by Richard Palais

My origin (1931–1943)

According to what my parents told my siblings and me, our family’s origin goes back to the 1890s when our four grandparents emigrated to the US. All were “Litvaks”, that is, Ashkenazi Jews who grew up in the shtetls near Vilnius in Lithuania, or, as I told my three children, they all came from “Fiddler on the Roof” country. Fortunately my father was admitted to Harvard in 1916, about six years before strict “Jewish quotas” were implemented.

When I was about four years old we moved from my birth town, Salem, famous for its “witches”, to Newton. There I went to the Angier Elementary School and to Warren Junior High, and then we moved again to Brookline where I went to eighth grade and the first year of high school before transferring to Governor Dummer Academy for the final three years of high school.

Junior and senior high school period (1943–1948)

When I was about twelve, I became interested in physics, and somehow came across a book titled The Einstein theory of relativity by Lieber and Lieber.1 It made a really profound impression on me. I pretty well understood and was fascinated by the central physical ideas; these were presented in a clear and elementary way. But I also very much wanted to understand the math details, to which the book had a pretty good but rather incomplete introduction. This started me on a long adventure. I recall starting out by reading the Britannica article on “Infinitesimal Calculus”, and after many intermediate steps, eventually reading and partially understanding Eddington’s The Mathematical Theory of Relativity.2 In any case a side result was that I became far ahead of my classmates in mathematical sophistication during my high school years (and got an 800 on my Math College Board exam).

Harvard undergraduate years (1949–1952)

Freshman year (1948–1949)

Upperclassman years (1949–1952)

In the late 1940s S.-S. Chern came to the US from China, visiting first at the Institute for Advance Study (IAS), and then in 1950 André Weil offered him a position at the University of Chicago Math Department, where Chern went the next year, after first spending the fall semester of 1951 as a visiting professor at Harvard. This turned out to be a very fortunate happenstance for me: Since no one in the Harvard Math Department was an expert in the Riemannian geometry of Lorentzian 4-manifolds, which my senior thesis was based on, Mackey asked Chern if he would be willing to look at my work. Not only did he read my draft, but he then asked me to come talk with him, and he gave me some valuable suggestions. He was apparently impressed enough with me that when George Mackey informed him in June of 1956 that I had just received my PhD and was looking for a position the following academic year, Chern arranged for me to have a two-year position at the University of Chicago, which then had one of the most outstanding math departments in the US. Chern was of course a mentor during those two years and we became even closer friends. In later years, I ended up spending more time with him, as a visitor to the UC Berkeley department, as a member of MSRI the first year after Chern founded it, and later still with visits to his Institute in Tianjin, together with Chuu-Lian Terng, who had her first postdoctoral position at Berkeley, thanks also to Chern. (She, like me, became close friends with Chern and his wife, and in 1996 Chern asked Chuu-Lian and me to write a biography of him [6].)

Even with Chern and Mackey’s helpful guidance, my senior thesis required very hard work and concentration during my college years, and it paid off handsomely. I was one of the eight students in my class elected to Phi Beta Kappa in our junior year, and I graduated summa cum laude with highest honors in mathematics. Perhaps even more important for my development, I was awarded the Sheldon Traveling Fellowship of that year.

Sheldon Fellowship (1952–53)

I was introduced to the mathematics of Bourbaki in my undergraduate years at Harvard. I liked the special way they presented mathematics, and their work greatly influenced my later mathematical study and writing style. So I decided to go to Nancy, where the Bourbaki group met and worked, for the greater part of my fellowship. I had only an undergraduate education, could only audit courses, and I did not have much interaction with the faculty there. But I did meet and become friends with Grothendieck, who was finishing his PhD. He later received a Fields Medal and one of the most influential mathematicians of the 20th century.

While in Nancy, I took several short side trips to the University of Strasbourg and across the border into Germany in order to fulfill the requirement of my fellowship not to spend too much time in one university or country.

During the time I was in Nancy, I also took several train trips to Paris, arriving at Gare d’Orsay. I stayed in the Latin Quarter, and loved walking around Paris. The station was later transformed into what became my favorite museum: Musée d’Orsay — just as Paris had by then become my favorite city.

While I was traveling on my fellowship, I felt that I should do mathematical research. The end result was my first published paper, “A definition of the exterior derivative in terms of Lie derivatives” [1].

