\phi_b(0)=0 \)). Applying the snake lemma to the exact sequence \eqref{eqDMUnif}, we get an isomorphism of \( A \)-modules: \[ \phi[a]\cong \Lambda_\phi/a\Lambda_\phi\cong (A/aA)^r. \] A morphism \( u\colon \phi\to \psi \) induces a homomorphism \( {^\phi}\mathbb{C}_\infty\to {^\psi}\mathbb{C}_\infty \) of \( A \)-modules. In particular, \( u \) induces a homomorphism \( \phi[a]\to \psi[a] \), \( \alpha\mapsto u(\alpha) \).

It is easy to show that two Drinfeld modules \( \phi \) and \( \psi \) are isomorphic if and only if their corresponding lattices are homothetic: \( \Lambda_\phi= c\Lambda_\psi \) for \( c\in\mathbb{C}_\infty^\times \). Thus, to classify Drinfeld modules of rank \( r \) up to isomorphism, it is enough to classify \( A \)-lattices in \( \mathbb{C}_\infty \) of rank \( r \) up to homothety. This is trivial if \( r=1 \). For \( r\geq 2 \) the key object for our task is the Drinfeld symmetric space \[ \Omega^r= \mathbb{P}^{r-1}(\mathbb{C}_\infty)-\bigcup_{F_\infty\mathrm{-rational }\, H} H, \] where the union is over the \( F_\infty \)-rational hyperplanes; equivalently, \( \Omega^r \) is the set of all points \( (z_1, \dots, z_r) \) of \( \mathbb{P}^{r-1}(\mathbb{C}_\infty) \) such that \( z_1, \dots, z_r \) are linearly independent over \( F_\infty \). To the point \( (z_1, \dots, z_r) \) we associate the homothety class of the lattice \( Az_1+\cdots+Az_r \). The action of \( \mathrm{GL}_r(F_\infty) \) on \( \mathbb{P}^{r-1}(\mathbb{C}_\infty) \) preserves \( \Omega^r \).

From the bijection between lattices and Drinfeld modules, one deduces that the set of isomorphism classes of Drinfeld modules of rank \( r \) over \( \mathbb{C}_\infty \) is in natural bijection with the set of orbits \[ \mathrm{GL}_r(A)\setminus\Omega^r. \]

Each nonzero ideal \( \mathfrak{n}\lhd A \) has a unique monic generator, which, by abuse of notation, we will also denote by \( \mathfrak{n} \). Define the subgroups \( \Gamma(\mathfrak{n})\subseteq \Gamma_1(\mathfrak{n})\subseteq \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})\subseteq \mathrm{GL}_r(A) \) as \[ \Gamma(\mathfrak{n})=\left\{\gamma\in \mathrm{GL}_r(A)\mid \gamma\equiv 1 (\operatorname{mod} \mathfrak{n})\right\}, \] \[ \Gamma_1(\mathfrak{n})= \left\{\begin{pmatrix} c_{ij}\end{pmatrix}\in \mathrm{GL}_r(A)\mid \begin{pmatrix} c_{11}\\ c_{21}\\ \vdots\\ c_{r1} \end{pmatrix}\equiv \begin{pmatrix} 1\\ 0\\ \vdots\\ 0 \end{pmatrix} (\operatorname{mod}\mathfrak{n})\right\}, \] \[ \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})= \left\{\begin{pmatrix} c_{ij}\end{pmatrix}\in \mathrm{GL}_r(A)\mid \begin{pmatrix} c_{11}\\ c_{21}\\ \vdots\\ c_{r1} \end{pmatrix}\equiv \begin{pmatrix} \ast\\ 0\\ \vdots\\ 0 \end{pmatrix} (\operatorname{mod}\mathfrak{n})\right\}. \] Extending the above bijection, one shows that the orbits \( Y^r_0(\mathfrak{n})(\mathbb{C}_\infty):= \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})\setminus \Omega^r \) are in bijection with the isomorphism classes of pairs \( (\phi, G_\mathfrak{n}) \), where \( \phi \) is a Drinfeld module of rank \( r \) and \( G_\mathfrak{n}\subset \phi[\mathfrak{n}] \) is an \( A \)-submodule isomorphic to \( A/\mathfrak{n} \) (two pairs \( (\phi, G_\mathfrak{n}) \) and \( (\phi^{\prime}, G_\mathfrak{n}^{\prime}) \) are isomorphic if there is an isomorphism \( u\colon \phi\overset{\sim}{\to}\phi^{\prime} \) such that \( u(G_n)=G_n^{\prime} \)). Similarly, \[ Y^r_1(\mathfrak{n})(\mathbb{C}_\infty):=\Gamma_1(\mathfrak{n})\setminus \Omega^r \longleftrightarrow \{\text{isomorphism classes of pairs } (\phi, P_\mathfrak{n})\}, \] where \( \phi \) is a Drinfeld module of rank \( r \) and \( P_\mathfrak{n}\in \phi[\mathfrak{n}] \) is a torsion point which generates an \( A \)-submodule isomorphic to \( A/\mathfrak{n} \). Finally, \( Y^r(\mathfrak{n})(\mathbb{C}_\infty):=\Gamma(\mathfrak{n})\setminus \Omega^r \) classifies the isomorphism classes of pairs \( (\phi, \tilde{\iota}) \), where \( \tilde{\iota} \) is a choice of an \( A/\mathfrak{n} \)-basis of \( \phi[\mathfrak{n}] \) such that the Weil pairing ([e109], p. 298) on this basis takes a certain value in \( (A/\mathfrak{n})^\times/\mathbb{F}_q^\times \).

The quotients \( Y=Y^r(\mathfrak{n}), Y^r_1(\mathfrak{n}), Y^r_0(\mathfrak{n}) \) are much more than just sets. In [e10], Drinfeld showed that \( \Omega^r \) has a natural structure of a smooth rigid-analytic manifold over \( F_\infty \), and that the group \( \mathrm{GL}_r(A) \) acts discontinuously on \( \Omega^r \), so \( Y \) has a structure of an analytic manifold over \( F_\infty \). Moreover, he proved that \( Y \) is algebraizable, in the sense that it is the analytic space corresponding to an affine algebraic variety over \( F_\infty \). This point of view will be discussed at the end of Section 3.2. For more about analytic geometry over nonarchimedean fields, the reader might consult [e61].

3.2. Algebraic theory

Let \( K\{x\} \) be the noncommutative ring of \( \mathbb{F}_q \)-linear polynomials with coefficients in \( K \), defined as earlier for \( K=\mathbb{C}_\infty \). The ring \( K\{x\} \) can be identified with the ring of \( \mathbb{F}_q \)-linear endomorphisms of the additive group scheme \( \mathbb{G}_{a, K} \) over \( K \). A Drinfeld module of rank \( r\geq 1 \) over \( K \) is an \( \mathbb{F}_q \)-algebra homomorphism \( \phi\colon A \to K\{x\} \), \( a\mapsto \phi_a(x) \), such that \[ \phi_T(x)=tx+g_1x^q+\cdots+g_rx^{q^r}, \quad g_r\neq 0. \] Note that the homomorphism \( \phi \) is always injective, even if \( \operatorname{char}_A(K)\neq 0 \), so \( \phi \) gives an embedding of the commutative ring \( A \) into the noncommutative ring \( K\{x\} \). From the definition it follows that \( \partial \phi_a=\gamma(a) \) for all \( a\in A \). Hence, \( \phi \) equips \( \mathbb{G}_{a, K} \) with a new action of \( A \) such that on the tangent space of \( \mathbb{G}_{a, K} \) around the origin the induced action of \( A \) is via the structure morphism \( \gamma \).

Given a polynomial \( f(x)=a_0x+a_1x^q +\cdots+ a_dx^{q^d}\in K\{x\} \), the smallest index \( 0\leq h\leq d \) such that \( a_h\neq 0 \) is the height of \( f \), denoted \( \operatorname{ht}(f) \). If \( \operatorname{char}_A(K)=\mathfrak{p}\neq 0 \), then \( \gamma \) factors through the quotient \( A\to A/\mathfrak{p} \) and \( \operatorname{ht}(\phi_\mathfrak{p}) > 0 \). Using the commutation \( \phi_a(\phi_\mathfrak{p}(x))=\phi_\mathfrak{p}(\phi_a(x)) \), it is not hard to show that there is an integer \( 1\leq H(\phi)\leq r \), called the height of \( \phi \), such that for all nonzero \( a\in A \) we have \[ \operatorname{ht}(\phi_a)=H(\phi)\cdot \operatorname{ord}_\mathfrak{p}(a)\cdot \deg(\mathfrak{p}), \] where \( \operatorname{ord}_\mathfrak{p}(a) \) is the power with which \( \mathfrak{p} \) divides \( a \).

