by Arthur Jaffe

Arthur Jaffe, president of the American Mathematical Society from 1997 to 1998, reminisces about his forty-year relationship with Raoul Bott as colleague, friend, and confidant.1

I first encountered Raoul Bott in 1964. While a student in Princeton I came across the beautiful Bott–Mayberry paper on matrices and graphs and used their representation of a determinant in analyzing a problem in quantum theory. But that experience did little to prepare me for our first face-to-face meeting. Raoul’s personality and spirit struck me with awe; it left an indelible mark in my memory.

Later we became colleagues, and it was then that Raoul evolved into a very special and dear friend. We shared many mathematical discussions together. We also spent hours talking about the world, laughing over an amusing story, listening to music, or sharing a meal with a good wine.

Raoul had always had an interest in physics, but that had some unusual twists. For example, when Raoul learned of normal ordering (a simple form of renormalization), he used to ask me if it could have something to do with the resolution of singularities in algebraic geometry, still an intriguing question.

Raoul described discussions he had with his neighbor Chen Ning Yang during 1955–57 at the time Raoul was a visitor at the Institute for Advanced Study. While they discussed many things, connections were not on the agenda. Only later did one realize their central role in Yang–Mills theory. In the late 1970s we had a long discussion while driving together from Cambridge to an AMS summer meeting in Providence about how important it was to have a good dictionary to translate between gauge theory as physics and differential geometry as mathematics in order for people in the two subjects to communicate.

While I had first met Raoul in a mathematics conference before I came to Harvard in 1967, I really got to know Raoul well during the Les Houches summer school in 1970. Cécile DeWitt had established a famous summer school of theoretical physics after World War II; it was located in a small French village in the Alps, not far from Mont Blanc. The only problem about trying to work in Les Houches was the distraction of a striking view of the Aiguille du Midi. In 1970 the focus of the school was mathematical quantum field theory. Raoul was officially an “observer” at the school, sent by the Battelle Institute, which sponsored the event.

Cécile had an interesting philosophy about Les Houches: in order to maximize interaction, the participants at Les Houches should come at the beginning of the meeting and remain there until the end. And this school lasted two full months! Both in the lectures and at the meals in the large dining room, the participants interacted like a large family for sixty days. Raoul brought his wife, Phyllis, and their three young girls, and their son, Tony, also visited on occasion. So, over the course of that summer, I really got to know the Botts. In fact, George and Alice Mackey and their daughter, Ann, were there too, so there was a big contingent from Harvard.

After returning to Cambridge that fall, I began a mathematical physics seminar at which Raoul became a regular attendee. Several of the students from Les Houches also came to Harvard. Raoul enjoyed them all but became especially fond of Konrad Osterwalder, who eventually spent six years in Cambridge and became one of Raoul’s regular confidants before he left for the E.T.H. Zürich.

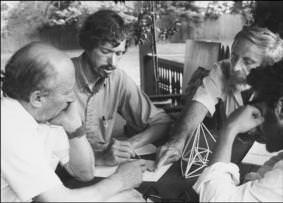

In 1976 I helped a friend in Paris organize a summer school in Cargèse, Corsica, where I had been during the summer of 1964. The experience left me with a lasting impression of the beauty and history of this Greek-French village by the Mediterranean Sea. The success of the resulting gathering led to our having five more schools in Cargèse. The second school in 1979 brought together an interesting group of mathematicians and physicists, including Raoul, Michael Atiyah, Jürg Fröhlich, Jim Glimm, Gerard ’t Hooft, Harry Lehmann, Isadore Singer, Kurt Symanzik, Ken Wilson, Edward Witten, and Jean Zinn-Justin. The accompanying photographs (Figures 16 and 17) show that Raoul was in good form in the school: not only did he give beautiful lectures but he animated less formal moments. The combination of the productive and interactive scientific atmosphere, along with an inviting beach, brought Raoul and Phyllis back to Cargèse in 1987 and 1991.

