by Oleg Lazarev

Yasha-isms

In grad school, this lighthearted, playful atmosphere pervaded the whole cadre of symplectic geometers around Yasha, which at one point had seven grad students, including the notable prankster Kyler Siegel. One year on April 1st, I received an email from Yasha saying that he did not want to be my advisor anymore and that instead I ought to go to Sweden and work with another professor there. Although I was initially surprised, I realized that it was April Fool’s day and played along, saying I would be glad to leave. At this point, Yasha replied saying that he wasn’t the one that sent the email. After several increasingly ridiculous emails, we came to the conclusion that another student had spoofed Yasha’s email and had pranked both of us! Yasha was quite pleased by the prank and impressed by the ability of the prankster, leaving me envious that I hadn’t devised the prank myself.

As an advisor

I also recall having to ask Yasha to be my advisor twice. The first time I asked, when I was already doing a reading course with him and another professor, he replied that we could keep meeting even if he wasn’t my official advisor. In hindsight, I see that this was a kind gesture that would grant me more freedom, but at the time his response left me a bit concerned about the status of our relationship. So I went back and asked him again. At this point, he laughed and said, “Yes of course, we’re already working together! What do you want? A handshake?” He shook my hand and we began working in earnest.

There was quite a bit of flexibility working with Yasha, pun intended. After reading Milnor’s h-cobordism book (which I think Yasha required many of his students to do), I worked on some questions about augmentation varieties and Legendrian knot contact homology, which I had started reading about before working with Yasha. He was happy to listen and provide feedback. However I eventually realized that this topic was something Yasha had thought about (and helped found as a subfield) many years ago but that he had not kept up with the latest developments. I asked Yasha if we could switch to a topic he was more familiar with at the moment. He proposed that I think about flexible Weinstein domains, on which topic he had just written a book with Kai Cieliebak, and that I focus on their contact boundaries. Eventually I solved the main problem that he proposed and was writing up the proof. In the process, I had to describe a class of contact manifolds and decided to call them “quasi-good” since there was already a class of contact manifolds called “good” and mine seemed to obey a weaker property that sufficed for my purposes. In a typical Yasha-ism, he replied, “Quasi-good is a quasi-good name.” Later, I renamed these contact structures “asymptotically dynamically convex”, a more descriptive (and serious-sounding) name. The episode made me realize that choice of terminology should also require serious mathematical thought.

Yasha was also happy to introduce people to each other and promote collaborations. Sometime in the middle of grad school, Yasha asked me to join his meetings with Sheel Ganatra, a postdoc at the time. We started talking about flexible Lagrangians, a variant of my thesis work on flexible Weinstein domains. After we made some progress and had an idea of the proof, I wanted to work out the details more carefully. However, a week later, Yasha produced a first draft sketching the proof we had figured out. I was a bit surprised (particularly since I thought that Sheel and I, as the junior collaborators, would be responsible for the bulk of the writing). This first draft had a lot of errors and not quite correct definitions, but it provided a good framework and starting point for our paper. Later we worked out many of the details and added new results, but this top-down approach of sketching out the overall picture first proved much more efficient and enlightening. This episode also reflected Yasha’s extremely energetic and optimistic personality. I remember him saying, “If you want to learn something, you can do it in two months” — which, in typical fashion, was a mix of outrageous and inspiring.

Rigidity vs. flexibility

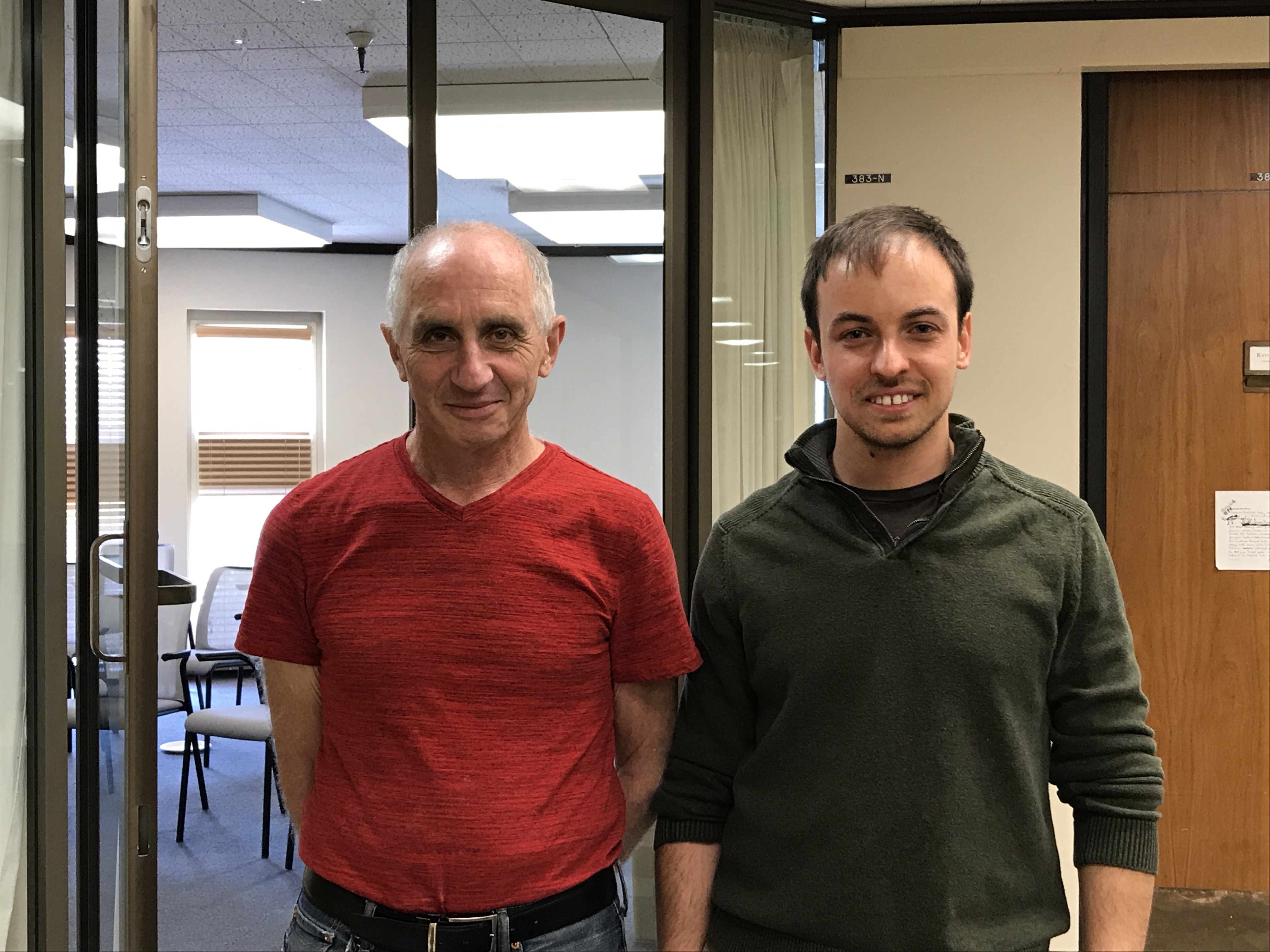

The author received his PhD from Stanford University in 2017 under the supervision of Yasha Eliashberg. He is currently an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts Boston.