Given a Drinfeld module \( \phi \) over \( K \) of rank \( r \) and \( 0\neq a\in A \), let \( \phi[a] \) be the set of roots of \( \phi_a(x) \) in an algebraic closure \( \overline{K} \) of \( K \) without repetitions. As over \( \mathbb{C}_\infty \), the set \( \phi[a] \) is naturally an \( A \)-module. Decomposing \( a=\mathfrak{p}_1^{s_1}\cdots\mathfrak{p}_m^{s_m} \) into distinct prime powers, we get an isomorphism of \( A \)-modules \[ \phi[a]\cong \phi[\mathfrak{p}_1^{s_1}]\times \cdots \times \phi[\mathfrak{p}_m^{s_m}]. \] Moreover, for a prime \( \mathfrak{p} \) we have \[ \phi[\mathfrak{p}^n]\cong \begin{cases} (A/\mathfrak{p}^n)^r, & \text{if } \mathfrak{p}\neq \operatorname{char}_A(K); \\ (A/\mathfrak{p}^n)^{r-H(\phi)}, & \text{if } \mathfrak{p} = \operatorname{char}_A(K). \end{cases} \]

Assume that \( \operatorname{char}_A(K)\nmid a \). In this case the polynomial \( \phi_a(x)\in K[x] \) is separable, so the \( A \)-module \( \phi[a] \) is naturally equipped with an action of the absolute Galois group \( G_K:=\operatorname{Gal}(K^{\operatorname{sep}}/K) \) of \( K \). Since this action commutes with the action of \( A \), we obtain a representation \begin{equation}\label{eqResRep} \rho_{\phi, a}: G_K\longrightarrow \operatorname{Aut}_A(\phi[a])\cong \mathrm{GL}_r(A/aA). \tag{3.6} \end{equation}

Repeating an earlier definition, a morphism \( u\colon \phi\to \psi \) is an element \( u\in K\{x\} \) such that \( u\circ \phi_T=\psi_T\circ u \) (and thus, \( u\circ \phi_a=\psi_a\circ u \) for all \( a\in A \)). The set \( \operatorname{Hom}_K(\phi, \psi) \) of all morphisms \( \phi\to \psi \) is naturally an \( A \)-module, with the action of \( a\in A \) on \( u\in \operatorname{Hom}_K(\phi, \psi) \) defined by \( a * u=u\circ \phi_a=\psi_a\circ u \). A basic fact of the theory of Drinfeld modules is that if \( \phi \) and \( \psi \) have rank \( r \), then \( \operatorname{Hom}_K(\phi, \psi) \) is a free \( A \)-module of rank \( \leq r^2 \). Denote \( \operatorname{End}_K(\phi):=\operatorname{Hom}_K(\phi, \phi) \); this is the centralizer of \( \phi(A) \) in \( K\{x\} \).

The action of \( u\in \operatorname{End}_K(\phi) \) on \( \phi[a] \) commutes with the action of \( G_K \). If \( \mathfrak{p}\neq \operatorname{char}_A(\phi) \), then there is an injective homomorphism \[ \operatorname{End}_K(\phi)\otimes_A A/aA\longrightarrow \operatorname{End}_{A[G_K]}(\phi[a]). \] Thus, the image of \( G_K \) in \( \operatorname{Aut}(\phi[a])\cong \mathrm{GL}_r(A/aA) \) is proportionally smaller to the size of \( \operatorname{End}_K(\phi) \) (larger the endomorphism ring, smaller the image of \( G_K \) will be).

Now suppose \( \phi \) and \( \psi \) have rank 2. The \( j \)-invariant of \( \phi \) is \[ j(\phi):=g_1^{q+1}/g_2. \] It is not hard to check that \( \phi \) and \( \psi \) are isomorphic over \( \overline{K} \) if and only if \( j(\phi)=j(\psi) \).

For a Drinfeld module \( \phi \) of rank \( \geq 3 \) there is a finite collection of \( j \)-invariants, which are rational functions in the coefficients of \( \phi \) and which distinguish the isomorphism class of \( \phi \) over \( \overline{K} \). These were constructed by Potemine [e53]. These \( j \)-invariants are not algebraically independent, which is reflected in the fact that the moduli space of Drinfeld modules of rank \( r\geq 3 \) is not isomorphic to the affine space \( \mathbb{A}^{r-1} \).

A \( \Gamma(\mathfrak{n}) \)-structure on a Drinfeld module \( \phi \) of rank

\( r \) over \( K \), if \( \operatorname{char}_A(K)\nmid \mathfrak{n} \), is an isomorphism of \( A \)-modules

\[

\iota\colon (A/\mathfrak{n})^r \longrightarrow \phi[\mathfrak{n}](K),

\]

where \( \phi[\mathfrak{n}](K) \) is the set of \( K \)-rational \( \mathfrak{n} \)-torsion points of \( \phi \).

A \( \Gamma_1(\mathfrak{n}) \)-structure is an injective homomorphism

\( A/\mathfrak{n} \to \phi[\mathfrak{n}](K) \), and a \( \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n}) \)-structure is a morphism \( \phi\to \psi \) over \( K \) whose kernel is isomorphic to \( A/\mathfrak{n} \).

The notion of Drinfeld module and level structures can be extended

to an arbitrary \( A \)-scheme \( S \) (instead of \( S=\operatorname{Spec}(K) \)): a Drinfeld module over \( S \) is a homomorphism

\( \phi\colon A\to \operatorname{End}(\mathcal{L}) \) from \( A \) to the ring of

\( S \)-endomorphisms of the group scheme underlying a line bundle \( \mathcal{L} \) on \( S \)

satisfying certain conditions, and \( \Gamma(\mathfrak{n}) \)-structure is a homomorphism of \( A \)-modules \( \iota: (A/\mathfrak{n})^r \longrightarrow \phi[\mathfrak{n}](S) \), which

induces an equality of Cartier divisors \( \phi[\mathfrak{n}](S) = \sum_{\alpha\in

(A/\mathfrak{n})^r} \iota(\alpha) \).

There results a moduli functor

\( \mathcal{M}^r(\mathfrak{n}) \) from the category of \( A \)-schemes to the category of sets which to an \( A \)-scheme \( S \) associates the

set \( \mathcal{M}^r(\mathfrak{n})(S) \) of isomorphism classes of Drinfeld modules over \( S \) of rank

\( r \) equipped with a \( \Gamma(\mathfrak{n}) \)-structure.

Under the assumption that \( \mathfrak{n} \) is divisible by at least two primes, Drinfeld proved in

[e10]

that \( \mathcal{M}^r(\mathfrak{n}) \)

is representable by an affine flat \( A \)-scheme \( M^r(\mathfrak{n}) \) of dimension \( r-1 \)

whose fibers over \( \operatorname{Spec}(A) \) are smooth

away from \( \mathfrak{n} \). Taking the quotients of \( M^r(\mathfrak{n}) \) by finite groups one constructs (coarse) moduli schemes \( Y^r_1(\mathfrak{n}) \) and \( Y^r_0(\mathfrak{n}) \)

classifying Drinfeld modules with level \( \Gamma_1(\mathfrak{n}) \) and \( \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n}) \)-structures. One of the connected

components of \( M^r(\mathfrak{n})(\mathbb{C}_\infty) \) is \( Y^r(\mathfrak{n})(\mathbb{C}_\infty) \), constructed earlier as a quotient of \( \Omega^r \)

by the group \( \Gamma(\mathfrak{n}) \) (and similarly, the \( \mathbb{C}_\infty \)-valued points on \( Y^r_1(\mathfrak{n}) \) and \( Y^r_0(\mathfrak{n}) \)

are in bijection with the quotients of \( \Omega^r \) under the action of

\( \Gamma_1(\mathfrak{n}) \) and \( \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n}) \), respectively).

Assume \( r=2 \). Let \( Y_0(\mathfrak{n}):= Y_0^2(\mathfrak{n}) \) and denote by \( X_0(\mathfrak{n}) \) the unique projective smooth geometrically connected curve containing \( Y_0(\mathfrak{n}) \) as an affine subvariety. The set of points \( X_0(\mathfrak{n})-Y_0(\mathfrak{n}) \) are the cusps of \( X_0(\mathfrak{n}) \).

4. Modular forms over \( \mathbb{F}_q(T) \)

4.1. Drinfeld modular forms

- \( f(\gamma \boldsymbol{z}) =(\det \gamma)^{-m} j(\gamma, \boldsymbol{z})^k f(\boldsymbol{z}) \) for all \( \gamma\in \Gamma \), and

- \( f(\boldsymbol{z}) \) is holomorphic at the cusps of \( \Gamma \).

Denote the space of such functions by \( M^r_{k, m}(\Gamma) \). (It is shown in [e116] that \( M^r_{k, m}(\Gamma) \) is finite dimensional over \( \mathbb{C}_\infty \).)

Condition (ii) is technically complicated to explain when \( r\geq 3 \), so we will

explain it only for \( r=2 \), and refer to

[e116]

for \( r\geq 2 \). Because

\( \Gamma \) is a congruence group, it contains the subgroup \( U_b=\left(\begin{smallmatrix} 1 & bA \\ 0 & 1\end{smallmatrix}\right) \) for

some nonzero \( b\in A \). Condition (i) implies that \( f(z+b)=f(z) \), which itself implies that \( f(z) \) can be expanded as

\[

f(z)=\sum_{n\in \mathbb{Z}} a_n (1/e_{bA}(z))^n, \qquad a_n\in \mathbb{C}_\infty,

\]

assuming \( \Im(z):= \inf_{\alpha\in F_\infty}\lvert z-\alpha \rvert\gg 0 \) (for simplicity, we will omit this condition in what follows). We say that \( f(z) \) is holomorphic at the cusp \( [\infty] \) if in the above expansion \( a_n=0 \) for all \( n < 0 \) (this vanishing of coefficients with negative indices does not depend on the choice of \( b \)).

