by Allyn Jackson

Ruth J. Williams is one of the world’s leading probabilists. Her work combines a penchant for applied problems with a love of rigorous theoretical development. Much of her research has trained her formidable technical prowess on mathematical questions arising in the dynamics of stochastic models of complex networks. Her work helped to build and expand the theoretical foundations for reflecting diffusion processes, particularly reflecting Brownian motions. She has developed fluid and diffusion approximations for the analysis and control of general stochastic networks and has brought systematic approaches to proving heavy traffic limit theorems. Her most current work, in collaboration with systems biologists, centers on stochastic models for epigenetic cell memory.

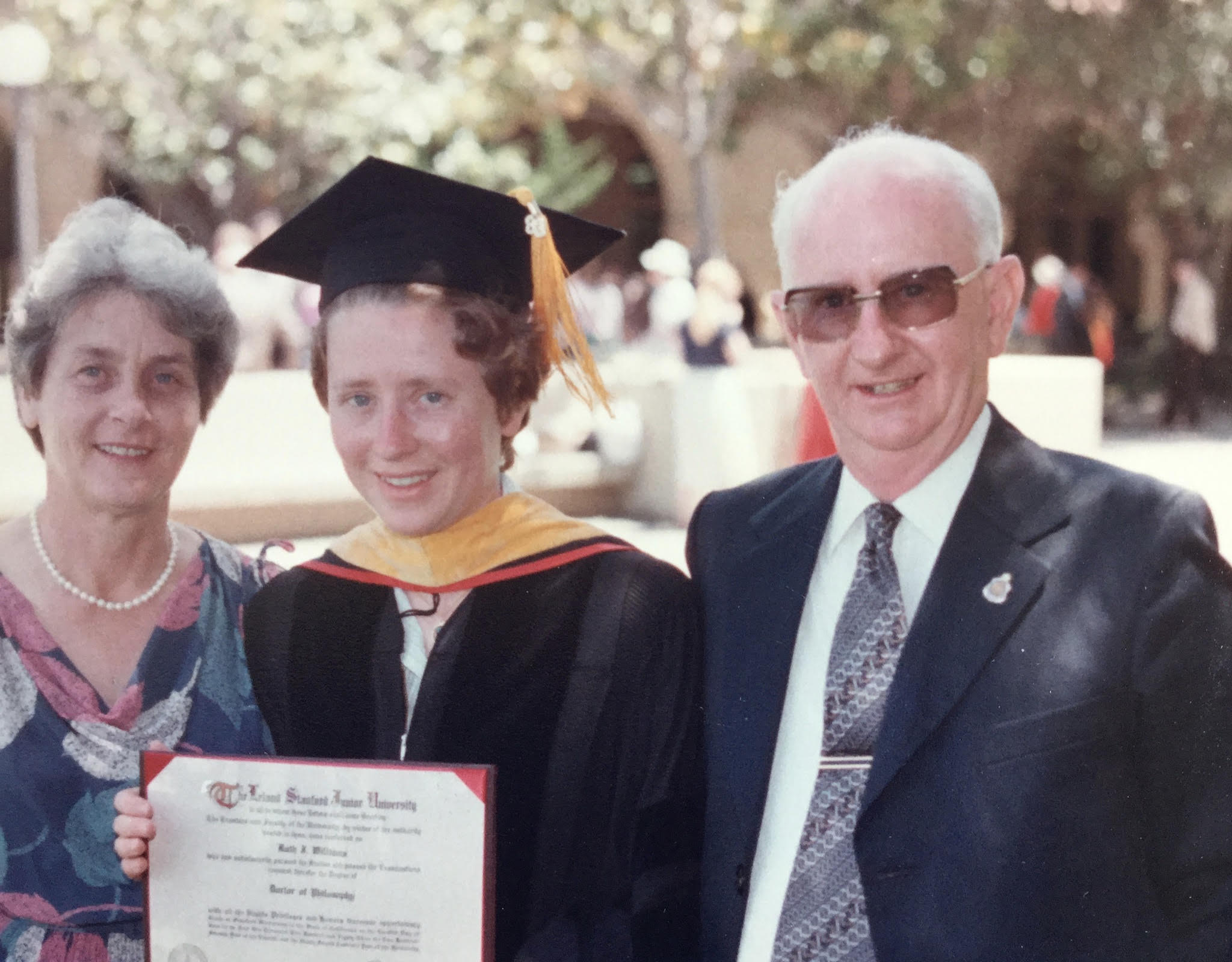

Born in Australia, Williams completed a Bachelor of Science (Honors) degree in mathematics in 1976 at the University of Melbourne. She also earned a Master of Science degree there in 1978 before moving to the United States to attend Stanford University, where she earned her PhD in 1983 under the direction of Kai Lai Chung.

After a postdoctoral position at the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences at New York University, she joined the faculty of the University of California at San Diego (UCSD), where she is now Distinguished Professor of the Graduate Division, Distinguished Professor of Mathematics Emerita, and former holder of the Charles Lee Powell Chair in Mathematics I.

Williams received a National Science Foundation Presidential Young Investigator Award in 1987 and an Alfred P. Sloan Fellowship the following year. The Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS) awarded her both the 2016 John von Neumann Theory Prize (jointly with her collaborator Martin Reiman) and the 2017 Award for the Advancement of Women in Operations Research and the Management Sciences. Williams was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2009, to the US National Academy of Sciences in 2012, and as a Corresponding Member of the Australian Academy of Science in 2018.

What follows is an edited version of an interview with Ruth Williams that took place over two sessions in June 2024.

“Your computer for 20 cents”

To start at the beginning — can you tell me about your childhood growing up in Australia?

I was born in Melbourne, which is the capital city of Victoria, one of the southern states in Australia. When I was in grade three, we moved to an inland city called Bendigo, about 100 miles north of Melbourne. That’s where I spent most of my childhood. We moved because of my father’s job. He originally worked for the federal government, the Australian Public Service, in Melbourne. When we moved to Bendigo, he became head of business studies at the local technical college, the Bendigo Institute of Technology.

What was his background?

He grew up in the depression years and originally worked for the post office in accounting, I think. He was also studying commerce part-time at the University of Melbourne. Then World War II came along, and he was an officer in the navy. After the war, he worked as an audit inspector for the navy and the federal government public service. He also went to night school to complete his Bachelor of Commerce degree at the University of Melbourne.

He studied accounting, so he must have been good at math.

I believe so. He was very logical and mathematically inclined. He was also visionary about computers in education. When he moved to the technical college in Bendigo, it was the early 1960s, and there were very few computers in education in Australia. He was very effective at getting mainframe computers for the college. That was a big deal. He also served on an Australia-wide committee, called a Commonwealth Committee, advising about computers in education. He made a couple of overseas trips for that committee, in 1968 and 1972, to look at how computers were used in education around the world. I remember those trips. He was away for — it must have been three or four months at a time. Travel in those days took longer and was very expensive. Once one was overseas, one made the most of it.

Where did he travel to?