Harvard graduate study years (1953–1956)

Looking back at how it happened, it seems almost accidental that I became Andy Gleason’s first PhD student — and David Hilbert was partly responsible. As an undergraduate at Harvard I had developed a very close mentoring relationship with George Mackey, then a resident tutor in my dorm, Kirkland House. Besides having meals with him several times each week, I took many of his courses. So, when I returned in 1953 as a graduate student, it was natural for me to ask Mackey to be my thesis advisor. When he inquired what I would like to work on for my thesis research, my first suggestion turned out to be something he had thought about himself, and he was able to convince me quickly that it was unsuitably difficult for a thesis topic. A few days later I came back and told him I would like to work on reformulating the classical Lie theory of germs of Lie groups acting locally on manifolds as a rigorous modern theory of full Lie groups acting globally. Fine, he said, but then explained that the local expert on such matters was a brilliant young former Junior Fellow named Andy Gleason who had just joined the Harvard Math Department. Only a year before he had played a major role in solving Hilbert’s Fifth Problem, which was closely related to what I wanted to work on, so he would be an ideal person to direct my research. I felt a little unhappy at being cast off like that by Mackey, but of course I knew perfectly well who Gleason was, and I had to admit that George had a point.

Andy was already famous for being able to think complicated problems through to a solution incredibly fast. “Johnny” von Neumann had a similar reputation, and since this was the year that High Noon came out, I recall jokes about having a mathematical shoot out: Andy vs. Johnny solving math problems with blazing speed at the OK Corral. In any case, it was with considerable trepidation that I went to see Andy for the first time. Totally unnecessary! In our sessions together I never felt put down. It is true that occasionally when I was telling him about some progress I had made since our previous discussion, part way through my explanation Andy would see the crux of what I had done and say something like, “Oh! I see. Very nice! And then…,” and in a matter of minutes he would reconstruct (often with improvements) what had taken me hours to figure out. But it never felt like he was acting superior. On the contrary, he always made me feel that we were colleagues, collaborating to discover the way forward. It was just that when he saw his way to a solution of one problem, he liked to work quickly through it and then go on to the next problem. Working together with such a mathematical powerhouse put pressure on me to perform at a top level, and it was sure a good way to learn humility! My apprenticeship wasn’t over when my thesis was done. I remember that shortly after I had finished, Andy said to me, “You know, some of the ideas in your thesis are related to some ideas I had a few years back. Let me tell you about them, and perhaps we can write a joint paper.” The ideas in that paper were in large part his, but on the other hand I did most of the writing, and in the process of correcting my attempts, he taught me a lot about how to write a good journal article. But it was only years later that I fully appreciated just how much I had taken away from those years working under Andy. I was very fortunate to have many excellent students do their graduate research with me over the years, and often as I worked together with them I could see myself behaving in some way that I had learned to admire from my own experience working together with Andy.

Let me finish with one more anecdote. It concerns my favorite of all of Andy’s theorems, his elegant classification of the measures on the lattice of subspaces of a Hilbert space. Andy was writing up his results during the 1955–56 academic year, as I was writing up my thesis, and he gave me a draft copy of his paper to read. I found the result fascinating, and even contributed a minor improvement to the proof, as Andy was kind enough to footnote in the published article. When I arrived at the University of Chicago for my first position the next year, Andy’s paper was not yet published, but word of it had gotten around, and there was a lot of interest in hearing the details. So when I let on that I was familiar with the proof, Irving Kaplansky asked me to give a talk on it in his Analysis Seminar. I’ll never forget walking into the room where I was to lecture and seeing Ed Spanier, Marshall Stone, Saunders Mac Lane, André Weil, Kaplansky and Chern all looking up at me. It was pretty intimidating and I was suitably nervous! But the paper was so elegant and clear that it was an absolute breeze to lecture on it, so all went well, and this “inaugural lecture” helped me get off to a good start in my academic career.

My first academic position at the University of Chicago (1956–58)

After receiving my PhD degree from Harvard, I applied for my first academic position to several distinguished Mathematics Departments. In particular, Professor Chern of University of Chicago encouraged me to apply there, and I am pretty sure he played an important role in getting me an offer there. That department was a powerhouse then with Shiing-Shen Chern, André Weil, Antoni Zygmund, and Saunders Mac Lane as senior faculty, and Paul Halmos, Irving Segal, and Edwin Spanier as assistant professors. Steve Smale and Siggy Helgason were also beginning instructors there and we three became life-long good friends.