Next, for \( g\in \mathrm{GL}_2(A) \), put \( f|_g (z) = (\det g)^m j(g,z)^{-k}f(g z) \). This

\( f|_g \) satisfies (i) for any \( \gamma \in g^{-1}\Gamma g \), which is again a

congruence group. Condition (ii) means that \( f|_g \) is holomorphic at \( [\infty] \)

for all \( g\in \mathrm{GL}_2(A) \).

(Note that \( f|_g=f \) for \( g\in \Gamma \), so for this last condition to hold it

suffices that \( f|_g \) is holomorphic at \( [\infty] \) for left coset representatives

of \( \Gamma \) in \( \mathrm{GL}_2(A) \).)

The Eisenstein series \( E_{q^n-1}(\boldsymbol{z}):= E_{q^n-1}(\Lambda_{\boldsymbol{z}}) \) defined in (3.1) and the coefficients \( e_{n}(\boldsymbol{z}):= e_{n}(\Lambda_{\boldsymbol{z}}) \) defined in (3.2) are Drinfeld modular forms of weight \( q^n-1 \). It can be shown that the \( \mathbb{C}_\infty \)-algebra of all Drinfeld modular forms of type 0 is a polynomial ring: \begin{align*} \smash[b]{\bigoplus_{k\geq 1} M^r_{k, 0}}(\mathrm{GL}_r(A)) &= \mathbb{C}_\infty[g_1, \dots, g_r] \\ & = \mathbb{C}_\infty[e_1, \dots, e_r]\\ & = \mathbb{C}_\infty[E_{q-1}, E_{q^2-1}, \dots, E_{q^r-1}]. \end{align*}

Now we specialize to \( r=2 \) and \( \Gamma=\Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n}) \). To simplify the notation, we will omit the superscript \( r \), so for example \( \Omega:=\Omega^2 \) and \( M_{k,m}(\mathfrak{n}) := M^2_{k,m}(\Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})) \). Since \( \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n}) \) contains the group of scalar matrices \( \left(\begin{smallmatrix} \alpha & 0 \\ 0 & \alpha\end{smallmatrix}\right) \), \( \alpha\in \mathbb{F}_q^\times \), applying condition (i) to such matrices one concludes that if \( M_{k, m}(\mathfrak{n})\neq 0 \), then \( k\equiv 2m(\operatorname{mod} q-1) \). Hence, if \( q \) is odd and \( M_{k, m}(\mathfrak{n})\neq 0 \), then \( k \) is necessarily even and \( m=k/2 \) or \( m=k/2+(q-1)/2 \) modulo \( q-1 \). Next, a simple calculation shows that the differential \( \mathrm{d} z \) on \( \Omega \) satisfies \[ \mathrm{d}(\gamma z) = \frac{\det(\gamma)}{(cz+d)^2}\,\mathrm{d} z \quad \text{for all }\gamma\in \mathrm{GL}_2(F_\infty). \] Hence, if \( f(z)\in M_{2k, k}(\mathfrak{n}) \), then \( f(z)(\mathrm{d} z)^k \) can be identified with a \( k \)-fold differential form on the Drinfeld modular curve \( X_0(\mathfrak{n}) \).

Since \( \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n}) \) contains the subgroup \( U_1 \), the expansion of a Drinfeld modular form \( f \) at \( [\infty] \) is \( f(z)=\sum_{n\geq 0} a_n (1/e_A(z))^n \). Instead we will now use the parameter \[ t(z) = \frac{1}{\pi_C e_A(z)} = \frac{1}{e_C(\pi_C z)} = \frac{1}{\pi_C} \sum_{a\in A} \frac{1}{z+a}, \] which plays the role of the classical parameter \( q = e^{2i\pi z} \) (this renormalization is chosen so that the expansions of the modular forms \( \pi_C^{1-q} g_1 \) and \( \pi_{C}^{1-q^2} g_2 \) at \( [\infty] \) have coefficients in \( A \)). Then we have \( f = \sum_{n\geq 0} a^{\prime}_n t^n \) with \( a^{\prime}_n \in \mathbb{C}_\infty \). Since \( t(\alpha z)=\alpha^{-1}t(z) \) for any \( \alpha \in \mathbb{F}_q^\times \), the coefficients \( a^{\prime}_n \) are zero unless \( n\equiv m (\operatorname{mod}q-1) \) so the expansion of \( f \) is of the form \[ f = \sum_{i\geq 0} b_i t^{m+i(q-1)}. \] A Drinfeld modular form is said to be cuspidal (resp. doubly cuspidal) at the cusp \( [\infty] \) if \( a^{\prime}_0=0 \) (resp. \( a^{\prime}_0 = 0 \) and \( a^{\prime}_1=0 \)). If for all \( g\in \mathrm{GL}_2(A) \), \( f|_g \) is cuspidal (resp. doubly cuspidal) at \( [\infty] \), we say that the Drinfeld modular form \( f \) is cuspidal (resp. doubly cuspidal). Let \( M_{k,m}^0(\mathfrak{n}) \) (resp. \( M_{k,m}^{0,0}(\mathfrak{n}) \)) denote the subspaces of such functions. Since \( \mathrm{d} e_A(z) / \mathrm{d} z=1 \), we have \( \mathrm{d} t = -\pi_C t^2 \mathrm{d} z \) so doubly cuspidal Drinfeld modular forms play a role similar to classical cusp forms. Namely the map \( f(z) \mapsto f(z) \mathrm{d} z \) is an isomorphism between \( M_{2,1}^{0,0}(\mathfrak{n}) \) and the space of holomorphic differential forms on the curve \( X_0(\mathfrak{n}) \). In particular the dimension of \( M_{2,1}^{0,0}(\mathfrak{n}) \) is equal to the genus of \( X_0(\mathfrak{n}) \).

Hecke operators on Drinfeld modular forms can be defined as double coset operators for \( \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n}) \). Let \( \mathfrak{m} \lhd A \) be a nonzero ideal of \( A \). For the double coset \( \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n}) \setminus (\Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n}) \left(\begin{smallmatrix}\mathfrak{m}&0\\0&1\end{smallmatrix}\right) \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})) \), a set of representatives is \begin{equation}\label{eq-Sm} S_{\mathfrak{m}}=\bigl\{ \left(\begin{smallmatrix} a & b \\ 0 & d \end{smallmatrix}\right) \in M_2(A) : a,d \text{ monic}, (ad) = \mathfrak{m}, (a)+\mathfrak{n} = A, \deg b < \deg d\bigr\}.\tag{4.2} \end{equation} For \( f \in M_{k,m}(\mathfrak{n}) \), we define \( f|T_\mathfrak{m} = \sum_{g\in S_{\mathfrak{m}}} f|_g \). In more concrete terms \[ f|T_{\mathfrak{m}}\, (z) = \frac{1}{\mathfrak{m}^{k-m}} \sum_{\left(\begin{smallmatrix}a&b\\0&d\end{smallmatrix}\right) \in S_\mathfrak{m}} f\left( \frac{az+b}{d} \right). \] The \( \mathfrak{m} \)-th Hecke operator \( T_\mathfrak{m} \) is a \( \mathbb{C}_\infty \)-linear transformation of the space \( M_{k,m}(\mathfrak{n}) \). It stabilizes the cuspidal and doubly-cuspidal subspaces. The Hecke operators \( (T_\mathfrak{m})_{\mathfrak{m}\lhd A} \) generate a commutative \( \mathbb{C}_\infty \)-subalgebra of \( M_{k,m}(\mathfrak{n}) \), called the Hecke algebra for \( M_{k,m}(\mathfrak{n}) \). On Drinfeld modular forms, Hecke operators are completely multiplicative, i.e., for all \( \mathfrak{m},\mathfrak{m}^{\prime} \lhd A \), we have \( T_\mathfrak{m} T_{\mathfrak{m}^{\prime}} = T_{\mathfrak{m} \mathfrak{m}^{\prime}}=T_{\mathfrak{m}^{\prime}} T_\mathfrak{m} \). This property distinguishes them from Hecke operators on classical modular forms, where they are only multiplicative.

Another important difference is that, the characteristic being positive, the space \( M_{k,m}^{0,0}(\mathfrak{n}) \) has no inner product. Hence there is no guarantee that \( T_\mathfrak{m} \) is diagonalizable. Goss was the first to point out this problem [e16]. Since then, examples of nondiagonalizable Hecke operators have been obtained in special cases (see [e70] for the subgroups \( \Gamma_1(T) \) and \( \Gamma(T) \)) but in general, the question is still wide open. In particular we know no natural bases of Drinfeld modular forms which are simultaneously eigenforms for the Hecke operators.