He went largely to the US, Canada, and the UK. He wrote extensive reports; I still have one of them. He helped bring computers into education in Australia, especially in Bendigo, and also made strong connections to industry as well as to the local high schools. He started a computer club for high school students with the slogan, “Your Computer for 20 Cents.” It was 20 cents a year to join the computer club, and you could submit as many computer jobs as you wanted to the mainframe computer — but the maximum number of runs you could get per day was one! That was a really great thing. I got to see early on how computers could be a very useful tool.

There is a picture of three girls, including you, who were members of the Bendigo Computer Club. That was the club your father put together?

Yes. There were many more members of the club; only three are in the photo. Initially there were programming classes on Saturday morning where anybody from the Bendigo community could go. Quite a few teachers from local high schools went and learned a little bit of programming, and high school students too. Eventually I taught those classes as a member of the computer club. It was really a great thing.

What language did you program in?

Initially I wrote in FORTRAN, but I also wrote a few programs in ALGOL and COBOL. I wrote about 100 programs while I was in high school. They were batch jobs, so every time you made a mistake you had to wait a day to send in a corrected program. Access was via keypunch cards, which made it a long process. There were no terminals at that time, other than the one that was attached to the computer itself.

What were the programs you wrote? What problems were you working on?

I remember trying to write a program to classify plants, one to make a decision tree, one for airline reservations. There were other, simpler things like computing using some mathematical formulas. This was before there were hand-held calculators and the like.

So you were doing this in high school.

In my spare time!

And prior to that, did you always like mathematics? Did you have interests in other areas?

I liked mathematics and science equally well. I liked solving problems — understanding why things are true, working things out, as opposed to just memorizing them.

In mathematics you can understand things to the very bottom.

Yes. I really like to dig down and understand at a fundamental level. That’s one attraction of mathematics for me.

Did you have good math teachers?

Yes, I had a teacher in fifth and sixth grade — it was the same teacher for both — Mr. Davies, who really encouraged me in mathematics. I liked to always get things exactly right, and he encouraged that. Then in high school I had a number of math and science teachers who encouraged me, in chemistry, physics, and math. Some went out of their way to help; I had a chemistry teacher, Mr. Lake, who had me read ahead to the next year’s material.

Did you encounter the attitude that girls can’t do math and science?

I don’t think so. I had a strong support structure. I had parents and teachers who were very supportive of me.

Is there anything different about Australia that would make it more acceptable for girls to be interested in these subjects?

I’m not sure. I was good at mathematics, and people who were good at something were encouraged. I was always interested in having some kind of scientific career, which includes mathematics. I always felt like that was possible.

You didn’t feel there were obstacles, or that this was something strange for a girl to do. That’s great.

Well, there weren’t that many women I could name who had scientific careers! But I just felt that it was a natural thing that I was good at and enjoyed.

And your mother, did she have a profession also?

Yes, she was trained as a nurse. When she had children she stopped working, but as we got older, she went back to nursing. She became a nurse at a home for the aged blind in Bendigo, and eventually became director of nursing there. My mother was great. She was a very caring person and also was always very encouraging. I had great parents; I was very lucky.

And siblings?

I have a brother and a sister, both younger.

What did they end up doing?

My brother is an electrical engineer in Sydney. My sister lives in Bendigo, and she was a nurse — an operating theater nurse actually, which is an intense profession.

You have to have strong nerves for that! Did your brother get a PhD?

No, he earned a Bachelor of Science (Honors) degree, specializing in electrical engineering from the University of Melbourne. My sister trained as a nurse at the Royal Melbourne Hospital School of Nursing. Nursing was not a university degree at that time. Later she earned her Bachelor of Health Science in nursing from La Trobe University and took various postgraduate specialized training courses, for example, related to surgery.

Drilling down to understand things

It sounds like your parents had a huge positive influence on all three of you. After high school, you went to the University of Melbourne for your undergraduate studies. Was that the closest university to Bendigo?

The way it worked was that when you applied to go to university in Australia, you usually applied to the universities in your own state. It was difficult to go to a university in another state, other than maybe to the Australian National University, which is in Canberra, the capital of Australia. It would accept students from any state.

Melbourne was the best university in the state of Victoria. There were competitive statewide exams at the end of high school, exams in different subjects. That determined what universities you got admitted to. You could give a preference, but the exams gave you a ranking. Melbourne was the hardest one to get into.

Did you know what you wanted to study?

I knew I wanted to study science, but I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to do chemistry, physics, or mathematics. In the first year I studied all three — actually I studied two kinds of mathematics, pure and applied. At the end of the first year I needed to decide, and I decided to do mathematics. Again, it goes back to being able to drill down and understand why things were true. I felt it was a bit harder to do that with physics and chemistry. In chemistry, the model of the atom seemed to change every year, which was a little disturbing! Physics was closer to mathematics. I was good at all three, but I thought mathematics enabled me to understand things at a fundamental level and that you could do a lot of things with it.

I also informally minored in what would now be called computer science and was then called information science. So I took computing courses as well. That was easy to do.

You were already a hacker, right? So to speak!

I don’t think I was a hacker! In the first year, there was a little component of computer programming in an applied math course, and I found that pretty easy because I could already program, because of my experience with the Bendigo Computer Club. So then I was helping other students. But it got more interesting in later years. There were things that I hadn’t studied before, such as algorithms and data structures, and also different languages. I learned SNOBOL and Pascal at some point.

It’s often said today that girls go into computer courses lacking the kind of programming experience that boys are likelier to have. But at that time you were unusual even to have any programming experience at all.

That’s true. That was one of the lucky things about being in Bendigo, where there was the computer club that gave you access to a computer. At the time it was very unusual, especially in a regional city like Bendigo. Maybe it was a bit more common in Melbourne. There were a few students I ran into at university who had a bit of programming experience, but it was very unusual at that time to have that kind of access.

Those two girls in the photo from the Bendigo Computer Club — those were friends of yours?

Yes. We were all members of the computer club. I knew them pretty well.

Did they go on to do something in math or science?

I don’t know. They didn’t go to the University of Melbourne, and I lost track of them. There were some other people at the high school I went to who did go to the University of Melbourne. Since I was from the “country”, I couldn’t live at home to go to university, so I lived in a residential college, St. Hilda’s College. There were quite a few girls from my high school who also lived in St. Hilda’s College, so that was nice. And all of them were studying science. One of them, Sue Winzar, had been a member of the Bendigo Computer Club. Sue had a very successful career in IT, eventually heading up IT for Esso in Australia.

Did you have other interests as a young person, for example, music? Did you play a musical instrument?

I learned the recorder in primary school! I’m not really good at musical instruments. I like outdoor things, that’s my release.

Does that come from living in Australia?

I think so. I think that’s a part of the Australian spirit, to like to be outdoors. I played some tennis and did some running for a while. Also, my family would often spend weekends and holidays working at a wheat and sheep farm that we owned. This was another aspect of my love of the outdoors.

A wheat and sheep farm! Can you say more about that?