Originally I had been appointed professor of physics at Harvard, although some of my courses were cross-listed in mathematics. But in the spring of 1975 the mathematics department invited me to become a member. Raoul was chairman at the time, and I recall the pleasure with which he described to me that vote. Raoul also enlivened the ensuing faculty meetings following Thursday lunch at the Faculty Club. Until sometime in the 1980s, the department decided on teaching assignments in an old-fashioned way: discuss this at a faculty meeting, which always seemed to have full attendance! The chair wrote on the board a list of necessary courses; the persons present filled in their names in order of seniority in the department. This gave the more senior members of the department an elevated status, in which Raoul amusedly reveled.

In 1978 Raoul and Phyllis became Masters of Dunster House. I had been a happy member of Lowell House ever since some students brought me there during my first year at Harvard. But Raoul asked me to switch and be with him at Dunster, which I eventually did. I brought along a few of my own collaborators, and I have many fond memories of evenings with friends at Dunster: with students and with scientific colleagues in the dining hall, with members of the “Senior Common Room” at their regular meetings, at the Dunster concerts, at the Red Tie dinners, and during many other occasions in the master’s residence with Raoul and Phyllis. Raoul sometimes had his mathematical friends stay in Dunster, such as Fritz Hirzebruch or Michael Atiyah, and he would enjoy letting us know when some mathematician friend of his might be making an unannounced visit to Cambridge.

With our frequent intersection at Dunster House, we often made plans to do things together. We both enjoyed music and often had met at undergraduate concerts. I recall our discussing the concert at Sanders Theater when Yo-Yo Ma’s undergraduate quartet played Brahms. I went with Raoul to the first performance that the Tallis Scholars sang in Boston in a concert at the Church of the Advent. Much after that, I sat with Raoul in his music room in his apartment on Richdale Avenue while he played Bach on his Steinway. Later in that room we discussed the differences between recordings of the Goldberg Variations made by Glenn Gould and András Schiff. (András is another genius from Hungary whom I admire. I have also come to know him as a friend, and I wish that I could have introduced Raoul and András to each other, for they certainly would have hit it off well.)

Raoul did not always remember the seminar schedule, so he enjoyed having his office across from the main seminar room in the department. One felt in the middle of things with people passing by, and with the glass window along the hall corridor, one could always see at a glance what seminars were taking place.

Raoul could turn up at the most unusual time or place. When I married in 1992, Raoul was an usher in the wedding. I recall how proud he was to escort my daughter, Margaret. And I was not surprised in the summer of 2002 to arrive at the airport in Vienna and find Raoul and his granddaughter, Vanessa Scott, there too. They were on their way to make a film about Raoul’s life, a wonderful story I saw in 2006.

Raoul’s life turned upside down when Phyllis had a stroke. He began to spend every day with his Mac computer at Youville Hospital in Cambridge, where Phyllis was recuperating. For a while George Mackey was nearby in the same hospital. During those days Raoul often came to my home for dinner. We sat around the kitchen table over swordfish or bluefish from the broiler. The conversation sometimes turned to music. Raoul admired the virtuosity of my harpist friend, Ursula. Many people regarded Raoul as a father figure, but Ursula was drawn to him for the empathy he expressed for others in need of assistance and for his understanding of the problems of the world. Raoul explained that life would be much easier for him and Phyllis in California rather than in their multistory townhouse. In Cambridge many friends were sad to see them go.

The mathematics department held a dinner in the Faculty Club the night before Raoul and Phyllis left Cambridge. After most other persons went home that evening, I gave Raoul a bottle of excellent Bordeaux. Occasionally I spoke with Raoul by telephone, a nice link between Cambridge and Carlsbad, California. It was wonderful to hear his voice and to get some news. During one of those conversations late in 2005, Raoul let me know that he had left that bottle of Bordeaux with his daughter Candace in Cambridge. She was bringing it to California the next day so he could share it during a small family reunion. At the time I did not realize how Raoul was telling me that his end was upon him. Shortly afterward I cried at the news.