4.2. Harmonic cochains

Harmonic cochains on simplicial complexes naturally arise in the study of combinatorial laplacians; see [e8]. A variant of harmonic \( i \)-cochains on \( \mathscr{B}^r \) was defined by de Shalit [e54]: these are functions on pointed \( i \)-simplices of \( \mathscr{B}^r \), \( 1\leq i\leq r-1 \), satisfying certain conditions (in [e54] the building \( \mathscr{B}^r \) is defined over an arbitrary local field). The significance of the group \( \operatorname{Har}^i(\mathscr{B}^r, \mathbb{Q}_\ell) \) of \( \mathbb{Q}_\ell \)-valued harmonic \( i \)-cochains is that it is isomorphic to the \( \ell \)-adic cohomology group \( H^i_{\mathrm{et}}(\Omega^r, \mathbb{Q}_\ell) \) of \( \Omega^r \); see [e32], [e54]. Also, \( \operatorname{Har}^i(\mathscr{B}^r, \mathbb{Q}_\ell) \) can be interpreted as a space of automorphic forms on the adele group \( \mathrm{GL}_r(\mathbb{A}_F) \) with special restriction at \( \infty \); see [e68] (one transforms functions on \( \mathrm{GL}_r(\mathbb{A}_F) \) to functions on \( \mathrm{GL}_r(F_\infty) \) using the strong approximation theorem and uses the bijections between the sets of simplices of \( \mathscr{B}^r \) and cosets in \( \operatorname{PGL}_r(F_\infty) \) mentioned earlier).

The most relevant for our purposes are the harmonic 1-cochains, which for \( r=2 \) were already defined by van der Put in [e21].

- \( f(e)+f(\overline{e})=0\quad\text{ for all }\,e\in \mathrm{Ed}(\mathscr{B}^2). \)

- \( \sum_{\substack{e\in \mathrm{Ed}(\mathscr{B}^2)\\o(e)=v}}f(e)=0\quad\text{ for all }\,v\in \mathrm{Ver}(\mathscr{B}^2). \)

Here, \( o(e) \) is the origin of \( e \) and \( \bar{e} \) is the edge \( e \) with opposite orientation.

When \( r\geq 3 \), two of the conditions that define harmonic 1-cochains are similar to (1) and (2), with (2) refined by the “types” of edges, where \( \mathrm{type}([L_0], [L_1])=\dim_{\mathbb{F}_q}L_0/L_1 \). But there are two additional conditions. One of these conditions says that the sum of values of \( f \) over the edges of a closed path in \( \mathscr{B}^r \) is 0, and the other that the values of \( f \) are uniquely determined by its values on edges of type 1. We denote the space of \( R \)-valued harmonic 1-cochains by \( \operatorname{Har}^1(\mathscr{B}^r, R) \).

From another perspective, \( \mathscr{B}^r \) is a combinatorial “skeleton” of \( \Omega^r \). In fact, there is an admissible covering of \( \Omega^r \) through affinoid subspaces and a \( \mathrm{GL}_r(F_\infty) \)-equivariant map \( \Omega^r\to \mathscr{B}^r \) that sends affinoids to simplices; see [e10]. The following important result relates the group of holomorphic invertible functions \( \mathcal{O}(\Omega^r)^\times \) on \( \Omega^r \) to \( \mathbb{Z} \)-valued harmonic 1-cochains on \( \mathscr{B}^r \): \begin{equation}\label{eqGvdP} 0 \longrightarrow \mathbb{C}_\infty^\times \longrightarrow \mathcal{O}(\Omega^r)^\times \xrightarrow{\mathrm{dlog}} \mathrm{Har}^1(\mathscr{B}^r, \mathbb{Z})\longrightarrow 0, \tag{4.3} \end{equation} where \( \mathrm{dlog} \) is some sort of a logarithmic derivative. The existence of \eqref{eqGvdP} was proved by van der Put for \( r=2 \) and extended to arbitrary \( r\geq 2 \) by Gekeler [e99].

From now on, the discussion will focus mostly on harmonic 1-cochains on the

Bruhat–Tits tree \( \mathscr{B}^2 \). To simplify the notation, we denote \( \mathscr{T}=\mathscr{B}^2 \). The

group \( \mathrm{GL}_2(F_\infty) \) acts on \( \mathscr{T} \) from the left. Let

\[

\mathcal{H}(\mathfrak{n}, R):= \operatorname{Har}^1(\mathscr{T}, R)^{\Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})}

\]

be the submodule of \( R \)-valued harmonic 1-cochains such that \( f(\gamma

e)=f(e) \) for all \( \gamma\in \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n}) \) and \( e\in \mathrm{Ed}(\mathscr{T}) \).

The module of \( R \)-valued \( \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n}) \)-invariant cuspidal harmonic cochains, denoted \( \mathcal{H}_0(\mathfrak{n}, R) \), is the submodule of \( \mathcal{H}(\mathfrak{n}, R) \) consisting of functions which have compact

support as functions on \( \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})\setminus \mathscr{T} \), i.e., functions which have

value 0 on all but finitely many edges of \( \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})\setminus \mathscr{T} \). We denote by \( \mathcal{H}_{00}(\mathfrak{n}, R) \) the image

of \( \mathcal{H}_0(\mathfrak{n},\mathbb{Z})\otimes_{\mathbb{Z}} R \) in \( \mathcal{H}_0(\mathfrak{n},

R) \). (It is easy to construct examples where the inclusion

\( \mathcal{H}_{00}(\mathfrak{n}, R)\subseteq \mathcal{H}_0(\mathfrak{n}, R) \)

is strict; see

([e85],

Section 1.1).)

It is known that the quotient

graph \( \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})\setminus \mathscr{T} \) is the edge disjoint union

\[

\Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})\setminus \mathscr{T} = (\Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})\setminus \mathscr{T})^0\cup \bigcup_{s\in \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})\setminus \mathbb{P}^1(F)} h_s

\]

of a finite graph \( (\Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})\setminus \mathscr{T})^0 \) with a finite number of half-lines

\( h_s \), called cusps. The cusps are in bijection with the orbits of the

natural (left) action of \( \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n}) \) on \( \mathbb{P}^1(F) \).

It is clear that \( f\in \mathcal{H}(\mathfrak{n}, R) \) is cuspidal if and only if it eventually vanishes on each \( h_s \).

One can show that \( \mathcal{H}_0(\mathfrak{n}, \mathbb{Z}) \) and \( \mathcal{H}(\mathfrak{n}, \mathbb{Z}) \) are finitely generated free

\( \mathbb{Z} \)-modules of rank \( g(\mathfrak{n}) \) and \( g(\mathfrak{n})+c(\mathfrak{n})-1 \), respectively, where \( g(\mathfrak{n}) \)

is the genus of the curve \( X_0(\mathfrak{n}) \) and \( c(\mathfrak{n}) \) is the number of its cusps.

Harmonic 1-cochains invariant under congruence groups have Fourier expansions. This theory for \( r=2 \) was first developed by Weil in adelic language, and recast into more explicit formulas by Gekeler [e43] and Pál [e66]. The theory was extended to arbitrary \( r\geq 2 \) in [e112]. We briefly discuss the \( r=2 \) case.

The edges of \( \mathscr{T} \) are in bijection with \( \mathrm{GL}_2(F_\infty)/F_\infty^\times \mathcal{I}_\infty \), where \( \mathcal{I}_\infty \) is the Iwahori group: \[ \mathcal{I}_\infty:=\left\{\begin{pmatrix} a & b\\ c & d\end{pmatrix}\in \mathrm{GL}_2(\mathcal{O}_\infty)\ \bigg|\ c\in \pi_\infty\mathcal{O}_\infty\right\}. \] Let \[ \mathrm{Ed}(\mathscr{T})^+:=\left\{\begin{pmatrix} \pi_\infty^k & u \\ 0 & 1\end{pmatrix}\ \bigg|\ \begin{matrix} k\in \mathbb{Z}\\ u\in F_\infty,\ u\mod{\pi_\infty^k\mathcal{O}_\infty}\end{matrix}\right\}. \] It is not hard to show that \[ \mathrm{Ed}(\mathscr{T})=\mathrm{Ed}(\mathscr{T})^+\sqcup \mathrm{Ed}(\mathscr{T})^+ \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1\\ \pi_\infty & 0\end{pmatrix}. \]

Assume that \( R \) is a ring such that \( p\in R^\times \) and \( R \) contains the \( p \)-th roots of unity. A function \( f\in \mathcal{H}(\mathfrak{n}, R) \) has a Fourier expansion \[ f \left(\begin{pmatrix} \pi_\infty^k & u \\ 0 &1\end{pmatrix}\right) = f^0(\pi_\infty^k)+ \sum_{0\leq j\leq k-2} q^{-k+2+j}\sum_{\substack{\mathfrak{m}\in A\text{, monic}\\ \deg(\mathfrak{m})=j}}f^\ast(\mathfrak{m})\, \nu(\mathfrak{m} u), \] where \( \nu(x):=-1 \) if \( x \) has a term of order \( \pi_\infty \) in its \( \pi_\infty \)-expansion; \( \nu(x):=q-1 \) otherwise. Here the Fourier coefficients \( f^0(\pi_\infty^k) \) and \( f^\ast(\mathfrak{m}) \) are certain finite sums of values of \( f \) twisted by a character \( \chi\colon F_\infty\to \mathbb{C}^\times \) taking values in the \( p \)-th roots of unity. Moreover, the constant Fourier coefficient \( f^0(\pi_\infty^k) \) is equal to 0 for cuspidal harmonic cochains.