It was originally the farm that my mother had grown up on. Her sister and brother-in-law had owned it for a while, but then they moved into town, and we bought it from them when I was around five years old. It’s one of the reasons we moved from Melbourne to Bendigo, because it was closer to the farm. We would go there on the weekends. Farms always need something to be done! Wheat and sheep are good because they tend to look after themselves fairly well, but there were always things to be done, like mending fences and making sure water didn’t flow in the wrong places. Shearing time was a busy time, and we would help with rounding up the sheep and gathering wool from the shearing. I remember jumping on the wool bales to press them down. Feeding the shearers was a nonstop task because they consume a lot of energy.

Programming computers during the week and then going on the weekend into the country — that sounds like a great balance.

Yes, I think it was a great experience for me as a child. I have a lot of good memories from that.

Did you ever participate in math competitions when you were growing up in Australia?

No. I didn’t even know they existed — and I am not sure they did exist in Australia when I was a kid. But I did have one really nice experience when I was in the last year of high school. There was a conference in Melbourne celebrating Edison’s birthday, and they selected one student from each high school in the state of Victoria to go. And I was chosen to go from my high school. That was a really interesting experience. It was a few days in Melbourne, and people came to speak about the future of science. I got to meet other students from around the state of Victoria. Edison, of course, had been from the United States, so the conference had an international feel. I was very lucky to do that.

The speakers were from Australia?

Some of them were from overseas, but some were from Australia. I remember there were people who talked in particular about the future of computing.

A PhD, the next natural step

Going back to your time at the University of Melbourne, were there professors there who were special to you, who encouraged you?

Yes, especially as I got into my third year. In Australia, the regular bachelor’s degree was a three-year degree. Then you could do an honors year, if you got high enough marks, and would write an honors thesis as well as take some courses. So I did that. In my second and third years, I had taken a couple of courses in analysis from a professor, Jerry Koliha, and really liked them, so I chose to do my honors thesis with him on pseudo-inverses of operators. It’s part of functional analysis. I really liked his mathematical style. He was very precise but also very enthusiastic about mathematics. That was a good experience.

Then I stayed on to do a master’s degree, which at the University of Melbourne was purely by research. I did research in differential games, with David Wilson, which I also enjoyed.

What does that mean, differential games?

It’s game theory, but where the state of the system that you are looking at is dynamic. It’s governed by a differential equation. You have two or more players who have controls in those differential equations that can influence the behavior. A way to think about it is that with optimization or control, you have one player who’s trying to control the behavior of a differential equation. In differential games, you have more than one player, and they are competing against one another.

Differential games are used for modeling dynamic situations that arise in a whole host of applications. At the time there was a lot of interest in strategic applications, but today differential games are used in other areas, in engineering and even in data science.

Did you publish a paper about that research?

I published two papers.

That’s impressive. How did you come to the idea of going for a PhD in mathematics? Did you always have it in mind, or did your professors encourage you?

I think I always had it in mind as the next natural step. Certainly I had in my mind since I was an undergraduate that I would like to become a university professor. At the time, it was usual for Australian students who wanted to pursue a PhD to go overseas. Usually at that time people would go to the UK. I did apply to the UK, but I also applied to a couple of places in the US. Since I’d been doing research on differential games, I wanted to at least have the option of continuing that.

So I looked for places that had a strong mathematics department but where there was somebody doing differential games. I applied to both Stanford and Berkeley and got admitted to both. Stanford had someone in aeronautical engineering who did differential games. I got admitted to the math program, but I would have been able to work with that person if I’d wanted to. That’s how I chose Stanford. I could have gone to the UK, but if I wanted to continue doing differential games, it was a bit better to come to the US.

It’s definitely a different setup going to the US versus going to the UK. In the UK, you focus very quickly on what you want to pursue for your PhD, whereas in the US there is a lot more coursework first, and then you choose what you want to do. The Australian system is a lot like the British system. I feel like I got the best of both systems, because I got my early education in Australia and then I came to the US and got the benefits of graduate education here. It’s very easy here to pick up new subjects, because you can often just go and take a course.

Graduate school at Stanford

You knew you were going abroad and would leave your family. Was that difficult?

Especially at that time, when air travel was not so common, it was a big step. It was very expensive to travel back home, so I only went back a couple of times to Australia during my PhD. But people wrote letters in those days, so I would write a letter every week, and my parents would write a letter every week. We used aerogrammes, as they were less expensive than a letter in a separate envelope. Phone calls were also very expensive and only used rarely. As an international student, I did have a host family, the Richerts, who would invite me, together with some other Stanford graduate students, to events like Thanksgiving. That was a good way to experience American family life. The Richerts were very kind to me, and we have stayed in touch over the years.

Was there much of a culture shock to go to California, to a university that must have had a very different style and feel from Melbourne?

In some ways yes, although California is quite a bit like Australia, in terms of the vegetation and climate. I think the first thing that struck me was that the lectures in Australia were more formal than the lectures in the United States. At the time, there was not very much reliance on textbooks in Australia. A lecturer would write on the board very carefully, and you would take very careful notes. So I was used to learning just from whatever somebody presented in a lecture, rather than reading a textbook. I think that’s a good skill to have, to be able to take notes and listen well.

Of course, the system as I said is a bit different too, in that, for a PhD in Australia, once you start, you’ve already selected who you want to do your PhD with. The PhD was shorter, three years, because people were usually supported on fellowships. In the US in mathematics, people are most often supported on TAships [teaching assistantships]. I was fortunate for the first couple of years to have partial support from a scholarship from the University of Melbourne. That meant I didn’t have to TA quite as much in the first few years, though mainly I was supported by a TAship from Stanford. For the TAship, I largely had to teach my own courses, which had about thirty students. I was responsible for teaching the whole course, including grading and examinations. That was a very good experience.

At that time, in PhD programs in the US, there was coursework in the beginning that you didn’t have in Australia or Britain. I took probability courses from Kai Lai Chung and other people. One nice thing about Stanford was that there were people doing probability in different parts of the university. There were people in statistics, in operations research, even in the business school, who were doing applied probability, who were inventing new probability models and analyses.

My first year I took a game theory course as well, because I wasn’t sure if I still wanted to do differential games at that point. That was very interesting, because game theory was in the economics department. They had a summer program in game theory, and they selected me to write the notes from the course they were teaching. I got to meet some famous people in game theory, like Robert Aumann. That was pretty amazing. I wouldn’t have met those people in Australia. That’s one of the bonuses of having come to the US.

Eventually I decided to do probability rather than game theory. And being a probability student at Stanford was great, because there were lots of visitors coming through to give a talk or to stay for longer periods of time, and you got to meet luminaries in probability. It was an excellent place to be for that.

You and some other women PhD students took a reading course with Samuel Karlin. Can you tell me about that?

We were the three women out of about a dozen PhD students in my year. We had a lot of our initial classes together, but it also turned out that we were all interested in probability. I think we’d taken the basic graduate probability course together. Sam Karlin was writing a book on stochastic processes — actually a two-volume set — with Howard Taylor [of Cornell University]. Stochastic processes weren’t emphasized so much in the basic probability course, so we wanted to learn more about that. We asked Karlin if he would do a reading course with us.