I was supposed to be in Chicago for the fall quarter, but since my first child, Julie, was born in September, I received the Department’s permission to start in the winter quarter. Julie had a long career as a polar glaciologist and made important contributions to climate change research, studying volcanic fallout in ice cores from both Greenland and Antarctica. She served as the Program Director of the Antarctic Glaciology Program at the National Science Foundation (NSF) from 1990 to 2016. Both the Palais Glacier and Palais Bluff in Antarctica were named in her honor, and she received the Explorers Club Lowell Thomas Award in 2007 for her work in climate change research. She also received an honorary degree from the University of New Hampshire, and the Goldthwait Polar Medal from the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center at The Ohio State University in 2019.

The first day there while setting up my office, Chairman Mac Lane came in and said “Good to see you,” and with a big smile and a pat on my back said “We liked the work you have been doing so much, we will raise your annual salary from \$5,000 to \$5,500.”

One piece of research I accomplished at Chicago was the equivariant embedding theorem for \( G \)-manifolds, a result which was also independently discovered by Mostow at Yale. We each published our individual paper with no claim to priority and remained friendly. This theorem has become known as The Mostow–Palais Theorem.

Institute for Advanced Study (1958–60)

After two years at the University of Chicago, I felt honored to receive a two-year membership at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton. Among the esteemed faculty were Armand Borel and Deane Montgomery, both leading experts in the theory of transformation groups, which was also my research focus. They conducted a seminar on this subject that ultimately served as the foundation for a book published in the Annals of Mathematics. As a young member, I actively participated in the seminar and contributed a chapter to the book [e1].

The IAS director, J. Robert Oppenheimer, held private meetings with each new member and occasionally invited a select group of us to his home for dinner. I fondly recall Montgomery inviting me to dinner at Chung-Tao Yang’s house, where I met Yang’s son Deane, who was just a baby at the time. Deane Yang is now a professor of mathematics at New York University’s Courant Institute of Mathematics.

During my time at IAS, my son Robert was born in Princeton, and he has since become a mathematician at the University of Utah, specializing in the intersection of genetics and mathematics. He received patents for methods that have been widely used for newborn screening and in rapid tests for infectious diseases such as Covid, and with me and H. Karcher for mathematical visualization tools. He is also a very good rock climber (and has climbed El Capitan five times).

Many young IAS members had offices in the famous Electronic Computer Project (ECP) building, which housed the von Neumann computer. Notable young members like Michael Atiyah, Fritz Hirzebruch, Steve Smale, and Moe Hirsch were also part of the vibrant community during that period. Members lived in on-campus housing, had regular lunch at the dining room, and daily tea time (4 p.m.) with fresh baked cookies. It was a wonderful place to be for mathematical collaborations and friendships.

Brandeis University (1960–62)

I was thrilled to secure a tenure-track position at Brandeis University in Waltham, a suburb of Boston, where my family — parents, brothers, and a sister — were all nearby (as were Harvard and MIT). Named after Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, the first Jewish justice, the University was established by the Jewish community in 1948. While I may not have been religious, I certainly felt a strong ethnic connection to my Jewish heritage.

When I joined the faculty, Arnold Shapiro served as the Chair, and I was welcomed by colleagues such as Maurice Auslander and Edgar Brown. Around the same time, David Buchsbaum, Harold Levine, Jerry Levine, Teruhisa Matsusaka and Robert Seeley joined the department, followed later by Paul Monsky, Alan Mayer, and David Eisenbud in the 60s. Most of my colleagues were of similar age, fostering a friendly atmosphere where we often enjoyed lunch together at the Faculty Club. It was an energetic and vibrant department, and we had a great time developing both the undergraduate and graduate programs. Since several of us had connections to the University of Chicago, where instructors were invited to department meetings, we modeled our own department after the one in Chicago.

Seminar on the Atiyah–Singer Index Theorem (1962–63)

I had the privilege of being friends with Fritz Hirzebruch, the visionary behind the Arbeitstagung (annual mathematics meeting in Bonn). The meeting introduced a unique approach: rather than having a preset agenda, the program was shaped collaboratively by the participants through open discussions. This innovative format ensured that the talks highlighted the latest advancements in mathematics, allowing many significant results to be unveiled for the first time at the conference. The papers featured in this conference, authored by leading mathematicians, explored a diverse array of topics, including algebraic geometry, topology, analysis, operator theory, and representation theory. They collectively showcased the impressive breadth and depth of pure mathematics that has consistently defined the Arbeitstagung. I attended this gathering nearly every year for many years.