Following Weil, one can attach a Dirichlet \( L \)-series to a cuspidal harmonic cochain \( f \in \mathcal{H}_0(\mathfrak{n},\mathbb{C}) \). Put \[ L (f,s) = \sum_{\mathfrak{m}} f^*(\mathfrak{m}) |\mathfrak{m} |^{-s-1}, \] where the sum is over all nonnegative divisors on \( F \). This \( L \)-series is defined for \( s\in\mathbb{C} \), is a polynomial in \( q^{-s} \), and satisfies a functional equation when substituting \( s \mapsto 2-s \).

Fix a nonzero ideal \( \mathfrak{n}\lhd A \). Given a nonzero ideal \( \mathfrak{m}\lhd A \), define an \( R \)-linear transformation of the space of \( R \)-valued functions on \( \mathrm{Ed}(\mathscr{T}) \) by \begin{equation}\label{eqDefTm} f|T_\mathfrak{m}:=\sum_{g\in S_{\mathfrak{m}}} f|_g, \tag{4.4} \end{equation} where the set \( S_{\mathfrak{m}} \) has been defined in \eqref{eq-Sm}. This transformation is the Hecke operator \( T_\mathfrak{m} \). Following a common convention, for a prime divisor \( \mathfrak{p} \) of \( \mathfrak{n} \) one sometimes writes \( U_\mathfrak{p} \) instead of \( T_\mathfrak{p} \).

The group-theoretic proofs of the properties of Hecke operators acting on classical modular forms also work in this setting. In particular, the Hecke operators preserve \( \mathcal{H}_0(\mathfrak{n}, R) \), and satisfy the recursive formulas \begin{align*} T_{\mathfrak{m}\mathfrak{m}^{\prime}}&= T_\mathfrak{m} T_{\mathfrak{m}^{\prime}}&\quad \text{if}\quad \mathfrak{m}+\mathfrak{m}^{\prime}=A,\\ T_{\mathfrak{p}^i} &= T_{\mathfrak{p}^{i-1}}T_\mathfrak{p}-|\mathfrak{p}|T_{\mathfrak{p}^{i-2}}\quad \text{if}\quad \mathfrak{p}\nmid \mathfrak{n}, \\ T_{\mathfrak{p}^i} &= T_\mathfrak{p}^i\quad \text{if}\quad \mathfrak{p}| \mathfrak{n}. \end{align*} Let \( \mathbb{T}(\mathfrak{n}) \) be the commutative \( \mathbb{Z} \)-subalgebra of \( \operatorname{End}_\mathbb{Z}(\mathcal{H}_0(\mathfrak{n}, \mathbb{Z})) \) generated by all Hecke operators.

An explicit formula can be given for the action of \( T_\mathfrak{m} \) on the Fourier expansion of \( f\in \mathcal{H}_0(\mathfrak{n}, R) \). This formula implies that \begin{equation}\label{eqfTm} (f|T_\mathfrak{m})^\ast(1)=|\mathfrak{m}|f^\ast(\mathfrak{m}). \tag{4.5} \end{equation} Thus, the pairing \begin{equation}\label{eqPairing} \begin{array}{ccc} \mathbb{T}(\mathfrak{n})\times \mathcal{H}_0(\mathfrak{n}, \mathbb{Z}) & \longrightarrow & \mathbb{Z} \\ ( T, f) & \longmapsto & (f|T_\mathfrak{m})^\ast(1) \end{array}\tag{4.6} \end{equation} is nondegenerate and becomes perfect after tensoring with \( \mathbb{Z}[p^{-1}] \).

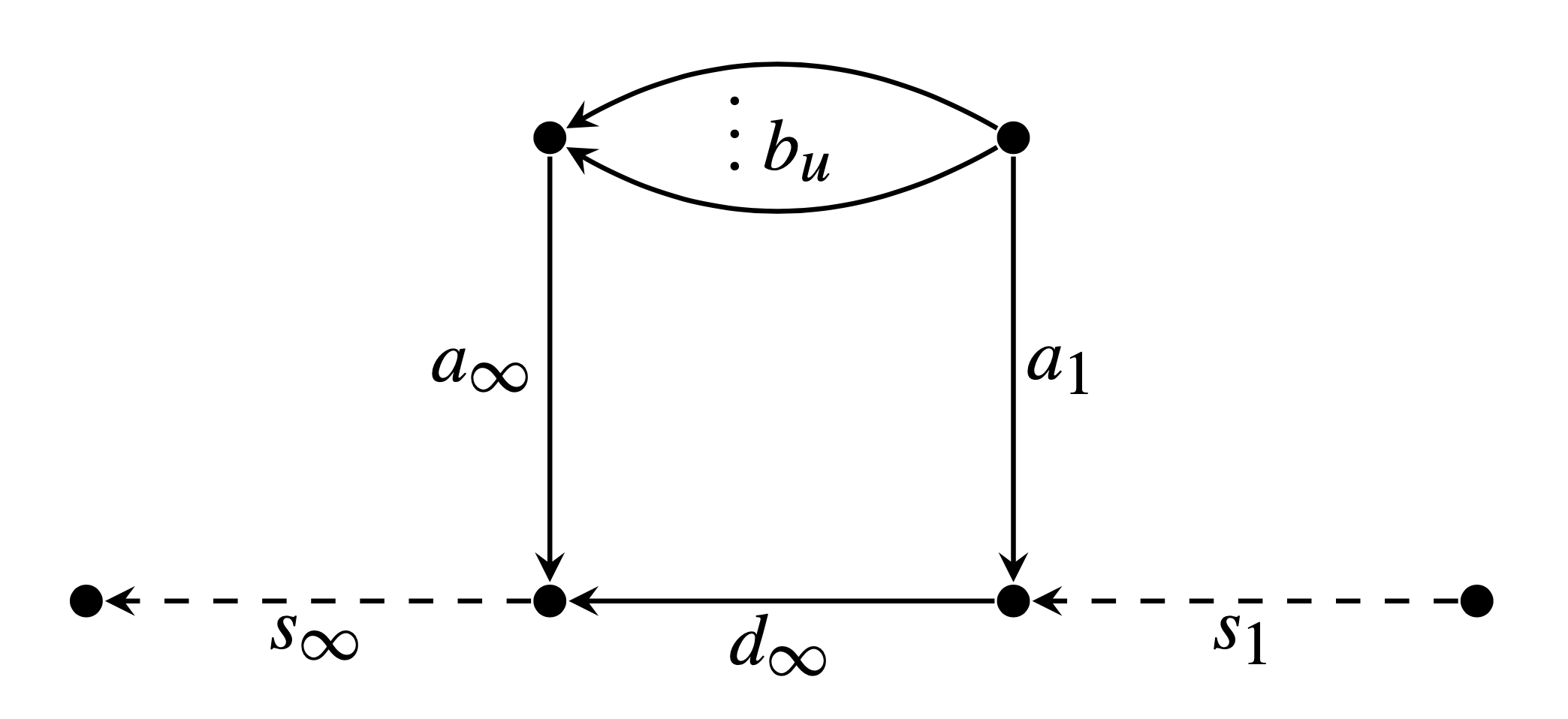

Let \( \mathfrak{p}\lhd A \) be a prime of degree 3. In this case, the quotient graph \( \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{p})\setminus \mathscr{T} \) looks like the graph in Figure 1; see ([e87], Section 4.1).

The matrix representatives of the edges are the following.

- The dashed edges \[ s_\infty=\begin{pmatrix} \pi_\infty & 0 \\0&1\end{pmatrix}, \quad s_1=\begin{pmatrix} \pi_\infty^3 & 0 \\0&1\end{pmatrix} \] indicate that they are the first edges on a half-line corresponding to the cusps \( [\infty] \) and \( [0] \), respectively;

- \[ a_\infty=\begin{pmatrix} \pi_\infty^2 & \pi_\infty \\0&1\end{pmatrix}, \quad a_1=\begin{pmatrix} \pi_\infty^3 & \pi_\infty^2 \\0&1\end{pmatrix}, \quad d_\infty=\begin{pmatrix} \pi_\infty^2 & 0 \\0&1\end{pmatrix}; \]

- There are \( q \) edges \[ b_u = \begin{pmatrix} \pi_\infty^3 & \pi_\infty + u \pi_\infty^2 \\0&1\end{pmatrix}, \quad u \in \mathbb{F}_q. \]

Let \( E:= \mathrm{dlog}(\Delta/\Delta_{\mathfrak{p}})\in \mathcal{H}(\mathfrak{p}, \mathbb{Z}) \), where \( \Delta = \Delta_2 \) and \( \Delta_{\mathfrak{p}}(z) :=\Delta(\mathfrak{p} z) \). One can compute the values of \( E \) on the edges of \( \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{p})\setminus \mathscr{T} \) using ([e49], Corollary 2.9) and ([e114], Lemma 2.4):

- \( E(s_\infty) = E(s_1) = (q^2+q+1)(q-1)^2 \).

- \( E(a_\infty) = E(\overline{a_1}) = q(q-1)^2 \) and \( E(d_\infty) = (2q+1)(q-1)^2 \).

- \( E(b_u) = (q-1)^2 \) for \( u\in \mathbb{F}_q \).