The three of us would meet with him once a week and go over the reading we’d been doing and ask questions. There were some long chapters, including one of more than 100 pages on diffusion processes, and we worked our way through that. That was a great experience, both learning together — we would talk with one another about what we were reading — but also interacting with Sam Karlin. He was always very enthusiastic about whatever he was working on and would tell us about his research. I got to meet some of the people visiting Stanford who were working with him, like Simon Tavaré. There were always probability visitors coming through, either visiting Chung or Karlin, who were the two main probabilists in the mathematics department.

What was Karlin like as a person?

He was always very nice to us. He was very hard working and committed to what he was doing. You’d go into his office, and immediately he would start talking about math. He was so enthusiastic about it, it was infectious.

He was also very prolific. He started collaborating with biologists at some point in his career, so there were always a lot of people coming through, consulting with him about problems they needed to have solved. I remember him saying at one point that when he made the transition to working with biologists, he learned you needed to have experiments. I always remembered that, that it’s important to be connected to the experimental side of biology if you want to work with biologists.

We three women who were in the reading course all went into probability. I worked with Kai Lai Chung, Amy Rocha worked with Joe Keller, who had come fairly recently to Stanford, and Marge Foddy worked with Sam Karlin.

Three women out of an incoming class of about a dozen PhD students — that’s a large percentage of women.

It was a big percentage. In other years, there were no incoming women students. It was maybe a bit unusual. But it was good to have other women in the class, especially since we were all interested in probability.

Was it important to you that other women were there? Did you feel any of what has been called the “chilly climate” that women in PhD programs have sometimes felt — that they felt out of place or were not taken seriously?

I don’t think I really felt that, but it’s always good to not be too isolated. It was good that there were other women in the program. At that time, in science and engineering in general, there weren’t so many women. The Dean of Graduate Affairs, Jean Fetter, was cognizant of this, and organized the making of a little booklet about women in science and engineering at Stanford. In my final year, her office helped to initiate a lecture series for women in science and engineering, where women faculty or women in industry would come and give a short presentation about their research and there would be a reception afterward. I was the coordinator for that. The series was a good way to connect with people who had gone on to successful careers in science and engineering. It was also a way to meet women graduate students from other departments.

It sounds like you adjusted very well to Stanford. You found a good place for yourself.

I think it worked out well, especially when I found probability. For every graduate student there is this time when you are looking for an advisor: Who can I work with?

A period of uncertainty.

Yes. Kai Lai Chung was my advisor in math, but I got my thesis problem through taking courses in other departments — actually a course in the business school taught by Mike Harrison.1 So I really had two advisors, Mike Harrison and Kai Lai Chung. Stanford was a good place to do that because they had a scheme where you could have advisors from different departments. At some point [S.R.S.] Varadhan visited Stanford, and I met with him. He gave me helpful input on the problem I was working on and introduced me to submartingale problems as a way to characterize diffusion processes.

What are your memories of Kai Lai Chung?

He was enthusiastic about mathematics but also had a meticulous and elegant style. I liked that. It suited me well. Chung and I wrote a book together on stochastic integration, which grew out of a topics course he taught while I was a PhD student.2

In another advanced topics course I took with Chung, he mentioned an open problem about the finiteness of the Feynman–Kac gauge related to solutions of the reduced Schrödinger equation. A little bit later I was in a PDE course, and I realized that some technique from the PDE course could be used to look at the problem — it was actually a conjecture. Part of the problem was that it wasn’t clear whether the conjecture was true or not. I could use the PDE result to show that, at least under some smoothness conditions, the answer was yes, the conjecture was correct. That led to the first paper I wrote as a PhD student, before I was actually working on my thesis problem proper, which was on a different topic.

When you make connections like that, you know you are really a mathematician.

Yes. There’s a real thrill in discovering something new and proving that it’s correct. It’s a bit hard to describe. You work on a problem really hard, and you try this way and that way, and it doesn’t work out. But then eventually you get some idea, and it just clicks. It’s really a wonderful feeling.

Of course the first thing you do is you check it many times to make sure you’re not fooling yourself!

Feynman said that the easiest person to fool is yourself.

Yes, I think you have to be your own worst critic. That’s a useful talent to acquire, to be able to find your own mistakes.

Probability: “It was what I was looking for.”

So you met Mike Harrison through a course in the business school?

Yes. He offered a course on stochastic calculus and its applications. It was a great course, and eventually he made a book out of it, which was very well received. It was pretty standard at Stanford that graduate students from other departments would take probability courses in the math department, and also probability students would take probability-related courses in other departments.

During the course Mike would sometimes put some problems on the blackboard that were almost research problems, or little pieces of something related to research problems. So I got a taste of the kind of things he was interested in. It was a blend of applications and rigorous mathematics. After that course, I talked to him about whether there might be some research questions there that I could work on. He suggested something, and I went away and thought about it, came back, made a little progress on it — that’s how it evolved to me working on that problem with him as a coadvisor, and Kai Lai Chung as my advisor in math. So it all worked out in the end. I just followed the math to where I thought the interesting problems were.

That’s part of being a mathematician too, knowing what you find interesting and trusting that. Also having a taste for problems.

I think some of that you get with experience too. Maybe I was lucky that I already had some research experience, so I was on the lookout for problems. I didn’t really know probability at the graduate level before I went to Stanford, so that was something new for me. The first year I was taking beginning courses, and the second year I took a probability course and then started taking more advanced courses. So it took a little while to find probability, but it was what I was looking for. I really like it as a field because it touches other areas of mathematics, both pure and applied, but also it interfaces with a lot of applications. It’s the theoretical basis for statistics, it intersects with operations research and with applications in lots of different fields in science and engineering. Recently I’ve been working with biologists. Probability is a perfect field for me.

There are different parts to probability. I tend to work more on the continuous side of probability. There is also the discrete side, which tends to be more combinatorial and algebraic. I am more on the side that is closer to analysis. There are a lot of connections with analysis, but it’s built on top of analysis. If you just know analysis, it doesn’t mean you can do probability. There’s extra structure there, different problems. And there is randomness everywhere in the world, so there are lots of different things to work on.

Do you remember the so-called Monty Hall Problem that was all over the news years ago? It came from a game show where contestants had to choose which door to open, and one door would have a nice prize and the other doors would have a gag prize like a goat. A newspaper columnist wrote about the correct strategy to use in some particular case, and many mathematicians wrote letters complaining that she’d gotten it wrong. In fact the columnist was right. Do you remember this?

I seem to recall that the problem depends on exactly what you know at what point, but also on how you phrase the question.

Yes. The mathematicians who wrote letters didn’t understand the probability aspect of the problem. They didn’t have the intuition of probabilists, which is a different kind of intuition, is that right?

I agree that probability has different or additional intuition. I think of it as an extra layer that you are putting on everything else that you know. It doesn’t mean that you can’t use all of the knowledge you have from mathematics, but there is an extra layer that randomness brings.

Can you talk about that layer? What kind of intuition do you need to understand random things?