In 1962, Atiyah provided a thorough explanation of the proof of the Atiyah–Singer Index Theorem at the Arbeitstagung. As I exited the lecture hall, Borel remarked on the success of our seminar on transformation group theory at IAS in 1959 and proposed that we conduct a seminar on the Atiyah–Singer Index Theorem together. I requested a leave of absence from Brandeis to spend the fall semester at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS). However, in the middle of summer, Borel informed me that he would need to be in France for the first semester. He offered to assist in organizing and outlining the seminar, leaving me to manage it independently. The seminar turned out to be a success, featuring engaging weekly lectures. I subsequently compiled the lectures into a book titled Seminar on the Atiyah–Singer Index Theorem [2].

My youngest child David was born in April 1963. He obtained a PhD degree in geology from the Arizona State University at Tempe, did two years of postdoctoral research, then went to work Arrowhead water company for a number of years, and now is the Primo Water Corporation’s manager for the western US. While he was a graduate student, he went to Antarctica to do research while his sister Julie was there, too. It is probably quite unusual to have siblings in Antarctica for research at the same time.

My ex-wife Ellie and I were very lucky to have three wonderful children, all had PhD degrees, good jobs, and happy families.

Brandeis and UCI (1962–)

The launch of Sputnik by the Soviet Union in 1957 prompted the U.S. government to increase funding for scientific research. Representatives from the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Department of Defense (DOD) visited our department to encourage us to submit grant proposals. I wrote a short proposal every three years detailing my past work and future plans. For mathematicians of my generation, there was relatively little effort needed to secure grants, as long as we maintained a reasonable level of research output.

The Brandeis Department functioned smoothly and amicably overall, though I did have a couple of disagreements with my colleagues. One was regarding the tenure decision for Michael Spivak. He was an outstanding teacher and communicator, and I believed that while his research may not have been particularly strong, his teaching and contributions to educational resources made him an excellent candidate for tenure in an undergraduate program. Another contentious tenure decision involved Mike Shub, a remarkable researcher in dynamical systems. Many of my colleagues opposed his tenure because he had supported students protesting the Vietnam War and helped prevent their draft by refusing to give them failing grades.

In 1995, Brandeis University offered early retirement incentives: faculty could retire in 1997 with 90% of their pay and reduced teaching responsibilities. Since I would turn 66 that year in 1997 and wanted to devote more time to mathematical visualization programs in collaboration with Hermann Karcher, I decided to accept the offer. I continued to teach one course per year at Brandeis from 1997 to 2003, when my wife, Chuu-Lian Terng, received an offer from the University of California, Irvine (UCI). We moved to Irvine in 2004, where I continued to work on my mathematical visualization projects, engage in mathematical research, and teach one course per year at UCI until 2009.

My graduate students

I enjoyed working with graduate students, often feeling I learned as much from them as they did from me. Many of my PhD students went on to pursue academic careers, while others have found success in high-tech and financial industries. It has been a great pleasure of my life to maintain connections with many of them, who continue to visit me from time to time. I take pride in all my graduate students, and would like to highlight three of them here.

Karen Uhlenbeck received her Ph.D. in 1968 and is now a professor emeritus of mathematics at the University of Texas at Austin, as well as a distinguished visiting professor at the Institute for Advanced Study. In 2019, she was awarded the prestigious Abel Prize for her pioneering contributions to geometric partial differential equations, gauge theory, and integrable systems, which have had a profound impact on analysis, geometry, and mathematical physics. Notably, she is the first and, thus far, only woman to receive this honor since the prize’s inception in 2003. Demonstrating her commitment to advancing the field, she generously donated half of her prize money to organizations that promote greater engagement by women in research mathematics.

Leslie Lamport earned his PhD in mathematics in 1972. He is renowned for his groundbreaking work in distributed systems and is the original developer of the \( \mathrm{\LaTeX} \) document preparation system, for which he authored the first manual. In recognition of his significant contributions, Lamport was awarded the 2013 Turing Award for establishing clear and coherent frameworks within the often chaotic realm of distributed computing systems, where multiple autonomous computers communicate via message passing. His development of important algorithms and formal modeling and verification protocols has greatly enhanced the correctness, performance, and reliability of computer systems.

Bing-Le Wu is a partner at Capula Investment Management LLP, one of Europe’s largest hedge funds, with approximately \$30 billion in assets under management as of 2024. Since 2020, Bing-Le has served as a Trustee at Brandeis University and generously established the endowed Richard Palais Graduate Fellowship for the Brandeis Mathematics Department, demonstrating his commitment to supporting future generations of mathematicians.

