by Allyn Jackson

“Your living room is your factory.” That’s a slogan that Sun-Yung Alice Chang (張聖容) heard often among families like hers when she was growing up in post-World War II Taiwan. “Everybody did some handiwork in the living room, making Christmas decorations” and other trinkets for export, she recalled. “Every family did that to have some extra income.” Her parents came from wealthy families in China, but once they were in Taiwan, said Alice, “they had to start from ground zero.” Her father, who had trained in China as an architect, worked in building construction. He did not earn enough to support a family with a daughter and son, so Alice’s mother became an accountant, learning the trade on the job. Most of their combined income went toward food. Subsidized housing allowed the family to survive. When Alice was a student at National Taiwan University (NTU), she received a prize consisting of a set of textbooks for the next academic year. “My family celebrated that,” Alice recalled. “It was a relief.” Textbooks were a big strain on the family budget.

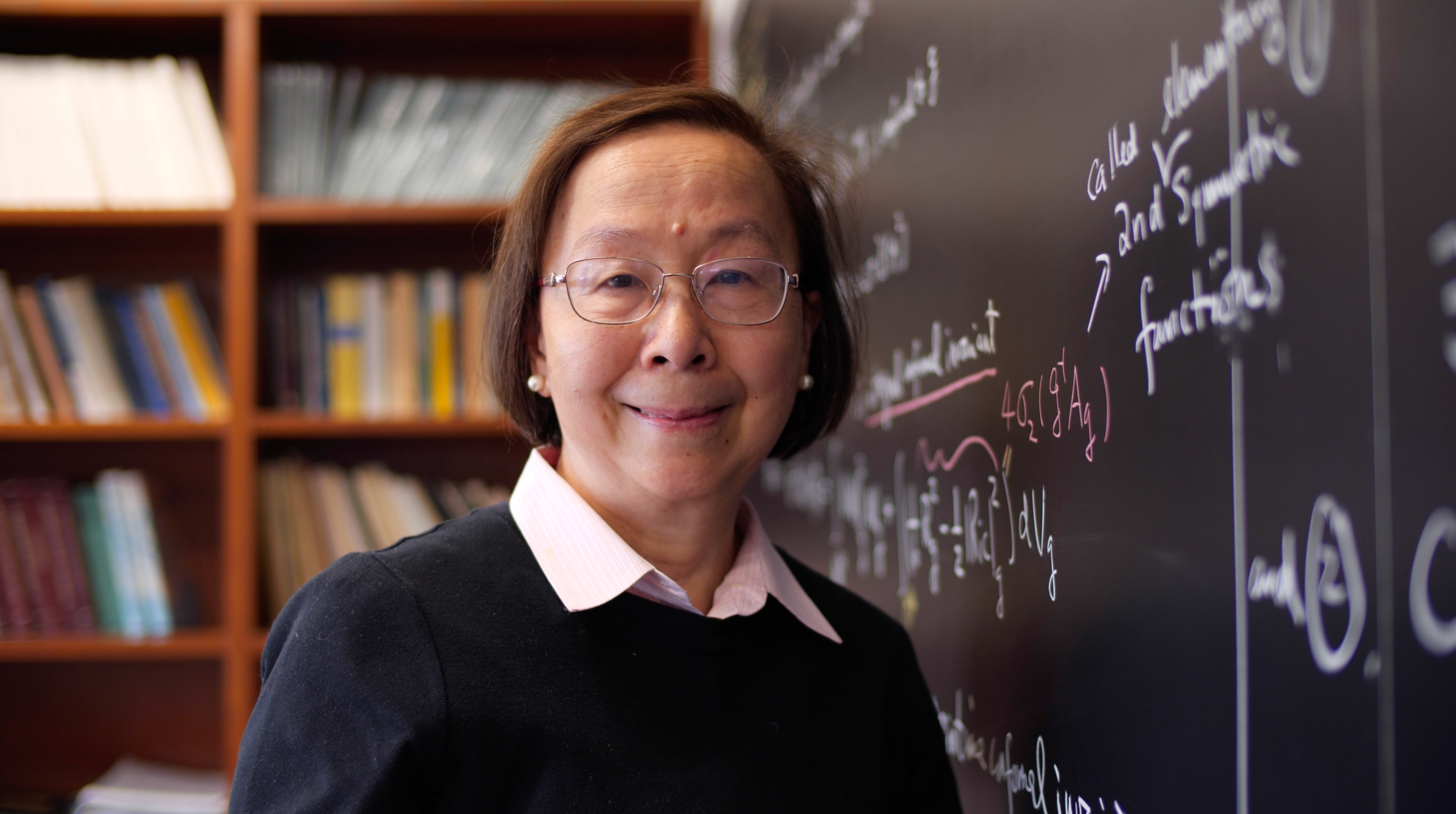

(photo credit: Nick Donnoli).

Alice, who today is Eugene Higgins Professor of Mathematics at Princeton University, is one of six women who received bachelor’s degrees in mathematics from NTU around 1970, went on to PhDs in the United States, and rose to the top of their profession. The great geometer Shiing-Shen Chern (陳省身) once marveled at the accomplishments of these six women, calling this burst of female mathematical talent in Taiwan a “miracle”.

This “miracle group,” as I will call them, lived through an inflection point in Asian history. Born around 1950, they grew up in a Taiwan bearing little resemblance to the high-tech powerhouse the island has become. Taiwan was an impoverished land under martial law, struggling to emerge from the shadow of geopolitical conflicts that had shaped its fate for half a century.

Despite economic hardship and the strictures of a conservative, patriarchal society, the miracle group pursued an idealistic dream of intellectual achievement in a male-dominated field. They had few role models; their career paths were uncertain. But they knew they loved mathematics. And they had each other, as classmates at NTU, as loyal friends, as sources of inspiration.