Often as human beings we are conditioned to think deterministically; we want to think deterministically. Sometimes people’s intuition leads to certain assumptions, for example, that things are equally likely when they are not, or that they are independent when they are not. I’ve seen this with dynamical systems, for example. People are very used to asking, What is the long-term behavior of this dynamical system? If that system has noise in it, you have to phrase such questions differently. A diffusion process, for example — which is a solution of a stochastic differential equation — could basically go everywhere. People are used in dynamical systems to asking: Does it converge to zero? You have to phrase the probability questions differently, like: How long does it take to get to a neighborhood of the origin? And eventually when it gets there, it might still visit everywhere else. If you have intuition that is related to deterministic motion, you don’t naturally think of those kinds of things.

So probability is great — it’s like an extra aspect that can be there, and it provides additional tools for trying to solve things.

You mentioned the course with Mike Harrison on stochastic calculus and applications. Can you give an example of an application there?

He was very interested in queueing and inventory control. It comes up in applications in manufacturing, but also the same kinds of models come up in telecommunications and even in transportation. These were queueing network models. That was my first introduction to the connection between queueing networks and diffusion processes called reflecting Brownian motions. That was a nice connection to learn about.

Stochastic calculus has as many applications as regular calculus has! And probably more. Whenever you have dynamical systems subject to noise, stochastic calculus is a tool for trying to analyze those systems. It comes up in physics, engineering, economics, and finance. The Black–Scholes equation in finance is an example of a stochastic differential equation, but you can have much more complicated finance models than that. Stochastic calculus was invented by Kiyoshi Itô and is sometimes called Itô calculus. After Itô, there was a lot of development of general theory, especially by the French school of probability.

After you got your PhD you went to the Courant Institute and worked with Varadhan.

I had already had some interaction with him about my thesis, as I mentioned. Some years before that, he had had a sabbatical at Stanford and had talked to Mike Harrison about the reflecting Brownian motion problems. Then when I was a PhD student at Stanford, Varadhan visited Stanford for a day or so, and I met him through Mike Harrison. Varadhan and I discussed the reflecting Brownian motion problem I was working on, and eventually that led to a joint paper.3 When I was at Courant, I talked to him about various reflecting Brownian motion problems.

Courant was a great place to be. On the top floor of the building they had a tearoom where people would go for afternoon tea and lunch. The faculty and students would gather there and talk mathematics. There was a very friendly atmosphere for postdocs and students. It was pretty easy to talk to the faculty. You’d sit down at lunch with Cathleen Morawetz and others.

How was it for you to meet Cathleen Morawetz?

I knew of her, but at Courant was the first time I met her. Of course she was to me a giant in mathematics, though we are in different fields. I think the first time I sat in the tearoom for lunch, she was talking about the research monograph she’d been working on over the summer. It was great to be able to meet her in this informal atmosphere.

After I left Courant, I interacted a bit with Cathleen when she was involved with the AMS [American Mathematical Society], including when she was AMS president. She was a very impressive person and always very nice to me.

There had been no women on the math faculty at Stanford, right?

There was Mary Sunseri, but she only taught calculus. I don’t think she did research. The whole time I was at Stanford there were no women researchers on the faculty.

Was Cathleen Morawetz the first woman math researcher you met?

No. I went to a few conferences when I was a graduate student in my last year and met some women researchers there. I met Catherine Doléans-Dade at one of the conferences in the Midwest. She was at the University of Illinois, a very good probabilist. I also met Cindy Greenwood, who was at the University of British Columbia, and I met a few other women probabilists when I was on the job market and visited some places.

No academic jobs in Australia

Since our last conversation, I googled “history of computing in education in Australia” and pretty quickly found your father. Westy Williams was his name?

Yes.

He was a visionary, as you said, and he had a big effect.

There’s been a little bit of history written in Bendigo about what he did, including a book published recently about the history of the college he was at. There was a nice blurb in that book about what he did there, and they interviewed me for that. The college — it’s now called La Trobe University — named the computer center after my father.

One article I found on the web noted how hard it was at the time to move computers around, because they were huge and heavy. They took up a whole room. You said the computers your father got were bought from the UK?

He was influential in acquiring several computers over several years. The first few computers I think were from England, from ICL [International Computers Limited]. Later some were from CDC [Control Data Corporation] in the US. Certainly there was nothing being manufactured in Australia; they had to come from overseas. The machine I used was huge and needed special air conditioning, which at that time was kind of a rarity. You had to try to keep the room dust-free, so initially anybody who went in the computer room had to wear little booties. But it was transformative to have access to computing power like that.

When we talked last time we left off when you were at Courant. Then you went to UCSD and have stayed in San Diego your whole career. So that was a good fit for you. When did you go to San Diego? Was that 1986?

No, 1984 was when I physically arrived. The final year of my PhD, I was looking for jobs. I got the tenure-track offer from San Diego and the postdoc offer from Courant. San Diego let me accept its offer and take leave for the first year, to do the postdoc at Courant. After that I went to San Diego. I’ve been very happy here, it’s been great. I was attracted to UCSD’s strong probability group. Ronald Getoor and Michael Sharpe were here, real experts in stochastic processes, especially Markov processes. So that was attractive for me. Of course San Diego has a great math department too.

It was a tough time when I finished my PhD. I thought initially I would go back to Australia, but there were no academic jobs there. There were few in the US, so I was fortunate to get both a postdoc and a tenure-track position.

Yes, the 1980s was not an easy time for the mathematics job market in the US — but no academic jobs in Australia!

If I’d gone back to Australia, I could have become an actuary, which is not really what I wanted to do! Not that there’s anything wrong with being an actuary, but I did have in my mind for a long time that I would like to be a university professor. I like doing research and teaching the next generation. Fortunately it worked out, but it wasn’t always clear that it was going to work out.

Developing theory for reflecting Brownian motion

I’d like to talk now about your mathematical work. A lot of it has centered on questions coming from problems around queueing networks. Can you say what these queueing networks are and give a concrete example?

I would say that my interests broadly are in stochastic processes and their applications. Initially, I worked on reflecting Brownian motion because it was an interesting stochastic process, and there wasn’t a lot of theory developed for it. It arose as an approximation to a queueing network, but there wasn’t a lot of theory developed in general for those kinds of reflecting Brownian motions.

Typically the state space was a polyhedron and reflection at the boundary was oblique, where the direction of reflection had a discontinuity at the intersection of boundary faces. This made the problem nonstandard. In the 1980s and early 1990s, I worked a lot on developing a foundational theory for such reflecting Brownian motions, especially on existence and uniqueness and characterizing their behavior. This included work with my first PhD student, Lisa Taylor. So I didn’t work on the queueing network side initially; I worked more on the stochastic process side. Then over time, it became apparent that in making that connection between the reflecting Brownian motions and the queueing networks, there were some interesting outstanding problems.

I’ll describe what a queueing network is in a moment! But in the early 1990s, people realized that these queueing networks, when they were heterogeneous — i.e., they processed different types of jobs — they could be unstable, while the analogous homogeneous networks were stable. That was a surprise. So trying to figure out when they were stable, and when they could be approximated by reflecting Brownian motions, became an important problem. For homogeneous networks, the approximation had already been developed by Mike Harrison and Martin Reiman. But for what were called multiclass queueing networks — meaning the heterogeneous case — it hadn’t been fully developed. There were two different aspects to that. You needed a theory for the reflecting Brownian motions, but you also needed to prove limit theorems that show that you could approximate the multiclass queueing networks by one of these reflecting Brownian motions.