By ([e49], Corollary 2.11) and ([e115], Lemma 4.4), we have \[ E|U_{\mathfrak{p}}=E \quad \text{and}\quad E|T_\mathfrak{q} = (|\mathfrak{q}|+1)E\quad \text{for all prime }\, \mathfrak{q}\neq \mathfrak{p}. \] By using this and applying ([e49], (2.5) and Corollary 2.8) and [e115], Lemma 3.6), one can compute the Fourier coefficients of \( E \):

- \( E^0(\pi_\infty^k) = q^{1-k} (q^2+q+1)(q-1)^2 \).

- \( E^\ast(1) = q^{-1}(q+1)(q-1)^2 \).

- \( E^\ast(\mathfrak{m}) = \frac{(q+1)(q-1)^2}{q\, |\mathfrak{m}|} \, \prod_{i=1}^s \frac{|\mathfrak{q}_i|^{k_i+1}-1}{|\mathfrak{q}_i|-1}\, \) for \( \,\mathfrak{m} = \mathfrak{p}^k \, \prod_{i=1}^s {\mathfrak{q}_i}^{k_i}\lhd A \).

Note that, similar to the appearance of the divisor function in the Fourier expansions of classical Eisenstein series ([e67], p. 100), the factor \( (\lvert\mathfrak{q}\rvert^{k+1}-1)/(\lvert\mathfrak{q}\rvert-1)=\lvert\mathfrak{q}\rvert^k+\cdots+\lvert\mathfrak{q}\rvert+1 \) in the expression for \( E^\ast(\mathfrak{m}) \) is a version of the divisor function for \( \mathfrak{q}^{k+1} \). We also point out that the term \( (q^2+q+1) \) in \( E^0(\pi_\infty^k) \) is the order of the cuspidal divisor group of \( X_0(\mathfrak{p}) \), and this type of relation is important in the proofs in Section 6.

The analogue of the Petersson inner product in this setting is the pairing on \( \mathcal{H}_0(\mathfrak{n}, \mathbb{C}) \) defined by \[ (f, g) =\sum_{e\in \mathrm{Ed}(\Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})\setminus \mathscr{T})} f(e)\overline{g(e)} \mu(e)^{-1}, \] where \( \mu(e)=\frac{q-1}{2}\# \operatorname{Stab}_{\Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})}(\tilde{e}) \) and \( \tilde{e} \) is a preimage of \( e \) in \( \mathscr{T} \). (A Haar measure on \( \mathrm{GL}_2(F_\infty) \) induces a push-forward measure on \( \mathrm{Ed}(\Gamma_0(\mathfrak{n})\setminus \mathscr{T}) \), which, up to a scalar multiple, is equal to \( \mu(e) \).) The Hecke operators \( T_\mathfrak{m} \), \( (\mathfrak{n}, \mathfrak{m})=1 \), are self-adjoint with respect to this pairing. Hence, the usual conclusions about Hecke operators being diagonalizable and their eigenvalues being real are also valid in this setting.

The Hecke operators may also be defined using correspondences on \( X_0(\mathfrak{n}) \). Recall the moduli interpretation of \( Y_0(\mathfrak{n}) \): it is the generic fiber of the coarse moduli scheme for pairs \( (\phi,G_\mathfrak{n}) \) consisting of a Drinfeld \( A \)-module \( \phi \) of rank 2 over \( F \) with an \( F \)-rational \( A \)-submodule \( G_\mathfrak{n} \) of \( \phi[\mathfrak{n}] \) isomorphic to \( A/\mathfrak{n} \) (\( F \)-rational means that \( \sigma(G_\mathfrak{n})=G_\mathfrak{n} \) for all \( \sigma\in \operatorname{Gal}(F^{\mathrm{alg}}/F) \)). For \( \mathfrak{m} \lhd A \), the Hecke operator \( T_\mathfrak{m} \) is defined as the correspondence on \( Y_0(\mathfrak{n}) \) given by \[ T_\mathfrak{m} : (\phi,G_\mathfrak{n}) \mapsto \sum_{G_\mathfrak{m} \cap G_\mathfrak{n} = \{ 0 \} } (\phi/G_\mathfrak{m} , (G_\mathfrak{n} + G_\mathfrak{m})/G_\mathfrak{m}). \] It uniquely extends to \( X_0(\mathfrak{n}) \). The resulting correspondence induces an endomorphism of the Jacobian variety \( J_0(\mathfrak{n}) \) of \( X_0(\mathfrak{n}) \), also denoted \( T_\mathfrak{m} \). The \( \mathbb{Z} \)-subalgebra of \( \operatorname{End}(J_0(\mathfrak{n})) \) generated by \( (T_{\mathfrak{m}})_{\mathfrak{m} \lhd A} \) is canonically isomorphic to \( \mathbb{T}(\mathfrak{n}) \); this is a consequence of Drinfeld’s Reciprocity Law ([e10], Theorem 2). Having this fact, one can use the classical Shimura construction to associate to a \( \mathbb{T}(\mathfrak{n}) \)-eigenform \( f\in \mathcal{H}_0(\mathfrak{n}, \mathbb{C}) \) an abelian variety \( B_f \) whose number of points over \( \mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{p} \), \( \mathfrak{p}\nmid \mathfrak{n} \), is computed using the eigenvalue of \( T_\mathfrak{p} \) acting on \( f \). In particular, if \( f \) has rational eigenvalues, then \( B_f \) is an elliptic curve over \( F \). Combining this with some deep results of Grothendieck and Deligne, one can deduce the following analogue of the Modularity Theorem (see ([e47], (8.3))).

The quotient \( \mathbb{T}(\mathfrak{n})/\mathfrak{E}(\mathfrak{n}) \) is a finite ring. Indeed, otherwise the perfectness of the pairing \eqref{eqPairing} implies that there is a nonzero \( f\in \mathcal{H}_{0}(\mathfrak{n}, \mathbb{Q}) \) annihilated by \( \mathfrak{E}(\mathfrak{n}) \), which contradicts Weil’s bounds using the Shimura construction mentioned earlier.

(2) Depending on the problem where it is used, the definition of Eisenstein ideal might be modified to include elements of the form \( U_\mathfrak{p}+a \) or \( W_\mathfrak{p}+a \), where \( \mathfrak{p}\mid \mathfrak{n} \), \( a\in \mathbb{Z} \), and \( W_\mathfrak{p} \) is an Atkin–Lehner involution; see [e87], [e90], [e114].

5. Torsion of Drinfeld modules

5.1. Analogue of Ogg’s conjecture

(2) As of 2024, Conjecture TDM remains largely open. On the other hand, under an extra

assumption, it is easy to prove. We say that the Drinfeld

module \( \phi \) defined over \( F \) by

\( \phi_T(x)=Tx+g_1x^q+\cdots+g_r x^{q^r} \) has good

reduction at the prime \( \mathfrak{l}\lhd A \) if

\( \operatorname{ord}_{\mathfrak{l}}(g_i)\geq 0 \) for \( 1\leq

i\leq r \) and \( \operatorname{ord}_{\mathfrak{l}}(g_r)=0 \). If

\( \phi \) has good reduction at \( \mathfrak{l} \), then reducing the

coefficients of \( \phi_T \) modulo \( \mathfrak{l} \), one obtains a

Drinfeld module \( \bar{\phi} \) over \( \mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{l} \) of the same rank.

It is not hard to show that the reduction modulo

\( \mathfrak{l} \)

induces an injection \( ({^\phi}F)_\mathrm{tor}\hookrightarrow

({^{\bar{\phi}}}\mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{l})_\mathrm{tor} \); see

([e109],

Theorem 6.5.10).

Thus, \( \# ({^\phi}F)_\mathrm{tor}\leq

\lvert\mathfrak{l}\rvert \). In particular, if after replacing \( \phi \) by an

isomorphic Drinfeld module it acquires good reduction at a

prime of degree \( \leq 2 \), then Conjecture TDM holds for \( \phi \).

(3) It seems like an interesting and important problem to give an explicit conjectural classification of possible \( F \)-rational torsion submodules of Drinfeld modules of rank 3, possibly using the geometry of Drinfeld modular surfaces as a guide.

Following Ogg’s philosophy on the existence of rational points on modular curves, we may also formulate the following conjecture which is an analogue of TEC\( ^+ \). It is supported by the fact that the curve \( X_0(\mathfrak{p}) \) has nonzero genus if and only if \( \deg \mathfrak{p} \geq 3 \) (and this genus is then at least 2), and by the list of all ideals \( \mathfrak{n} \) of \( A \) with \( \deg \mathfrak{n}\geq 3 \) such that \( Y_0(\mathfrak{n}) \) has a \( F \)-rational CM point; see [e58].

There is also an analogue of Conjecture UBC for Drinfeld modules of arbitrary rank \( r \). If \( r\geq 2 \), it is reminiscent of the uniform boundedness conjecture for the torsion of abelian varieties over a number field.

(2) This conjecture in [e51] is stated for more general rings \( A \), namely those of regular functions on the affine curve obtained by removing a closed point from a nonsingular projective curve over \( \mathbb{F}_q \). This more general conjecture reduces to UBC-DM for \( \mathbb{F}_q[T] \) since any Drinfeld \( A \)-module can be considered as a Drinfeld \( \mathbb{F}_q[T] \)-module of higher rank. An earlier formulation of the conjecture can be found in Problème 3 of [e44].