“It was a good thing to have so many girls” studying mathematics at NTU, said another miracle group member, Jang-Mei Wu (吳徵眉). “Everybody talked about it being hard, but everybody made an effort… Seeing this group of women classmates, I kept on going. We all just kept on going.”

History of an island shaped by outside forces

Today Jang-Mei is a professor emerita of mathematics at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. Like the other women in the miracle group, she grew up at a time when Asia had barely begun to heal from the fractures of World War II. Her father, who had studied civil engineering at Fudan University, worked in railway administration in Hangzhou, China. In 1948, the year Jang-Mei was born, he was sent to Taiwan to help rebuild railways damaged by wartime bombing raids. His wife joined him in Taipei the following year and soon had a second daughter. Economic conditions on the island were harsh; even professionals like Jang-Mei’s father could earn only enough to cover basic needs. In those days her mother spent all her time on housework, doing everything by hand: sewing, knitting, washing clothes, bringing ice from the market to keep food cold, cooking over a charcoal fire that had to be tended morning to night. “It was really hard work,” said Jang-Mei.

The parents of Alice and Jang-Mei, and those of the other four women in the miracle group, were among the two million people who left mainland China for Taiwan around 1949 and entered the flow of history of an island that had been molded and exploited by a succession of outside forces.

For thousands of years aboriginal people lived on Taiwan and developed their own culture, with little influence from China. It was the Dutch colonists, arriving in the 17th century, who encouraged Chinese people to come to Taiwan, as manpower for farming and for exploitation of the island’s resources. But Dutch control of the island was brief: after a mere four decades, the colonists were forced out and Taiwan was gradually integrated as a province of China. Two centuries later, the Chinese themselves were compelled to relinquish control of the island, when Taiwan was ceded to Japan at the end of the first Sino-Japanese War in 1895.

Again Taiwan came under foreign rule, as the Japanese imposed their own national identity and culture on the island. The Japanese brought many improvements, including electricity, modern medicine, and infrastructure such as railways. But they also exploited the island and treated the native Taiwanese as second-class citizens, compelling them to adopt the Japanese language and limiting their educational and professional opportunities. The Taiwanese who objected to the systemic discrimination were dealt with harshly or even killed.

In 1945, after its surrender in World War II, Japan ceded Taiwan back to China, and the island was once again compelled to take on a new identity. The Kuomintang (KMT) Nationalist Chinese forces then in power in China undertook a process of “de-Nipponization” of Taiwan, to root out Japanese influence and to establish the Mandarin language and traditional Chinese culture as the foundations of society. Initially these changes were welcomed on Taiwan. However, the KMT soon became suspicious of the islanders, seeing them as collaborators of the enemy Japanese; the islanders in turn became resentful of the heavy-handed and sometimes brutal tactics of the new regime. To assert its authority in the increasingly tense situation, the KMT in 1947 established martial law, which remained in place for more than forty years.

In 1949, the KMT Nationalists, under Chiang Kai-Shek, lost the Chinese civil war to Mao Tse-Tung’s Communists and retreated to Taiwan. Along with Chiang’s military forces came a wave of civilian refugees, including bureaucrats and technocrats in the Nationalist government as well as university students, scholars, and intellectuals. Taiwan’s existing population of six million absorbed two million mainland Chinese.

That year Jang-Mei Wu’s mother left behind her large family in Hangzhou, including several sisters to whom she was very close, and set out by boat for Taiwan, where her husband awaited her. She carried the baby Jang-Mei with her on the multiweek trip. “When [my mother] talked about the time on the boat, she said she was happy…because she had a baby, and she was going to her husband’s place,” Jang-Mei said. Her mother assumed that she, together with husband and child, would soon return to China and go on living there. Said Jang-Mei, “She never, never thought that she would be in Taiwan for all her life.” None of the migrants did.

Living as refugees, escaping upheaval

Born in Hua-Lian, a port city on the east coast of Taiwan, in that tumultuous year of 1949 is another miracle group member, Chuu-Lian Terng (滕楚蓮), who today is a professor emerita of mathematics at the University of California, Irvine. Chuu-Lian grew up in Taipei, in what might today be called a refugee camp, albeit one with houses not tents. Built for families of men in the Nationalist army, the houses were tiny mud-and-bamboo structures without foundation. They were designed to last only two years. “After 5 or 6 years, [the walls] started to warp and make a curve,” Chuu-Lian recalled. “You could hear the neighbors. Every time when a hurricane came, they moved us to the high school nearby.”

The short shelf-life of Chuu-Lian’s family home reflected the frame of mind of the refugees and indeed of Chiang Kai-Shek himself, who planned to retake the Chinese mainland and reestablish the Nationalist government there. Developing Taiwan became part of this plan, as Hsiao-Ting Lin explained in his book Accidental State: “Chiang stressed the necessity of cultivating Taiwan’s cultural, social, economic, and educational assets, in what would later become known as ‘soft power,’ to be used one day instead of military force to overthrow the Communist regime on the mainland.”1

The miracle group benefited from this development. They were also spared years of upheaval and violence on the mainland, as Mao Tse-Tung and his followers remade the economy and society to conform to Communist principles. Alice Chang’s parents, poor as they were, sent parcels of sugar and other staples back to their families struggling to survive on the mainland. All communication, including mail delivery, was cut off between Taiwan and mainland China, so the parcels had to be routed through family friends in Hong Kong. After US President Richard Nixon’s “reopening” of China in 1972, Alice’s parents were finally able to visit and see how their relatives had fared. “We found out they had a really difficult time,” she said. Of her father’s three siblings who stayed in China, none had been able to send their children to college. Having come from rich, land-owning families, the kids were forbidden higher education. Most of them became farmers.