To come to what queueing networks are: You have entities that come into a network — they could be customers, or jobs, or packets of data, or even molecules in a biological application. These entities need processing at various nodes or stations in the network. They might need to queue up to wait for processing, and that’s where the queueing aspect comes in. They might need to visit more than one station in the network before they leave, and that routing in the network can be random. So there are different sources of randomness: The times between arrivals can be random, the times to process things can be random, and the routing in the network can be random.

Queueing networks can be used to model different applications in science and engineering — things like manufacturing processes, telecommunications, also originally telephone networks, later on the Internet and wireless networks. Customer service systems and big call centers have been a source of interest in more recent times. But you can use queueing networks to model even things like biological networks, which is something I have been very interested in recently.

Stochastic networks — or stochastic processing networks — are a more general version of queueing networks. A lot of the theory of queueing networks started to be developed in the 1950s — well, it goes back even earlier than that, but there were a lot of developments in the 1950s and 1960s, though largely for homogeneous networks. A lot of the work was on exact analysis of the networks. Then in the 1960s, approximations started to be developed, both by the Russian school, especially Alexandr Borovkov, and also by [Donald] Iglehart and [Ward] Whitt in the US.4

You mentioned exact analysis, and I wonder why that doesn’t always work. Entities come into the network, they get processed, they move on — it’s a step-by-step system, so if you think naively, it seems you could create a map of everything that could happen. But it’s not that simple?

There are two things that make it more complicated. One is that there is a lot of randomness in various aspects of the model, like times between arrivals and processing times. These are usually random variables; they are not usually deterministic. The other thing is that the routing in the network could also be probabilistic, rather than deterministic, and there can be complex feedback patterns in the routing.

You might think, well, we know the average rate at which things are arriving, the average rate at which things are processed, and so forth. So we should be able to figure out under what conditions we can make it so that everything just flows smoothly through the system. If everything were deterministic, you could do that. But because of the randomness in things like the processing times, you will often get queueing. For example, there will often be instances when the amount of time it takes to process something is greater than the interval until the next arrival, so the next arrival is going to have to wait for service.

This is an under-appreciated aspect of processing networks, that randomness can cause queueing. People like to think deterministically, but the randomness in the system is important, especially if you try to balance the system, which is a natural thing to try to do. Managers of systems try to make sure that they don’t under-utilize resources, so they typically try to keep these systems in what’s called “heavy traffic”, that is, where there is full utilization of the resources. But then you can get substantial queueing and bottlenecks in the network. Randomness in anything — interarrival times, service times, and so on — affects queueing. So people try to design systems to use the resources optimally and also to understand what is causing congestion and how it might be alleviated.

That’s where mathematical models can help a lot, because these systems can be quite complex, and they can have feedback. An entity might go around several times to the same station, perhaps because something has to repeat processing or because it’s a machine that puts down many layers of a material, such as in semiconductor wafer fabrication. Once there is feedback in the system, it can be difficult to tell under what conditions the system will be stable, in the sense that the average queue lengths don’t grow without bound. In queueing there are two aspects. One is to understand how a system behaves and to study its performance, to measure things like queue lengths or idle time in the system. Another is to figure out what good controls are for the system. One of the things that I’ve worked on is Internet congestion control — for example, what kinds of policies make the system behave well. It can be very complex and difficult to understand what’s causing congestion and instability.

I mentioned the examples that came out in the early 1990s, where queueing networks that people thought should be stable under standard conditions turned out to not be stable, in the sense that average queue lengths could grow without bound. Even quite simple systems, once they have this feedback phenomenon and certain kinds of disciplines for serving or processing entities in the system, can become unstable. We understand that better now, because people have worked on it since the early 1990s.

You might ask, Why wasn’t that understood earlier? These systems have been used in manufacturing and telecommunications for a long time. Part of the reason is that, for example, in manufacturing, there were managers running around trying to resolve congestion when they found it. That’s a kind of control feature that can mask an underlying source of instability in the system, when there might have been more systematic ways to deal with it. That’s an example where mathematical models really helped people to understand these multiclass, or heterogeneous, queueing networks.

You started working on reflecting Brownian motions in the context of queueing networks. Brownian motion comes from statistical mechanics, which makes me think of atoms colliding with each other. It seems counterintuitive that something like that would apply to queueing networks.

One of the nice things about working on a theory for a mathematical object is that you might be motivated to study it for one application, but then it turns out to have other applications. Reflecting Brownian motions arise in physics and also in finance. But let me explain why it’s natural for them to come up in queueing systems.

It’s true that Brownian motion is a model for molecules colliding with one another. But also, in statistics, you can get Brownian motion as a scaling limit of a random walk. A random walk is a stochastic process that takes discrete steps, where those steps are given by a sequence of independent, identically distributed random variables. A simple example of a random walk is, you are walking on a line, and every time you take a step you flip a coin. If it comes up heads, you take one step forward, if it comes up tails, you take one step back. If you speed up time, like you’re watching a movie, and shrink the size of the steps in the right way, in the limit of the random walk you get Brownian motion.

Sums of independent, identically distributed random variables like that come up everywhere in statistics. A wonderful aspect of Brownian motion is given by Donsker’s theorem, which says that in the approximation of a random walk, all the random steps need to have is finite mean and variance, and then the statistics of the Brownian motion that you get in the limit depend only on those two statistics. It’s insensitive to the rest of the distribution of those steps. That’s called an invariance principle, in the sense that you can approximate quite general random walks with general distributions for the step sizes, by this universal object, the Brownian motion.

There are other examples of that kind of thing in statistical physics, things like KPZ [the Kardar–Parisi–Zhang stochastic partial differential equation], where you get an invariant object approximating a lot of interacting particle systems. That’s very useful. I’m building to the connection with queueing networks!

Let me just talk about a single queue. In a single queue, suppose you have a Poisson arrival process and a sequence of independent, identically distributed exponential processing times, where the average arrival rate is equal to the average processing rate. Then the queue is in heavy traffic. When the queueing system has jobs in the queue and there is a new arrival, that’s like taking a step up; the queue length goes up by one. If a job finishes being processed, the queue length goes down by one. When the queue is nonempty, it is following a (continuous time) random walk, going up by one and down by one. You can approximate that by a Brownian motion. This approximation can be generalized to where the interarrival and processing times are not just exponentially distributed, via an invariance principle. Now, when you get to the boundary — that is, when the queue length reaches zero — you need to keep the queue length nonnegative. That’s where the reflection comes in, in reflecting Brownian motion. It’s not really a mirror reflection; another term people have used is regulated Brownian motion. It’s a kind of control, or regulation, at the boundary, which keeps the process nonnegative.