I feel grateful for the opportunity to mentor such talented students and to witness their remarkable achievements in their respective fields.

Some of my research (1962–)

Morse theory on Hilbert manifolds and the Palais–Smale Condition C

Someone told me after listening to my lecture on “Morse Theory on Hilbert Manifolds” at the Harvard topology seminar that he just heard a talk very similar to mine by Steve Smale at Columbia. I wrote to Smale and we realized that we had very similar results. In fact, we each give three of the same conditions (a), (b), (c) for a function on Hilbert manifolds that our Morse theory would work for, and the third one is the essential one and later was known as Condition C or the Palais–Smale Condition C. We decided to publish a joint announcement in the Bulletin of the AMS and to publish our individual papers separately. Communication was so different in the old days; we relied on regular mails and priority fights were uncommon.

The principle of symmetric criticality (1979)

The original proof of Schwarzchild’s solution of the Einstein equations was very long, but an alternate proof by Hermann Weyl was short and elegant: He varied the Hilbert–Einstein functional on the set of the metrics invariant under SO(3). Since such metrics only depend on the radius, the Euler–Lagrange equation becomes an ordinary differential equation, which allowed him to write down the explicit solution. In other words, he stated that if a function \( f \) is invariant under a group, then to find a critical point of \( f \) that is fixed by \( G \), we only need to find critical points of the restriction of \( f \) to the set of fixed points of \( G \). I found that this was not always true, but it is true if the group or the isotropy subgroup of the action is compact, which is the case for a lot of applications in geometry and physics. I wrote up the paper [3] and submitted it to the editor (Sydney Coleman, a physicist at Harvard) of the Communications of Mathematical Physics. The paper was accepted right away and Coleman told me that he was surprised this principle may not always work. This has become one of my most quoted papers.

The geometrization of physics (1981)

I went to Taiwan with my wife Chuu-Lian Terng in the summer of 1981 and gave a summer course on mathematical physics at National Tsing-Hua University in Taiwan. I wrote up my lecture notes and it was published there [4].

A general canonical form theory (1991)

Around 1982, I was working on polar actions, that is, isometric actions on a Riemannian manifold that admit a section (a closed submanifold that meets all orbits and meets them orthogonally). A typical example is the action of SO\( (n) \) on the space of \( n\times n \) symmetric real matrices by conjugation, and the set of diagonal matrices is a section. Chuu-Lian was reading a paper by Carter and West that studied codimension 2 isoparametric submanifolds of spheres, and tried to find the theory for any codimension. She realized that principal orbits of polar actions on spheres are the homogeneous isoparametric submanifolds in spheres. So we worked out a structure theory of polar actions and Chuu-Lian developed the theory of isoparametric submanifolds in space forms. Gudlaugur Thorbergsson and Enrst Heintze joined us to develop a theory of hyperpolar actions in the 1990s.

Critical point theory and submanifold geometry (1987)

Shiing-Shen Chern invited Chuu-Lian and me to give two summer courses at Nankai Institute in Tianjin, China, in 1987. We each gave a one-month “mini course”. Chern was trying to help build mathematical research in China after the Cultural Revolution by inviting western mathematicians to go to China for conferences or to give mini courses. Nankai would get students from many different universities to attend these courses. Chuu-Lian gave a course on isoparametric theory and I gave a course on Morse theory. We spent one semester to write up the lectures we gave there as the book Critical Point Theory and Submanifold Geometry [5].

Symmetries of solitons (1997)

I liked the results in the paper “Poisson actions and scattering theory for integrable systems” by Chuu-Lian Terng and Karen Uhlenbeck [e2]. In this paper, they explain the commuting Hamiltonian flows, the scattering and the inverse scattering theory of soliton equations in terms of group actions. When we visited the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in Bonn as members in 1997, I was invited to give a “mini course” at the University of Bonn. Since I liked the joint paper by Chuu-Lian and Karen, I worked very hard to give an introduction to the history of soliton theory and present their results on symmetries of solitons. This effort resulted in the paper “The symmetries of solitons” [7]. Chuu-Lian and Karen commented that it was such a nice presentation that people might read my paper instead of theirs.