A harsher fate befell the relations of another member of the miracle group, Fan-Rong King Chung (金芳 蓉), who is now a professor emerita of mathematics and computer science at the University of California, San Diego. Fan’s mother too visited China after 1972 and learned that whole branches of her family — three uncles, together with their wives and children — were gone. Asked if they had been killed, the usually voluble Fan replies only with a quiet “mm-hmm.” These relatives had belonged to the well-off class of landowners who were systematically persecuted by the Communists. “People really suffered during those times,” said Fan. “In Taiwan, we were totally shielded from all that,” she went on. “We all were told we were very lucky because in Taiwan, there was peace and prosperity.”

Taiwan schools: Heavy on discipline, but also on learning

Wen-Ching Winnie Li (李文卿), another member of the miracle group, was born in Taiwan in 1948 and is today a professor of mathematics at Pennsylvania State University. Her father was a chemist who came to Taiwan in 1946 to run a salt company that the Nationalist government had taken over; her mother came the following year. In China, salt was historically an important commodity, and being a salt merchant meant wealth. But this did not apply to Winnie’s father. Even though her parents had only one child, and even though the salt company provided free housing, the family lived paycheck to paycheck. “The money went to food and clothing, all the necessities,” said Winnie. She never lacked anything but never had any little luxuries either. “I don’t recall that I went to any movies with my parents. Never.”

Winnie grew up in Tainan, on the southwest coast of Taiwan. Her life was quite restricted, not only because her parents were protective of their only child but also because of the conservative, authoritarian society. All schoolchildren wore uniforms, with name tags for boys and identification numbers for girls. When school ended for the day, guards monitored students in the streets and on public transit to make sure boys and girls did not mingle. “The ID numbers and names were convenient for them to take notes about who was doing what and where and when,” said Winnie. The girls had only numbers, she explained, in order to better protect their privacy.

In most schools in Taiwan at the time, the early grades were coeducational, and the genders were separated starting in the seventh grade. During the Japanese colonial period, schooling for girls differed from that of boys, in keeping with the aim of making girls into “good wives, wise mothers.”2 After the KMT took over the schools, the curricula were made the same for both genders, thereby greatly improving girls’ educational opportunities.

After 1949, as mainland China began reshaping the basis of its educational system around communist and Maoist principles, Taiwan was building one that would retain and strengthen traditional Chinese values. The KMT made Mandarin the language of school instruction in Taiwan and suppressed local languages. Political inculcation included the teaching of the “Three Principles of the People” of KMT founder Sun Yat-Sen as a required school subject. Students learned about the dangers of communism and the importance of a Nationalist revanche of mainland China.

School days would begin with singing the national anthem and watching the raising of the flag of the Republic of China, symbolizing Taiwan together with the soon-to-be-conquered mainland. After that came a hygiene check. “You had to bring four items to school every day,” explained Jang-Mei Wu: a handkerchief, a drinking cup, toilet paper, and a mask. “If you didn’t have these four items, they mark you down, and the next day you must have them.” What was the mask for? At the end of the school day, the kids had to clean the classrooms — sweep floors, clean windows, wipe down desks — and were required to wear masks during these chores.

Schools maintained strict discipline, sometimes by corporal punishment, and kids were expected to work very hard. Still, the miracle group enjoyed school. Among the refugees from mainland China were many scholars and university students, some of whom became schoolteachers in Taiwan and contributed much to the academic quality of the schools. Chuu-Lian remembered getting a “wonderful classical education.” “I was lucky, all my teachers were good teachers,” she said. She remembered them as mostly young and poorly paid, but dedicated and enthusiastic.

Especially memorable was her sixth grade teacher, Xian-Geng Zhou (周賢耕) who after his day job attended university classes at night and later got a PhD in economics in Japan. One time he wrote on the board the numbers 1, 2, 3, …, 98, 99, 100, and told the kids to add them all up. “I said, ‘How can you add them all up?’,” Chuu-Lian recalled. “It would take a long time. So he waited for a few minutes, then he just drew a line from 1 to 100, 2 to 99, and so on. A few lines, then you got it. And I thought, That’s fun!”

Teachers sometimes gave problems from traditional Chinese mathematics instruction, such as: Given a cage containing rabbits and chickens, and the number of heads and of feet, calculate the number of each kind of animal. “If you don’t have algebra, it’s difficult to solve,” Chuu-Lian said. “We were trained from fifth grade on problems where you really have to think.”

Patriarchy with a lighter touch

Fan Chung’s parents married in China and went to Taiwan for their honeymoon — and then stayed. Fan was born in 1949 in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, where her father, who had trained as an engineer, worked in manufacturing for the military. His salary, together with that of Fan’s mother, who worked as a high school teacher, meant that Fan’s family was a bit better off financially than the families of the other miracle women. Fan has one brother, who got a master’s degree in civil engineering in the United States and then had a career in Taiwan.

Fan’s father encouraged her love of mathematics. “My father said, ‘Mathematics is the foundation of science. If you do math, you will be good at anything. You can always switch to other areas later if so desired.’ And he was right.” Fan learned just how right he had been when years later she began to do research at the border between mathematics and computer science. Her father also pointed to teaching as a fitting career for a woman. Here Fan did not take the hint. After her PhD she spent twenty years at Bell Laboratories, which was legendary for its thriving research-only environment.