In the one-dimensional case, it’s very easy to describe how to keep the queue length nonnegative. But once you go to multiple dimensions, the constraint at the boundary means that you might have one queue that becomes empty, but it’s feeding into another queue, and then there is lost potential flow to the next queue. In terms of the effect at the boundary, you get an oblique direction of reflection on the boundary rather than normal reflection, because of the structure of the queueing network. So these reflecting Brownian motions have what’s called oblique reflection at the boundary of, say, an orthant in \( d \)-dimensional space, where \( d \) is the number of stations or nodes in the network. They are different from many of the reflected diffusions that were studied earlier, which were often in smooth domains with normal reflection.

When I started to get involved in this area, there was a little bit of theory for these obliquely reflected Brownian motions associated with approximations to homogeneous queueing networks. However, there wasn’t a theory to cover other approximations, in particular, those coming from most heterogeneous queueing networks. So one of the things I was involved in early on was developing a theory for these reflecting Brownian motions that would cover more of a full spectrum of the stochastic processes you would expect to get. I always had in mind the queueing applications, but I didn’t really start to work on proving queueing limit theorems until a bit later on, after I had developed theory for the reflecting Brownian motions. It was in the 1990s that I started working on proving limit theorems. Before that, I was working a lot on the fundamental theory for the reflecting Brownian motions.

Regarding limit theorems, in the late 1990s, Maury Bramson and I coordinated in developing a modular approach5 to proving heavy traffic limit theorems for multiclass queueing networks. This involved using the asymptotic behavior of hydrodynamic limits, called fluid models, to prove a dimension reduction on diffusion time scale, called state space collapse, which then fed into proving a diffusion approximation for the queueing network.

Broadening research through collaboration

You’ve had many collaborators over the years. Can you tell me about what collaboration means to you?

I have been fortunate to have many wonderful collaborators. These range from PhD students and postdocs to colleagues at UCSD and around the world. These collaborators have included mathematicians, as well as researchers from fields of application such as biology, cognitive science, control theory, and operations management. While some collaborations have been with students, postdocs, visitors and colleagues at UCSD, a substantial number have come from extended visits I have made to programs at research institutes, and also on sabbatical visits to various universities around the world. I found such visits especially useful for learning of new research problems and making connections with new collaborators to work with. Support I received from UCSD, as well as from various fellowships and institutions, was invaluable in making such visits possible. This was especially important early in my career and has continued to be an important way for me to broaden my research.

One of my collaborators is my husband of 30 years, Bill Helton, who is also a mathematician at UCSD. Bill has a great sense of humor and has been very supportive of me in my career. Although he is in a different field, we wrote a couple of papers together. One of them, with Gheorghe Craciun, was on homotopy methods for counting reaction network equilibria and grew out of an IMA [Institute for Mathematics and Its Applications] workshop.6 The other paper I have with Bill was written with two other collaborators, Frank Kelly and Ilze Ziedins, both experts on stochastic networks. That paper was on analysis of a traffic network with information feedback and onramp controls.7

You mentioned the biological applications you have been working on recently. Can you tell me about that?

Since the 1990s, I worked on queueing in more general stochastic networks and proving limit theorems that justify various continuous stochastic processes as approximations, including certain measure-valued (infinite dimensional) processes. I also got interested in control problems for these stochastic networks. In the mid-2000s, inspired by another workshop at the IMA, I became interested in models that came out of biological networks. I thought that was a very interesting direction for applied probability. I started investigating what are called stochastic chemical reaction networks. And one of the things I realized pretty quickly was that to work on applications related to biology, it was good to be connected to people who did experiments, as Sam Karlin had told me.

I found there was a group here at UCSD working in synthetic biology, led by Jeff Hasty and Lev Tsimring. They were using some stochastic and deterministic models to approximate small genetic circuits. That seemed very suitable as a potential ground for stochastic modeling and analysis. At that time NSF [National Science Foundation] had a nice program called Interdisciplinary Grants in the Mathematical Sciences, which aimed to encourage mathematicians to spend a year visiting a group in another discipline in which they had never worked before. This was ideal for me, because I hadn’t collaborated with biologists before. I applied for one of those grants and got it, and I went to visit the Hasty–Tsimring lab for a year.

We ended up working on some stochastic models of enzymatic processing, which you can think of as queueing-like models. As usually happens, initially you can use some existing theory, but then you have to extend it in different ways to adapt to the different situations. That was a great collaboration that went on for several years with the lab and got me my start in collaborating with biologists, especially with people who were doing cellular and molecular biology.

The visit I made to the Hasty–Tsimring lab was partly a sabbatical that I had from UCSD. In 2019 I had another sabbatical, this time in Boston, visiting the Center of Mathematical Sciences and Applications at Harvard, and also MIT. While there I connected with Domitilla Del Vecchio, who is also a researcher in synthetic biology. We have an ongoing collaboration about modeling epigenetic cell memory. I find it very intriguing to work on stochastic network models like this, where there is a need to develop some new theory. Also, often I find if you work on an application, questions come up that haven’t already been answered by the existing theory. It’s a good way to get natural questions and make sure you are asking good, challenging questions. I find this collaboration very exciting.

That’s amazing you jumped into this new area. Was it difficult to get up to speed to be able to talk to these people who were doing such a different kind of work?

I had collaborated before with engineers, in mechanical, industrial, and electrical engineering. But I found that collaborating with biologists, I had to stretch further. Biophysicists were good intermediaries. They often use mathematical language but also know the experimental side. Lev Tsimring is a biophysicist, and Jeff Hasty trained as a biophysicist, although he is very involved in experiments now as well. There was also a talented biophysics postdoc, Will Mather, whom I talked with a lot when I went to the Hasty–Tsimring lab. That helped a great deal. Generally in interdisciplinary collaborations, it’s a real team effort.

But I found initially that reading biology papers was like learning a different language. In a mathematics paper, often there is a succinct formula, and if you understand the formula, you understand a lot about what is going on. The biological papers used a lot more words and fewer formulas. When I gave talks, I found that even though there might be a beautiful formula that you could show, it was important to do things like show a graph of an instance of the formula — even though one formula is worth a thousand graphs! It’s just a different way of presenting things. I definitely felt that there was a steep learning curve in starting to collaborate with biologists, but I had very good people I could talk to. Often it’s the postdocs and the graduate students who you can talk to on a daily basis and learn many things from.

In engineering often there is already a model, but in biology often there’s not. You can make a model that’s so complicated that you wouldn’t be able to do anything with it. So you have to ask a lot of questions about what’s important to put into the model. Also, there are often parameters that aren’t known very precisely. For all of that it was very helpful to be embedded in the lab.

After you developed these biological models, how were they then used?

In the Hasty–Tsimring lab, and also in the work that I’m doing now with Domitilla Del Vecchio at MIT, the models help to guide the experiments. As is typical in applied math, there is a feedback loop: You do an experiment, and you find that maybe the results are a bit different from what the model is predicting, so you go back and refine the model. The model is also very helpful in exploring different parameter regimes that you might not be able to fully explore with experiments, which can be very costly. Some of the models I’ve worked on might be eventually used to help combat disease, although what I am doing at the moment is more basic science.

An “Aha!” moment earns an ice cream cake

What do you do when you do mathematics? Do you go out for a walk and look at the trees? Do you lie on your back, close your eyes, and enter some other world? How does it work?