(3) For rank-1 Drinfeld modules, Poonen [e51] gave several proofs of this conjecture, including an explicit bound on the size of the torsion. (For example, \( \# ({^\phi}F)_\mathrm{tor}\leq q \) if \( \phi \) has rank 1 and \( q\neq 2 \).) See also [e59] and [e58] for other proofs or improvements in this case. A fact essential for the proofs is that any rank-1 Drinfeld module defined over \( L \) becomes isomorphic to the Carlitz module over an extension of \( L \) of degree \( \leq q-1 \).

(4) It is possible to reformulate Conjectures TDM and UBC-DM in an equivalent, elementary form, which makes no reference to Drinfeld modules; see [e52], [e63]. Using terminology from arithmetic dynamics, we say that \( \alpha\in L \) is a preperiodic point for the polynomial \( f(x)\in L[x] \) if the set \[ \{\alpha, f(\alpha), f(f(\alpha)), f(f(f(\alpha))),\dots\} \] is finite. Note that for a Drinfeld module \( \phi \) over \( L \), the set of preperiodic points of \( \phi_T(x) \) is exactly \( ({^\phi}L)_\mathrm{tor} \). Thus, Conjecture TDM can be stated as saying that for any \( f(x)=Tx+gx^q+\Delta x^{q^2}\in F[x] \), with \( \Delta\neq 0 \), the set of preperiodic points in \( F \) has cardinality at most \( q^2 \). Also, Ingram [e76] has proposed a perspective on Conjecture UBC-DM via the adelic filled Julia set attached to the Drinfeld module when viewed as a dynamical system, with applications to certain families of rank-\( r \) Drinfeld modules.

(5) A version of Conjecture UBC for elliptic curves over function fields is relatively easy to prove, and was already done by Levin [e4] in 1968. Similarly, let \( L \) be a field of transcendence degree 1 over \( F^\mathrm{alg} \), and let \( \phi \) be a Drinfeld module of rank 2 over \( L \) such that \( j(\phi)\not\in F^\mathrm{alg} \). Schweizer proved in [e62] that \[ \# ({^\phi}L)_\mathrm{tor}\leq (\gamma^2(q^2+1)(q+1))^{q/(q-1)}, \] where \( \gamma \) is the gonality of \( L \).

In rank 2, Conjecture UBC-DM is currently open in general but progress has been made. Recall that a first and important step for the proof of Conjecture UBC was Manin’s result [e5], namely a uniform bound on the \( p \)-primary torsion of elliptic curves over a number field \( L \), depending on \( p \) and \( L \). Its analogue for Drinfeld \( A \)-modules of rank 2 has been established by Poonen [e51]. The following theorem of Schweizer improves this result by making the constant depend only on the prime of \( A \) and the degree of \( L \) (see also [e84] for a generalization to more general function fields than \( F \)).

As a consequence, Conjecture UBC-DM in the rank-2 case is reduced to the problem of bounding uniformly the number

of primes \( \mathfrak{p} \) in the primary decomposition of the torsion,

which is equivalent to proving that for any \( d\geq 1 \), there exists a constant \( C > 0 \) such that if \( \mathfrak{p} \) is a prime of \( A \) with \( \deg\mathfrak{p} \geq C \) and \( L \) is an extension of \( F \) of degree \( \leq d \), then \( Y_1(\mathfrak{p}) \) has no \( L \)-rational points.

Recently and for arbitrary rank, Ishii proved a version of Manin’s uniformity result on the \( \mathfrak{p} \)-primary torsion for one-dimensional families of Drinfeld modules over a finitely generated extension of \( F \), which is the analogue of a result of Cadoret and Tamagawa [e77] for 1-dimensional families of abelian varieties.

Besides this result, not much is currently known towards

Conjecture UBC-DM in ranks \( r\geq 3 \).

We make a few comments about the analogue of Conjecture SUQ. In a series of papers culminating in [e71], Richard Pink and his collaborators proved the following analogue of Serre’s Open Image Theorem.

The analogue of Conjecture SUQ is the statement that the bound \( N(\phi, L) \) in Theorem 5.5 can be made uniform, i.e., independent of \( \phi \). For \( r=1 \) this not hard to prove, but it remains a major open question for \( r\geq 2 \).

(2) In [e103], extending a construction of Zywina for \( r=2 \), Chen proved that for the rank-\( r \) Drinfeld module over \( F \) defined by \[ \phi_T=Tx+x^{q^{r-1}}+T^{q-1}x^{q^r} \] the representations \( \rho_{\phi, \mathfrak{n}}\colon G_F\to \mathrm{GL}_r(A/\mathfrak{n}) \) are surjective for all \( \mathfrak{n}\neq 0 \), assuming \( r \) is prime, \( q\equiv 1(\operatorname{mod} r) \), and the characteristic of \( F \) is sufficiently large compared to \( r \).

We now turn to known results on Conjectures TDM and TDM\( ^+ \), some of which have consequences for Conjecture UBC-DM. In 2010, Pál made major progress by proving Conjecture TDM\( ^+ \) for the case \( q=2 \), i.e., the field \( F = \mathbb{F}_2(T) \).

The previous theorem implies that Conjecture TDM and Conjecture UBC-DM hold for \( q = 2 \) and \( L = F = \mathbb{F}_2(T) \); see Theorems 1.4 and 1.6 in [e72]. In a different direction and more recently, Ishii made more progress towards Conjecture TDM\( ^+ \) for arbitrary \( q \) and levels of small degree.

For Conjecture TDM, Schweizer proved that we always have \( \deg \mathfrak{m} \leq 1 \) in \( (^\phi F)_\mathrm{tor}\cong A/\mathfrak{m}\oplus A/\mathfrak{n} \); see Proposition 4.4 in [e58]. Moreover since any \( F \)-rational point on \( Y_1(\mathfrak{p}) \) naturally provides an \( F \)-rational point on \( Y_0(\mathfrak{p}) \), Theorems 5.7 and 5.8 remain valid for the curve \( Y_1(\mathfrak{p}) \).

For finite extensions of \( F \), Armana has obtained partial or conditional results towards Conjectures TDM and UBC-DM. The first one focuses on levels of small degree.

- If \( \mathfrak{p} \) is of degree 3, the curve \( Y_1(\mathfrak{p}) \) has no \( L \)-rational points for any extension \( L/F \) of degree \( \leq 2 \).

- Suppose \( \mathfrak{p} \) is of degree 4. Let \( d = 1 \) if \( q < 5 \), \( d = 2 \) if \( q = 5 \), and \( d = 3 \) if \( q \geq 7 \). Then the curve \( Y_1(\mathfrak{p}) \) has no \( L \)-rational points for any extension \( L/F \) of degree \( \leq d \).

- Let \( \mathfrak{p} \) be a prime of \( A \) such that for any normalized Hecke eigenform \( f \in \mathcal{H}_{0}(\mathfrak{p},\mathbb{C}) \), we have \( \operatorname{ord}_{s=1}L(f,s) \leq 1 \). Then the curve \( Y_1(\mathfrak{p}) \) has no \( L \)-rational points for any extension \( L/F \) of degree \( < \min (\deg \mathfrak{p}, |\mathfrak{p}|/(2(q^2+1)(q+1))) \).

Given a prime \( \mathfrak{p} \), the assumption in (iii) on the vanishing order of \( L \)-series at the central value is not always satisfied. However, if one believes in the philosophy that elliptic curves over \( \mathbb{Q} \) with rank greater than 1 are expected to be rare and in its counterpart for elliptic curves over \( F \), we should get many examples of pairs \( (q,\mathfrak{p} \)) to which statement (iii) applies. For instance it applies to curves \( Y_1(\mathfrak{p}) \) for all prime levels \( \mathfrak{p} \) of degree 5 in \( \mathbb{F}_2[T] \) with \( L=F \), and for \( \mathfrak{p}=T^5-T^4-T^2-1 \in \mathbb{F}_3[T] \) with \( [L:F]\leq 3 \). There is also a similar result for \( F \)-rational points on \( Y_0(\mathfrak{p}) \) when \( q\geq 5 \), under the same hypothesis as in (iii); see ([e78], Theorem 7.8).

The second result is conditional but with a more general conclusion towards Conjecture TDM. To state it we need some notation. Similarly to classical modular forms, it is possible to develop a theory of algebraic Drinfeld modular forms of weight 2 using sections of the sheaf of relative differentials on \( X_0(\mathfrak{p}) \). Let \( \mathcal{M}_{\mathfrak{p}} \) be the \( A[1/\mathfrak{p}] \)-module of doubly cuspidal algebraic Drinfeld modular forms of weight 2 and type 1 for \( \Gamma_0(\mathfrak{p}) \) and let \( \mathbb{T}_{\mathfrak{p}} \) be the Hecke algebra generated by all Hecke operators acting on \( \mathcal{M}_{\mathfrak{p}} \). For a prime \( \mathfrak{l} \) of \( A \), let \( \mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{l} = A/\mathfrak{l} \) and \( \mathcal{M}_{\mathfrak{p}}(\mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{l}) = \mathcal{M}_\mathfrak{p}\otimes_{A[1/\mathfrak{p}]} \mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{l} \). By extending the results of Section 4.1, any \( f \in \mathcal{M}_{\mathfrak{p}}(\mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{l}) \) has an expansion at the cusp \( [\infty] \) of the form \( \sum_{i\geq 0} b_i(f) t^{1+i(q-1)} \) with coefficients \( b_i(f) \in \mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{l} \). In the Hecke algebra \( \mathbb{T}_{\mathfrak{p}} \), let \( I_e \) (resp. \( \widetilde{I_e} \)) be the the ideal which annihilates the analogue of the winding element (resp. the winding element modulo the characteristic of \( F \)); see [e78] for the definitions. Let \( \mathcal{M}_{\mathfrak{p}}(\mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{l})[\widetilde{I_e}] \) be the subspace of \( \mathcal{M}_{\mathfrak{p}}(\mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{l}) \) annihilated by \( \widetilde{I_e} \).