Fan’s parents did not follow the traditionally patriarchal pattern of Chinese society and favor their son over their daughter. In fact, that kind of favoritism did not play a strong role in the families of the miracle group. It was entirely absent for Winnie Li, as she was an only child, as well as for Jang-Mei Wu, whose parents had two daughters. In the families that did have sons, the daughters were not treated very differently. Taiwan historian J. Megan Greene of the University of Kansas suggested that, because the parents of the miracle women came from educated backgrounds in China, they might already have begun to question received ideas like patriarchy even before coming to Taiwan. In addition, the lack of contact with their extended families might have attenuated the force of such traditions.3

Still, the parents of the miracle group often paid greater attention to their sons — sometimes to the advantage of the daughters. Chuu-Lian Terng’s father was “very old-fashioned, very traditional,” she said. He expected all four of his children to excel in school, but his high career expectations were trained only on his three sons and not his daughter. “He had no real career goal for me,” said Chuu-Lian. As a result, when it came to college, “I had complete freedom to choose what I wanted to do.”

In Alice Chang’s family, patriarchy did not reign, for her mother was definitely the boss. She was known in the neighborhood for being extremely strict with her kids. “My brother and I united to try to protect each other,” Alice recalled. “We were scared of her.” She required top academic achievement of both children and often kept them indoors for extra study or calligraphy practice while other kids went outside to play. “She would say, ‘My kids have to be the best’,” Alice recalled. “Nowadays in America we would say she was a ‘Tiger Mother’,” said Alice, referring to the 2011 bestselling book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother by Amy Chua.

Having had a younger brother herself and having chafed under her status as the lesser child, Alice’s mother was determined not to do the same with her own daughter. But there was a twist. “My mother tried to treat my brother and me the same,” Alice explained. “On the other hand, it was understood that I was being specially favored to be treated the same. I shouldn’t take it for granted! In other families, boys come first. I was always reminded of that.”

Scores, exams, rankings: A hierarchal system

We have so far met five of the six miracle women: Alice Chang, Jang-Mei Wu, Chuu-Lian Terng, Fan Chung, and Winnie Li. The sixth is Mei-Chi Shaw (蕭美琪), who is a few years younger than the others. Born in 1955 in Taipei, she is today a professor of mathematics at Notre Dame University. Mei-Chi’s father studied physics as a young man in China and then became a meteorologist in the Nationalist Air Force; later, after he fled with his family to Taiwan, he became editor of the Force’s magazine. He loved Chinese literature, the subject that Mei-Chi’s mother had studied at Wuhan University.

Mei-Chi grew up in a large family, with four brothers and a sister, in a ramshackle barrack much like the one where Chuu-Lian Terng lived. In an autobiographical article4 Mei-Chi related happy memories of flying kites on the rice paddies in Taipei — as well as the importance of bringing home all the threads used as kite string. “At that time, material things were so scarce, everything was precious, even a spool of thread,” she wrote.

For Mei-Chi, as well as the other miracle women, a dreaded rite of passage was the entrance examination required to progress from sixth to seventh grade. Mandatory schooling ended at sixth grade, and the only way to continue to seventh grade in a public school was to score well on the exam. Mei-Chi’s family was unable to afford private schooling, so failing the exam would have meant the end of her education. She never felt pressure over an exam like she did for this one. She wrote, “Both teachers and parents alike warned us that if we did not pass the exam to get into public school we would be sent to ‘tend buffalo’ (figuratively speaking).”

Many schools spent the entire sixth-grade academic year preparing students for the exam. Cramming sessions kept students at school until late in the evening, and families of means paid for outside tutoring. Chuu-Lian’s family could barely afford the minimal public school fees, let alone extra tutoring. She felt the pressure of the exam starting already in the fifth grade, when her father told her that if she did not pass she would have to become a maid. Before that time, “I had never worked at home in the evening,” she said. That evening, “I turned on the light and started to work.”

In Taiwan’s competitive, hierarchical education system, students were ranked numerically not only on major examinations like the one leading to seventh grade but also within their classes and within their schools. At the high school level, there was also a pecking order based on which school one was able to get into, with the First Girls’ High School being the most prestigious and the Second and Third Girls’ High School one and two notches lower, respectively. High-school-level vocational schools were yet lower on the totem pole.

After the exam to enter the seventh grade came two more exams, for ninth grade and then for college. At each level the weeding-out was considerable, but for girls, the drop-off was especially steep. For example, in the year 1969, nearly all boys and girls ages 6–11 were enrolled in school. But for ages 15–17, only 43 percent of boys were enrolled — and just 31 percent of girls.5

During the 1960s the government ran an experiment on Taiwan’s offshore islands of Quemoy and Matsu, in which the exam for seventh grade was eliminated. The result was “noticeable gains in weight, height, and general health of sixth-grade children, and also lessened incidence of eye troubles.”6 Mei-Chi Shaw was in the last cohort of students taking that exam. In 1968, Taiwan eliminated it entirely and expanded universal schooling from six to nine years.

Scholars as celebrities

Madame Wu was the nickname for the physicist Chien-Shiung Wu (吳健雄), who carried out the experiments that were the basis for the work that earned Yang and Tsung-Dao Lee (李政道) the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1957. In 1964, when Madame Wu received an award from a cultural foundation started by a cement company in Taiwan, the monthly magazine Taiwan Review carried a long article about her — making sure to mention that she was a devoted wife and mother, as well as a good cook. Mei-Chi remembered seeing newspaper articles in 1964 reporting on the first woman to earn a PhD from Princeton University, Taiwan-born Tsai-Ying Cheng (鄭彩鶯), who studied biochemistry and did cancer research before moving into plant biology.

This respect and admiration for women’s achievements coexisted with patriarchy. In traditional Chinese culture, the status of women was lower than that of men, Mei-Chi explained. “But historically there are a lot of talented Chinese women who were poets, who were painters, calligraphers, and so on,” she noted. “Talented women are very much valued and respected.” As a result, in Taiwan, even though boys were expected to achieve more than girls, those girls who aspired to academic excellence did receive encouragement. They were sustaining the cultural tradition of female talent.