I mostly sit with a pad and paper, but I always find it’s helpful to take a walk and think. I have to admit that math is in my head a lot of the time! It’s kind of a natural thing. When you are working on a problem, you first have to learn enough about it so that you can carry it around in your head and think about it. But it doesn’t take a holiday — it’s always in your head!

The probabilist

Chris Burdzy

had a Warschawski Visiting Assistant

Professor position at UCSD some years ago. We had a probability

seminar where Chris was giving a talk one day. He mentioned an open

problem and said that, if somebody solved it, that person would get

an ice cream cake. Well, I was interested in the problem, not

necessarily the ice cream cake! But later that week I was taking a

walk across a park in San Diego, and I had an idea about how to

solve this open problem. That was an “Aha!” moment. It turned out

it was a good idea, and Chris and I wrote a paper

together.8

At the

departure party for Chris when he went on to his next position, the

ice cream cake appeared.

He made good on his promise.

He did, yes. Math is in my head a lot of the time. That’s just the way it is. It’s a passion.

You said you have to know enough about the problem to be able to carry it around in your mind. Can you talk about what that thing is that you carry in your mind? Is it a picture? Equations? Shapes? Or some process that unfolds? What does that look like?

I’m a visual thinker. A lot of the problems I work on involve stochastic processes, and I am often interested in what people would call the sample path behavior. For example, consider reflecting Brownian motion in three dimensions, which lives in the positive orthant, or in two dimensions, which lives in the positive quadrant. It runs around like Brownian motion, but it’s got this reflection at the boundary. So I have those pictures in my mind, of how the sample paths behave. Often you are interested in questions like, does a sample path hit the corner of the quadrant? How long does it take to get there? Then sometimes equations or constructs come to mind about how you might prove that.

I don’t really see line-by-line proofs when I visualize things, it’s more trying to get an idea about how to solve the problem. I’m a geometric thinker. Even with stochastic processes, I think about the geometry of what’s going on, especially how these sample paths behave, which has connections with analysis.

A sample path for reflecting Brownian motion is basically a continuous path, so you are following this random continuous function as it moves around in a state space. The boundary behavior is a bit singular, so things are not usually absolutely continuous, and that’s a little bit tricky, but it’s a kind of stochastic differential equation with state constraints. To connect with analysis, a useful tool is stochastic calculus, or Itô calculus, which I mentioned before. When I think about how to apply those tools, usually then I would want to get my pencil and paper out and start writing things down, because it’s easy to fool yourself at that stage!

Do you do any programming now, say to carry out little experiments that might occur to you?

I often have some graduate students, or occasionally a postdoc, do some programming, especially in Mathematica. So for example with the biology models at the moment I have a very good graduate student helping me with that, Yi Fu. A wonderful thing that’s changed since I first wrote computer programs is that there are a lot more high-level languages now, things like Mathematica and Matlab. So sometimes I’ll write a little Mathematica code, maybe to illustrate a theorem or test a conjecture. If students write the code, sometimes I’ll tinker with it and produce examples and test different scenarios.

Also, I coteach a computational finance course in the Rady School of Management, where we teach some algorithms, though for most of the coding, we have a TA who helps.

Have you also done research in finance, or this is just a course that you enjoy teaching?

I’ve always had a little bit of an interest in finance, because it’s an application of stochastic calculus. So I developed a course at UCSD on mathematical finance and wrote an introductory book, which is published by the AMS.9 At UCSD we have both an undergraduate- and a graduate-level mathematics course based on that book. In addition, I am coteaching the computational finance course with another mathematics professor. Finance is a good application of probability, and also students often want to get some background in it, to enhance their job opportunities. We have students from other departments who take our mathematical finance courses too, especially students from economics, also sometimes from physics and engineering. It’s a popular topic.

It sounds like you have a lot of diversity in your work.

Yes, I feel that, and I also feel that what I have worked on has changed with time. I’m always looking to find new opportunities. I like working with other people, and I like working on problems and developing new mathematics. I have an open mind to that. I am better at certain kinds of mathematics than others, so I tend more to the analysis side.

Encouraging the next generation

You said that in Australia you had to learn how to follow lectures and listen to people. Do you see students today developing that skill? Everyone is watching video lectures and reading material on the Internet.

I think there is a lot of concern about that. I’m by no means an expert, but the ability to focus and listen to somebody when they are speaking or giving a lecture, and taking notes as well, are important skills that not everybody has these days. I think there is a tendency with videos for people to just skip through them and not really absorb a lot. That actually can make it more difficult to learn the mathematics.

There is something about writing on a blackboard, and the pace that comes with it, that seems to be very helpful for people to be able to absorb things. Mathematics itself is a kind of shorthand language, and in a lecture you are trying to absorb that language as well as new concepts. If you just fly through it in a video, you might not absorb it very well. And we’ve seen that if students have videos to watch, they don’t necessarily do as well as if they come to in-person lectures. I’ve seen that in my own classes, and also other people have reported it. It’s a challenging issue. Learning new mathematics takes time and patience and practice.

When we talked about your early life in Australia, you said you didn’t encounter the attitude that “females can’t do mathematics.” In fact, you were very much encouraged by your parents and teachers. How was it later in your career? Did you feel that being a woman in mathematics was an issue, or caused any problems, or set up any obstacles?

One thing I noticed is that the further you go up, the fewer women there are. I’ve tried to encourage people who were more junior than myself. I find that I’m most helpful at the individual level. I think the most valuable thing is if you can provide help and advice that is adapted to the individual, whether a man or a woman — things like reviewing a person’s grant proposal or commenting on a draft of their research statement. That all takes time, but those are the kinds of valuable things that really help.

A different way of helping is through professional service, and I have done a lot of that with various organizations.10 I find it is one way for me to give back to the organizations that have benefited me in my career and that foster mathematics and science research. Their role in helping junior researchers is especially important.

Going back to the issue of being a woman in mathematics — it’s sometimes said that women have less confidence than men, that women lack confidence. As you spoke about your life, that didn’t seem to come up. You just were interested in math and science, and then the question of confidence, the question of “Can I do this?”, got subsumed by the desire to learn and understand. To assume that you have to be extremely confident that everything will work out is maybe not necessary or realistic.

When you are working on a mathematics problem, you don’t know whether it’s going to work out! I feel that I just have to try and follow what I think is interesting. But everybody worries, “Will I be able to solve this problem? Will I get my PhD? Will I get tenure?” I think that’s natural. In working on mathematics, there’ll be times when it’s tough, when a problem doesn’t seem like it’s yielding, and you just have to try and push through, or step back and take an alternative approach. Maybe with experience one gains that perspective, which is a bit harder to have in the beginning. But I don’t think being overconfident is good!

You said about a professor you had in Australia, “I liked his mathematical style.” Even at that early stage you were looking out for what was interesting to you, what you were drawn to, what appealed to you, instead of worrying, “Can I do it?”

That was definitely true in my undergraduate studies. When I did my PhD, it took me a little while to find probability as the right field. I just tried different things and kept looking. It was persistence, or stoicism — Australians tend to be stoic! Working hard helps. And definitely there were people who helped me along the way, and I am very grateful to them. I’ve been very lucky.