Visualization of mathematics

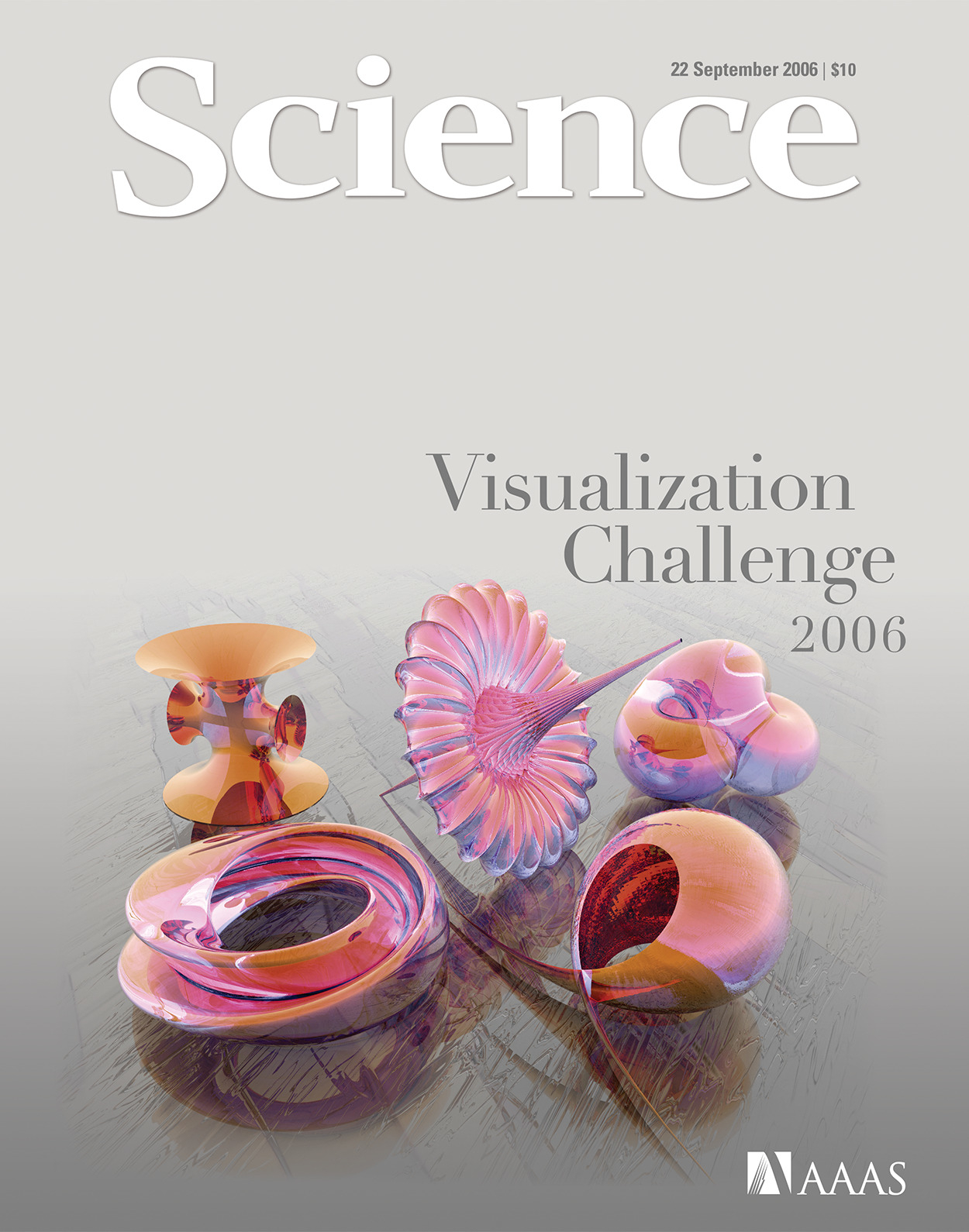

In the later years of my career, I developed a strong interest in mathematical visualization, and created a program called 3D-XplorMath. This is a tool for aiding in the visualization of a wide variety of mathematical objects and processes. Based on what I learned from my experience in writing this program, I wrote an essay called “The visualization of mathematics: Towards a mathematical exploratorium” [8]. Hermann Karcher worked jointly with me on developing 3D-XplorMath (3d-xplormath.org) and the Virtual Math Museum (virtualmathmuseum.org). Science magazine ran a yearly visualization challenge (cosponsored by the NSF) which graphic artist Luc Bernard and I jointly won in 2006 (the first year of this challenge). Our winning visualization was displayed on the cover of an issue of Science (see Figure 1).