The celebrity intellectuals were an inspiration for the miracle group but seem not to have functioned quite as role models, in the sense the term is commonly used today. This is illustrated in Alice Chang’s recollection of a lecture by Chen-Ning Yang that she attended in Taipei when she was in high school in the mid-1960s. In the lecture, Yang said that if he were a young person entering university at that time, he would opt for mathematics, because the field was witnessing rapid and fascinating developments in many directions.

“Yang’s comment left a deep impression on me, as I thought, ‘what a chance, or privilege, I would have to enter an exciting, developing field’,” said Alice. “Whether I could become a research mathematician, or remotely reach the heights that Professor Yang reached, actually did not seem to occur to me.” She did not quite view him as a role model, meaning someone who was like her, someone she could identify with and emulate. What hooked her was less the desire to be like him than the appealing vision of mathematics that he presented.

In a similar way, Jang-Mei Wu did not see the celebrity intellectuals as role models. “I heard of all these people when I was young,” she said. “But I chose math just because I like math. That’s it.” In high school she and a friend solved math problems together and puzzled over Sherlock Holmes mysteries (in Chinese translation). These are the kinds of experiences that sparked her interest. Her desire to do mathematics “was just from inside me. It was not because I wanted to be somebody.”

Choosing mathematics — and learning what it is

The 1950s and 1960s were a time of huge growth in higher education in Taiwan, with the number of colleges and universities increasing from 4 to 22. Enrollments increased by an even larger proportion. Nevertheless in 1970, only 8 percent of the population of 18- to 24-year-olds was enrolled in higher education.7 Attending university was a great privilege that students worked very hard to attain. This was especially true for those who hoped to enter National Taiwan University, which was (and remains today) Taiwan’s premier higher education institution.

In 1966, 43 students entered NTU as mathematics majors, twelve of them women. Of those twelve, around half had done so well in high school that they were not required to take the university entrance examination. There is a special term for this in Chinese, bao song (保送), which literally means “guaranteed send.” Bao song students could choose any university and any major. Among the bao song NTU math majors starting in 1966 were three from the miracle group: Alice Chang, Winnie Li, and Fan Chung. “Our class was special,” said Alice. “It had never happened before” that so many of the top women students chose mathematics. Chuu-Lian Terng entered NTU the following year, in 1967, also a bao song. Her class also had an unusually high proportion of women math majors, eight out of thirty.

“The general thought was that the best students should go to medical school” to ensure a secure, well-paid career, said Winnie. When she chose math, her parents made no protest but her high school teachers were disappointed. “They said, ‘This is such a splendid opportunity for you to go to medical school, and you’re just not doing it!”’ she recalled. At this time the governing KMT was strongly encouraging young people to go into science and engineering, as a way to build Taiwan’s industrial capacity. But this encouragement seems not to have exerted a big influence on the miracle group. Said Jang-Mei, “We didn’t think about practical things. We didn’t think about the future, about whether math has a future. We liked math, so we chose that.”

In some sense they didn’t know quite what they were choosing, because the mathematics they had learned in high school — the usual fare of algebra, geometry, trigonometry — was very different from what they studied in college. And what mathematics might be like further on, as a field of research, was totally opaque. “I had no idea what it meant to be a research mathematician,” said Chuu-Lian. “I didn’t even know what research is, when I was an undergraduate.”

They got an inkling in a freshman course called “Introduction to Mathematics.” In 1966 the course was taught by NTU math professor Kung-Sing Shih (施拱星). Shih was born in Taiwan in 1918, during the Japanese colonial period, and grew up in Kyoto. He was one of very few Taiwanese to receive a mathematics degree in Japan before 1945; another was Zhen-Rong Xu (許振榮). Both of them returned to Taiwan after 1945 and taught mathematics at NTU. In 1950 Xu went to the United States to work with Shiing-Shen Chern, who at the time was at the University of Chicago. Chern then helped Shih to enter the University of Illinois, where the latter earned a PhD in mathematics in 1953 under the direction of Gerhard Hochschild. Both Xu and Shih returned to Taiwan, Xu to the Institute of Mathematics at the Academia Sinica, and Shih to NTU, where he served as the dean of the faculty of science for ten years.

The textbook for Shih’s “Introduction to Mathematics” course was the original English version of the classic What is Mathematics?, by Richard Courant and Herbert Robbins.8 Jang-Mei enjoyed Shih’s course greatly. “It opened my eyes to what mathematics is, not just calculus and proofs, but other things,” she recalled. “Number theory, topology, complex analysis — I had never seen them before.” Shih tried to impart a sense of what mathematics is really like and how one might think about it, said Winnie. Among the permanent faculty at NTU at the time, “probably he is the one who had the best overall view of mathematics.” A year later, Chuu-Lian took the same course, this time taught by Dong-Sheng Lai (賴東昇), and also with the Courant and Robbins book. Chuu-Lian remembered Lai as an inspiration to the students, who ran their own seminars to study each topic covered in the course.

Another important first-year course was calculus, which in 1970 was taught by Ju-Kwei Wang (王九 逵), an NTU graduate who had earned a PhD in mathematics from Stanford in 1960, under the direction of Karel DeLeeuw. Wang’s lectures were unusual. “Most of the other teachers [at NTU] were teaching the Chinese way, that you have a book, and you copy from the book to the blackboard and you explain a few things,” said Winnie. “But [Wang] was really trying to explain the meaning to you, to make it more lively. To me that was very stimulating.”

In that first year, a subset of the women mathematics majors began

studying together. The regular study group included Alice, Winnie, and

Fan, along with two others:

Shou Jen Hu

(胡守仁), who went on to earn a

PhD at the University of Chicago under the direction of

Melvin Rothenberg,

returned to Taiwan, and spent her career

at Tamkang University; and

Shao-Yun Liu

(劉小詠), who also went to

Chicago for graduate school but died young. When Professor Wang told

the students to hand in solutions to the odd-numbered problems from

the book, the study group would solve all the problems, odd and even.