- a saturated ideal \( I \) of \( \mathbb{T}_{\mathfrak{p}} \), with annihilator denoted \( \hat{I} \), satisfying \( I_e \subset I \subset \tilde{I_e} \) and \( \hat{I} + \tilde{I_e} = \mathbb{T}_{\mathfrak{p}} \);

- a prime \( \mathfrak{l} \) of \( A \) of degree 1 such that the \( \mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{l} \)-linear map \[ (\mathbb{T}_{\mathfrak{p}}/\tilde{I_e}) \otimes_{\mathbb{Z}} \mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{l} \longrightarrow \operatorname{Hom}(\mathcal{M}_{\mathfrak{p}}(\mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{l})[\tilde{I_e}], \mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{l}), \] which maps \( u \in \mathbb{T}_{\mathfrak{p}} \) to the linear form \( f \mapsto b_1(f|u) \), is an isomorphism.

Then:

- If \( \deg \mathfrak{p} \geq \max(q + 1, 5) \), the curve \( Y_1(\mathfrak{p}) \) has no \( L \)-rational points for any extension \( L/F \) of degree less than or equal to \( q \).

- Conjecture TDM is true for the ideal \( \mathfrak{p} \), namely \( Y_1(\mathfrak{p}) \) has no \( F \)-rational points.

The assumption in (i) on the existence of the ideal \( I \) is likely of a technical nature. The assumption in (ii) is deeper: it is related to complications that arise when adapting Mazur’s formal immersion argument to the Drinfeld setting. This will be discussed in Section 5.2.

5.2. Outline of the proofs

Schweizer’s uniform bound for the \( \mathfrak{p} \)-primary torsion, Theorem 5.3, is an analogue of a theorem of Kamienny and Mazur [e36], itself a stronger version of Manin’s theorem [e5] for the \( p \)-primary part of the torsion of elliptic curves over \( \mathbb{Q} \). The proof of Schweizer, after Poonen [e51], follows the same approach. The key ingredient essentially states that for any curve \( C \) over a global field \( K \), the \( d \)-fold symmetric power \( C^{(d)} \) has only finitely many \( K \)-rational points if \( C \) does not admit a \( K \)-rational covering of \( \mathbb{P}^1_{K} \) of degree \( \leq 2d \). When \( K \) is a number field, this is a theorem of Frey which derives from Faltings’ theorem on rational points of subvarieties of abelian varieties. When \( K \) is a function field, Schweizer has obtained a similar criterion from the Mordell–Lang conjecture for abelian varieties over function fields, proved by Hrushovski [e46]. He applied it to the Drinfeld modular curves \( X_0(\mathfrak{p}^e) \) for primes \( \mathfrak{p} \) to obtain Theorem 5.3.

To discuss the proofs of Theorems 5.7, 5.8, 5.11 and 5.12, we need to recall Mazur’s approach from [e14] for the study of \( \mathbb{Q} \)-rational points on the classical modular curve \( X_0(p) \), \( p \) prime (see also [e106] in this volume and the overview [e39] for additional details). Handling points defined over a number field \( K \) of degree \( d \) requires Kamienny’s generalized approach using the \( d \)-fold symmetric power of \( X_0(p) \). For simplicity we focus here only on \( d=1 \).

Let \( P=(E,C_p) \in X_0(p)(\mathbb{Q}) \) be a noncuspidal point for a prime number \( p \). Assume that the genus of \( X_0(p) \) is positive. The objective of Mazur’s formal immersion argument is to prove that the elliptic curve \( E \) has potentially good reduction at all primes \( \ell\neq \{2, p\} \); see Corollary 4.4 in [e14]. Consider the Abel–Jacobi map \[ \begin{array}{rcl} X_0(p) & \longrightarrow & J_0(p) \\ Q & \longmapsto & (Q)-(\infty)\end{array} \] where \( J_0(p) \) is the Jacobian variety of \( X_0(p) \). The main ingredient is an optimal quotient \( A \) of \( J_0(p) \) defined over \( \mathbb{Q} \) which satisfies the following two properties:

- The Mordell–Weil group \( A(\mathbb{Q}) \) is finite.

- Let \( \varphi:X_0(p) \to J_0(p) \to A \), which extends over \( \mathbb{Z} \) to \( \varphi:X_0(p)_{\mathrm{sm}} \to \mathcal{A} \), where \( X_0(p)_{\mathrm{sm}} \) is the largest open subset of \( X_0(p) \) smooth over \( \mathbb{Z} \) and \( \mathcal{A} \) is the Néron model of \( A \) over \( \mathbb{Z} \). When looking at the fibers at any prime \( \ell \) such that \( \ell \nmid 2p \), the map \( \varphi_{\ell} : X_0(p)_{\mathbb{F}_\ell} \to \mathcal{A}_{\mathbb{F}_\ell} \) is a formal immersion along the cuspidal section \( [\infty] \).

Optimal quotients satisfying (1) exist: the idea is to construct them with the property that their Hasse–Weil \( L \)-function does not vanish at the central value and deduce that their Mordell–Weil group is finite, in the spirit of the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture. For \( A \), one may take Mazur’s Eisenstein quotient [e13] or Merel’s winding quotient [e45] (the latter one being the largest quotient of \( J_0(p) \) satisfying this property).

Condition (2) is equivalent to the surjectivity of the induced map \( \varphi_{\ell}^*:\mathrm{Cot}_0(A_{\mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{l}}) \to \mathrm{Cot}_\infty(X_0(p)_{\mathbb{F}_\ell}) \) on the cotangent spaces, which in this case is equivalent to \( \varphi_{\ell}^* \) being nonzero. It is instructive to reformulate this condition for the Abel–Jacobi map \( X_0(p)_{\mathrm{sm}} \to \mathcal{J}_0(p) \) over \( \mathbb{Z} \) in terms of \( q \)-expansions of cusps forms: on the cotangent spaces at \( [\infty] \), it is simply the map \[ \begin{array}{ccc} S_2(\Gamma_0(p),\mathbb{Z}) & \longrightarrow & \mathbb{Z} \\ \sum_{n\geq 1} a_n q^n & \longmapsto & a_1 \end{array} \] where \( S_2(\Gamma_0(p),\mathbb{Z}) \) is the space of cusp forms of weight 2 with coefficients in \( \mathbb{Z} \). This map is nonzero, as a consequence of the classical formula \begin{equation}\label{eq-a1Tnf} a_n(f)=a_1(f|T_n),\quad \text{for all } n\geq 1, \tag{5.1} \end{equation} for the action of the Hecke operators \( (T_n)_{n\geq 1} \) on cusp forms. For the map \( \varphi_{\ell}^* \), there is a similar description involving cusp forms annihilated by the Eisenstein ideal, resp. the winding ideal of the Hecke algebra. One then uses a Hecke eigenvector in \( \mathrm{Cot}_0(A_{\mathbb{F}_\mathfrak{l}}) \), which necessarily has \( a_1\neq 0 \). This ensures Condition (2) is satisfied.

Using (1) and (2), Mazur was able to prove that the elliptic curve \( E \) necessarily has potentially good reduction at all primes \( \ell \neq \{2,p\} \) as follows. If \( E \) has potentially multiplicative reduction at \( \ell \), the point \( P \) will specialize on \( X_0(p) \) at \( \ell \) to one of the cusps. By applying the Atkin–Lehner involution \( w_p \), we may assume that it specializes to \( [\infty] \), therefore the point \( \varphi(P) \) specializes to 0 at \( \ell \). By the formal immersion property (2) for \( \varphi \) at \( \ell \), we also have \( \varphi(P)\neq 0 \). By (1) we also know that \( \varphi(P) \) is a torsion point. This contradicts a specialization lemma for points of finite order in group schemes.

The last part of Mazur’s proofs of Conjectures TEC and TEC\( ^+ \) is to discard the cases where \( E \) does not have potentially good reduction at \( \ell \) when \( p \) is large enough. If the point \( P \) on \( X_0(p) \) comes from a torsion point of order \( p \) on \( E \), this follows from known bounds for the order of the specialization of a torsion point at a prime \( \ell \) with \( p \neq \ell \), when \( E \) has good or additive reduction at \( \ell \). If \( P \) comes from a rational cyclic subgroup \( C_p \) of order \( p \), Mazur studies the isogeny character, i.e., the representation \( \operatorname{Gal}(\mathbb{Q}^\mathrm{alg}/\mathbb{Q}) \to \mathrm{GL}_1(\mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z}) \) coming from the natural Galois action on \( C_p \). Constraints coming from the existence of this isogeny character with the Riemann hypothesis for the reduction of \( E \) modulo \( \ell \notin\{ 2,p \} \) ultimately provide a finite list of possible values for \( p \).