After working individually, the group would meet. “Someone would say,

I have difficulty [with one problem], then another would say, I have

this idea,” said Alice. “And then we would discuss it together.”

Sometimes they even had long Saturday sessions. “But it was not just

work. We had fun…There was some competition, but on the other

hand, we quickly realized everybody has their own strengths and thinks

differently…We learned from each other.”

One striking aspect about university life in Taiwan at the time is that it was unaffected by the student protest movements that rocked university campuses around the world in the late 1960s. A 1969 New York Times article (“Student activism is rare in Taiwan,” 15 June 1969) datelined from Taiwan stated: “The Chinese Nationalist officials here point out with pride that they have no hippies, no Red Guards, and no radical student movements.” One reason was martial law, which was not lifted until 1988 and which the KMT regime used to repress political opposition.

Immersed in mathematics, the miracle group had essentially no contact with political issues — and little incentive to seek it out. “It was well understood, as long as you don’t touch politics, you can do anything you please,” said Fan Chung. She knew of people who had been accused of being spies for the Communists and wound up in jail. The miracle group learned much more about the reality of the KMT rule after moving to the United States and reading the American news. That “opened our eyes more,” said Fan, “because the propaganda over in Taiwan was very one-sided.”

Bonding for learning and solidarity

The bonding of the women in the classes and study groups was especially important at that time at NTU. Most of the mathematics instructors did not have PhDs and lacked experience in the subject. They knew how to choose current, high quality textbooks, but their lectures were often dry and formulaic. As a result, students learned the material largely by studying on their own or in groups and by working lots of problems.

The female solidarity also helped the women handle the swagger of the men students. In their all-girl high schools, teachers had praised the girls’ mathematical prowess and told them they could do anything. NTU was different. Fan Chung remembered a freshman orientation session where several male students “jumped to the blackboard and started to tell us about all the books that are good for preparation” for the math major. “It was very intimidating,” she said. “They wrote down all these names of mathematicians and books that we had no idea about.”

But the women worked very hard, and within one semester, they were the ones with the best scores. “That greatly helped our confidence in ourselves,” Fan remarked. “Because in mathematics, it doesn’t matter if you are short or you are a woman… The math score doesn’t lie, right? That’s the nice part about mathematics. You can prove yourself.”

There was posturing by some of the men students who, when they did well, saw their success as due to intrinsic smarts. The women students by contrast saw success more as a result of hard work and perseverance. In addition, they served as an inspiration for each other. Jang-Mei did not study much with the other women but drew confidence from their collective efforts. “I saw other people could make it…and I thought I can make it,” she said. “I just kept on going.”

Only one of their courses, in Galois theory, was taught by a woman. This was Tzee-Nan Kuo (郭子 南), a visiting professor who was an NTU graduate herself and had earned a PhD in mathematics in 1966 from the University of Chicago, under the direction of Jonathan Alperin. Kuo “was a really good teacher,” Chuu-Lian said. “She had everything in her head and lectured very well… I remember I really wanted to perform well in that course.” Too shy to speak to Kuo, Chuu-Lian tried to impress her by working the homework problems exceptionally well. Kuo “really inspired me,” Chuu-Lian recalled. “I thought, ‘yeah, I would like to be a professor like her’.” Kuo left academia a few years later and had a career working for the United States government.

Mei-Chi Shaw entered NTU in 1973, which was a few years after the rest of the miracle group had graduated. Taiwan’s economic situation was improving by then, and its industrial sector was growing rapidly. Students were also becoming less idealistic. When the other miracle women had started at NTU, “math and physics were everybody’s dream department,” said Mei-Chi. “By the time I went to college, everybody wanted to go into electrical engineering.” Many of her fellow mathematics majors had not listed that subject as their first choice for a major. Indeed, several of the nine women math majors had hoped to be in an engineering discipline and settled for math as their second or even third choice. By this time NTU had one woman mathematics professor, Sou-Yung Chiu (邱守榕), who had received her PhD in 1970 at Northwestern University, under the direction of Kenneth Roy Mount. She encouraged Mei-Chi and helped to counteract the attitude conveyed by some of the male students and professors that mathematics is not for women.

Mei-Chi did not overlap with any of the other members of the miracle

group at NTU. But she heard about them. People in the mathematics

department spoke with awe especially about Winnie Li, because at the

time she had a position at Harvard University, as a Benjamin Peirce

Fellow. One of Mei-Chi’s teaching assistants had started as a math

major in 1966 along with Winnie, Alice, Fan, and Jang-Mei. He recalled

that those four, plus six other female mathematics majors,

consistently placed at the top. This was not long after the release of

a movie whose title translates as The Fourteen Amazons

(十四女英豪). The movie, made by

Hong Kong film producer Run Run Shaw, tells the story of the valor of

fourteen Chinese women warriors. Mei-Chi’s teaching assistant “always

joked that there were ‘Ten Amazons’ in his class, and they ranked

number 1 to 10,” Mei-Chi said. “All the boys had to fight for number

11.”

A sense of freedom, and of obligation

When Jang-Mei Wu was growing up, her parents worked very hard just to provide the family with basic necessities. Still, Jang-Mei’s mother found time to play ping-pong on the floor with the kids; her father taught her to use an abacus and memorize classic Chinese poetry. Despite their straitened circumstances, Jang-Mei’s parents created an atmosphere in which she felt free to do what she found fun and interesting. They did not pressure her to take up a profession — medicine being the canonical example — that would ensure financial security. “They didn’t push me,” Jang-Mei said, describing their attitude as: “You do well, and if you don’t make much money, it’s okay.”

The six women in the miracle group felt this freedom from the pressure to seek wealth and material possessions. They were aiming for something more exalted. In doing so, they also felt a deep obligation to make the most of the opportunities available to them. “All of us growing up during that time had to strive,” said Mei-Chi Shaw. “We had to make it worthwhile for our parents. I always had the feeling that I cannot fail, because of the hardship they endured.”

It was only in 1976 that Taiwan established its first doctoral program in mathematics. So it was with a sense of both freedom and of obligation that the miracle women, after graduating from NTU, left the island they knew as home and moved across the ocean to the United States, to pursue graduate study in mathematics.

Several of the women finishing in 1970 felt that their chances of getting accepted by a graduate program in the United States would be higher if they applied to different places. So they decided to coordinate their applications. As the number one student, Winnie Li got first choice of where to apply, the number two student got to choose next, and so on. Alice Chang spoke of this method as a way of “honoring” each other. “We cooperated,” she said. “Without a good friendship, I think this would not happen. Later on I realized this was very special.”

Winnie ended up putting off graduate school and staying in Taiwan for one year, so Alice applied to, and was accepted by, Winnie’s first-choice school, the University of California at Berkeley. They became classmates when Winnie was accepted the following year. Fan Chung went to the University of Pennsylvania, and Jang-Mei Wu to the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. The following year, in 1971, Chuu-Lian Terng was accepted by Brandeis University. Six years later, Mei-Chi Shaw went to Princeton University. Mei-Chi’s only-woman status in the Princeton math department ended when Chuu-Lian became an assistant professor there, in 1978. The two have been close friends ever since.

The miracle group were among the very few women going into mathematics in the 1970s. In 1974 — the year Alice, Winnie, Fan, and Jang-Mei finished their PhDs — women earned just 9 percent of the approximately 1,000 mathematics doctorates awarded in the United States. The rate was 10 percent when Chuu-Lian finished the following year; by 1981, the year Mei-Chi finished, it had risen to 16 percent. In the past ten years or so, it has hovered around 30 percent.

After finishing their degrees, the miracle group faced a tight academic job market in mathematics in the United States. Nevertheless within a few years they all managed to find permanent jobs in good institutions. They were all in academia, except for Fan Chung, who joined the research staff of Bell Laboratories; twenty years later, after the breakup of the labs, she moved into academia with ease. All are active and prominent researchers, each in a different area of mathematics: Alice Chang in geometric analysis, Winnie Li in number theory, Jang-Mei Wu in complex analysis and potential theory, Chuu-Lian Terng in differential geometry, Fan Chung in discrete mathematics and combinatorics, and Mei-Chi Shaw in several complex variables.

Shiing-Shen Chern, a beloved mentor

Launched in 1962 and still published today, Biographical Literature has served as something of a repository for the history of Taiwan, told through the lives of people connected to it. Chern made a few contributions to the magazine, including a memoir about his own life in mathematics, published in 1964 when he was in his early fifties. At that time, he’d been a tenured professor of mathematics in the US (at the University of Chicago and then Berkeley) for 15 years. His ties to Taiwan remained strong, however, and his formative influence on the miracle group was profound.

In 1945, Chern helped to found the Institute of Mathematics of the Academia Sinica in Nanking, the then-capital of the Republic of China. In 1948, the intensification of the Chinese civil war compelled him to leave for the United States. That same year, the institute moved to Taiwan, which has been its home ever since. Through numerous visits to Taiwan, including to the institute he helped found, and through many personal interactions, Chern lent a helping and encouraging hand to many mathematicians from Taiwan. Another connection to Taiwan came through the marriage of his daughter May to superconductivity pioneer Paul Ching-Wu Chu (朱經武), who was born in China and spent his early years in Taiwan.

Although Chern was a professor at Berkeley when Alice Chang and Winnie Li were graduate students there, he was not the formal advisor of either of them. But he was a beloved mentor to both. Winnie remembered when she told Chern she might want to go into algebra. “He said, ‘Well, in algebra there are only two areas. One is algebraic geometry, the other one is number theory’,” she recalled. “At the time, Berkeley did not have algebraic geometers, so I should go into number theory. That’s how I happened to do number theory!” Of course, algebra has subfields other than the two Chern named. But “in a sense he was right, from the viewpoint of importance,” said Winnie. “He was thinking about the big structure.”

Alice has vivid memories of Thanksgiving dinners at Chern’s home and of chatting with him while walking across the campus. “We learned from him not only academically but also through his open, optimistic attitude toward other people and life,” she said. Her own research in geometric analysis has been deeply influenced by Chern. One of the main topics of her research in conformal geometry has been the study of the 4-dimensional Chern–Gauss–Bonnet formula. “I appreciated his work much more, and increasingly with time, after I graduated from Berkeley,” she said.

Chuu-Lian Terng, who got to know Chern while she was a postdoc at Berkeley, was especially close to him. In a memorial article about him, she wrote of his instinct for deep and important questions, which inspired her to move her research into new directions after her PhD thesis. Chern’s support and encouragement were very important to her. “He never gave me false hopes,” Chuu-Lian wrote, “but made it clear to me that hard work counts and that being a mathematician was an enjoyable profession.”

The other three miracle women — Fan Chung, Mei-Chi Shaw, and Jang-Mei Wu — knew Chern less well but were still influenced by him. Mei-Chi remembered him as friendly and unpretentious, generous with his praise and support. She also felt his influence through the article in Biographical Literature, which put his imprimatur on their achievements. “It was such an encouragement to me,” she said. “He didn’t have to write that article, you see? He was a different kind of mathematician and a different kind of person, and that’s why his influence is so great,” not only within his own field of geometry but in other areas as well. “Chern went out of his way to encourage women,” she added. “We were really lucky to have such a mentor.”

For Jang-Mei Wu, the article helped her family understand what she’d done with her life. “It was very hard to explain to my parents what I was doing in my office on most days, which was to just sit and think and throw a lot of scratch paper into the waste basket,” she said. “In some way that article answered their questions.” Her father had passed away by the time of publication, but her mother and sister enjoyed reading it. The occasion also renewed her appreciation of her parents. “In many ways, their quiet support, in an unassuming and not pushy way, gave me a lot freedom to pursue my interests.”

A gift from mothers to daughters

Chuu-Lian Terng’s mother grew up in Hunan in a wealthy family, with servants doing all the housework. In Taiwan, life was utterly different. “I remember [my mother] doing the laundry,” Chuu-Lian recalled. “We didn’t have a washing machine, so she had to do it by hand on a washboard… My God, it was something.” Daughters would usually help with such chores, but Chuu-Lian was not allowed to. “She didn’t want me to do any housework,” Chuu-Lian recalled. “She didn’t even let me wash dishes. She said, ‘You study. I want you to get a good education, be independent. I want you to have a good marriage, but you have to be able to depend on yourself.’ ”

Having endured a wrenching dislocation from their homeland, the mothers of the miracle group faced a much more difficult life in uncertain times in a new land. How did they adapt? Winnie Li said that, while her mother would sometimes talk about “the good old days,” the prevailing mindset was practical. “This is the life, they take it, they accept it,” Winnie said. In this acceptance, the mothers of the miracle group embodied for their daughters an ethos of hard work, persistence, and resilience.

The miracle group developed and drew on these qualities to succeed. And because they saw hard work as the route to success, failure looked less scary and was something from which one could recover — by working yet harder. For the favored son who expects his innate talent will carry him to the heights his family has set for him, a fall might be devastating. The miracle group labored under no such expectations. “You work as hard as you can, and you see what happens,” said Mei-Chi Shaw. “Our egos are not that big… So we are less afraid of failing than others.”

Their indefatigable efforts, made with no sense of entitlement, served the exalted ideals they pursued: learning, understanding, scholarship, mastery, wisdom, freedom. Their triumph is sweet.

Miracle group honors (by individual)

Sun-Yung Alice Chang

1974 Ph.D. University of California Berkeley, “On the structure of some Douglas subalgebras”.

1979 Fellowship, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (1979–1981).

1986 Invited speaker, International Congress of Mathematicians in Berkeley.

1995 Ruth Lyttle Satter Prize in Mathematics (American Mathematical Society).

1998 Guggenheim Fellowship.

2002 Plenary Speaker, International Congress of Mathematicians, Beijing.

2008 Member, American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

2009 Fellow, National Academy of Sciences.

2012 Fellow, Academia Sinica.

2015 Fellow, American Mathematical Society.

2018 Emmy Noether Lecturer, International Congress of Mathematicians, Rio de Janeiro.

2015 Outstanding Alumni Award, National Taiwan University.

2019 Fellow, Association for Women in Mathematics.

Fan-Rong King Chung

1974 Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, “Ramsey numbers in multi-colors and combinatorial designs”.

1990 Allendoerfer Award (Mathematical Association of America).

1994 Invited address, International Congress of Mathematicians, Zurich.

1998 Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

2009 Emmy Noether Lecture, Association for Women in Mathematics.

2015 Fellow, Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

2016 Academician, Academia Sinica.

2017 Euler Medal (Institute of Combinatorics and its Applications).

2022 Fellow, Network Science Society.

Wen-Ching Winnie Li

1974 Ph.D. University of California, Berkeley, “Newforms and functional equations”.

1981 Fellowship, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (1981–1983).

2010 Chern Prize in Mathematics (International Congress of Chinese Mathematicians).

2012 Distinguished Professor of Mathematics, Penn State University (in recognition of exceptional teaching, research and creativity).

2012 Fellow, American Mathematical Society.

2015 Noether Lecture, Association for Women in Mathematics.

2018 Special Contribution Award (Taiwanese Mathematical Society).

Mei-Chi Shaw

1981 Ph.D. Princeton University, “Hodge theory on domains with cone-like or horn-like singularities”.

2012 Fellow, American Mathematical Society.

2019 Stefan Bergman Prize (American Mathematical Society).

Chuu-Lian Terng

1976 Ph.D. Brandeis University, “Natural vector bundles and natural differential operators”.

1980 Fellowship, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (1980–1982).

1997 Humboldt Senior Scientist Award (Alexander von Humboldt Foundation of Germany).

1999 Falconer Lecturer, Association of Women in Mathematics / Mathematical Association of America.

2006 Invited Address, International Congress of Mathematicians, Madrid.

2018 Fellow, Association for Women in Mathematics (inaugural class).

Jang-Mei Wu

1974 Ph.D. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, “An integral problem for positive harmonic functions”.

1990 Invited Address, American Mathematical Society.

1992 Erskine Fellow, University of Canterbury, New Zealand.

2006 Frederick and Lois Gehring Professor, University of Michigan.

2020 Fellow, American Mathematical Society.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the six women of the miracle group — Sun-Yung Alice Chang, Fan Chung, Wen-Ching Winnie Li, Mei-Chi Shaw, Chuu-Lian Terng, and Jang-Mei Wu — for sharing their stories. I also gratefully acknowledge the help of J. Megan Green (University of Kansas), Hsiao-Ting Lin (Hoover Institution, Stanford University), Sheila Newbery (Mathematical Sciences Publishers), and Hung-Hsi Wu (Department of Mathematics, University of California, Berkeley). Responsibility for the accuracy of the article is my own.