by Rob Kirby

The Schoenflies conjecture

Let \( f:\mathbb{S}^{n-1} \times [-1,1] \to \mathbb{S}^{n} \) be an embedding (not necessarily smooth or PL). Then, both closed complements of \( f(\mathbb{S}^{n-1} \times 0) \) are homeomorphic to the \( n \)-ball \( \mathbb{B}^{n} \). In fact, \( f|_{\mathbb{S}^{n-1} \times 0} \) extends to an embedding of \( \mathbb{B}^{n} \) on either side.

This positive answer to the Schoenflies Conjecture was proved in 1958 by Barry [1], but with an added hypothesis that \( f \) is simplicial (or smooth) on some open set. Then Mort Brown gave a different proof [e4] not using the hypothesis, and then Marston Morse [e7] removed the hypothesis from Barry’s proof.

Barry and Mort shared the second round of Veblen Prizes in Geometry in 1966, at that time the highest prize in topology other than the Fields Medal.

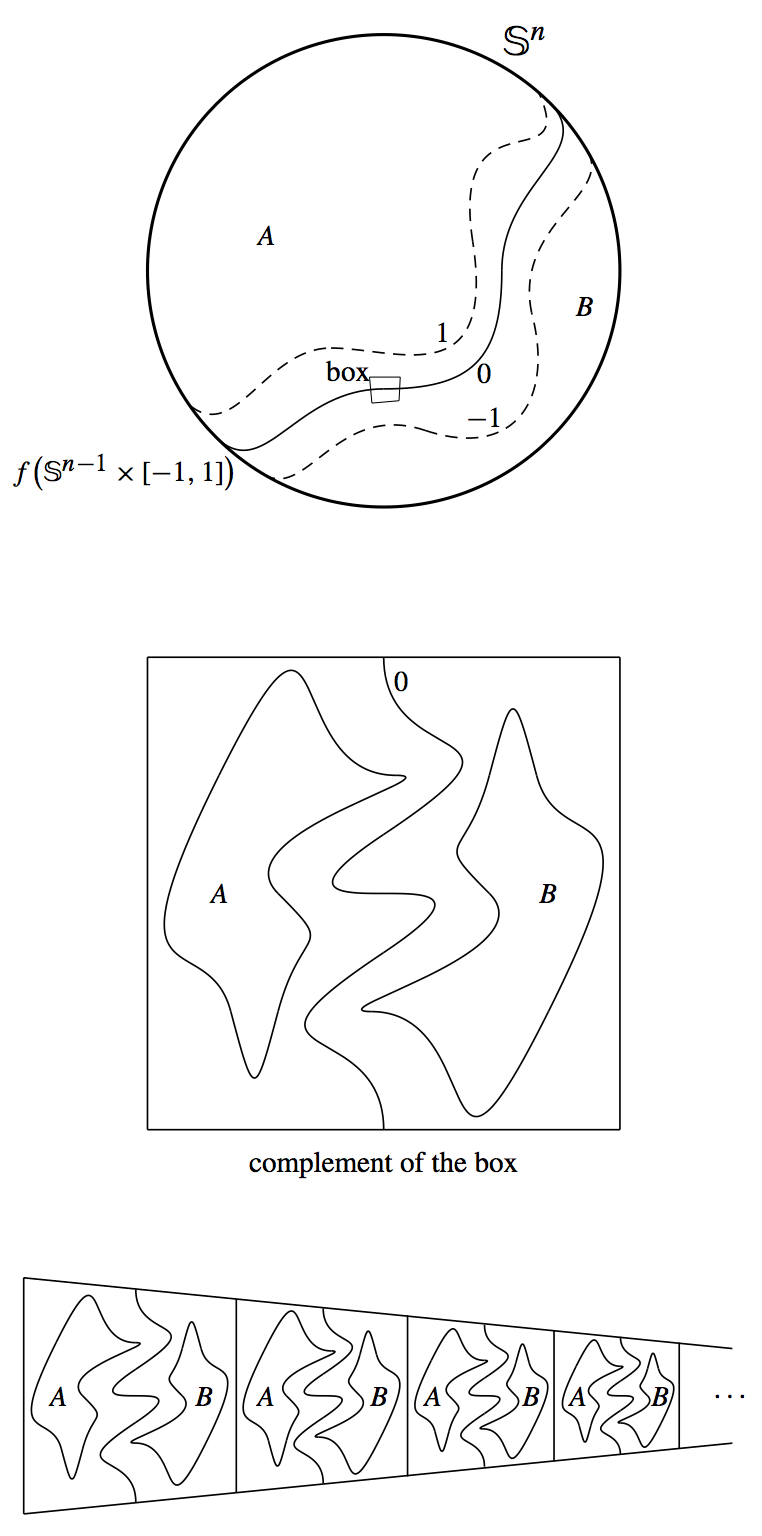

Barry’s proof was startling to say the least. The Mazur swindle, as it was sometimes called, involved the infinite product \( ABABABAB\cdots \). If \( AB = \operatorname{Id} = BA \), and if the infinite product makes sense under different ways of assigning parentheses, then \begin{align*} A &= A(BA)(BA)(BA) \cdots\\ & = (AB)(AB)(AB) \cdots = \operatorname{Id}. \end{align*} This formalism does make sense in Barry’s setting, where \( \operatorname{Id} = B^n \), \( A \) and \( B \) are approximately the complements of \( f(\mathbb{S}^{n-1} \times 0) \), and \( AB \) and \( BA \) are boundary connect sums (see the figure, where we are looking at \( \mathbb{S}^{n} \) minus a cube representing a portion of the open set on which \( f \) was assumed to be PL or linear). You now have most of the ideas and are ready to read (or prove yourself) Barry’s beautiful short announcement in the Bulletin of the AMS.

Barry and Mort’s proof opened the door to the study of topological manifolds, which had been nearly untouchable until this time. Within ten years, great progress had been made: Brown’s collaring theorem [e4]; Milnor [e14] on microbundles; Jim Kister’s proof [e13] that topological manifolds have tangent bundles; Brown and Gluck’s work [e9], [e11], [e12], [e10] on stable homeomorphisms and the annulus conjecture; Sullivan on the Hauptvermutung [e18], [e29]; Chernavskii [e20] and Edwards–Kirby [e22] on local contractibility of the space of homeomorphisms of a manifold and the isotopy extension theorem; culminating with Kirby–Siebenmann [e23] for the existence and uniqueness of triangulations of manifolds (dim \( \neq 4 \)), using Wall’s nonsimply connected surgery machinery [e21].

Mazur manifolds

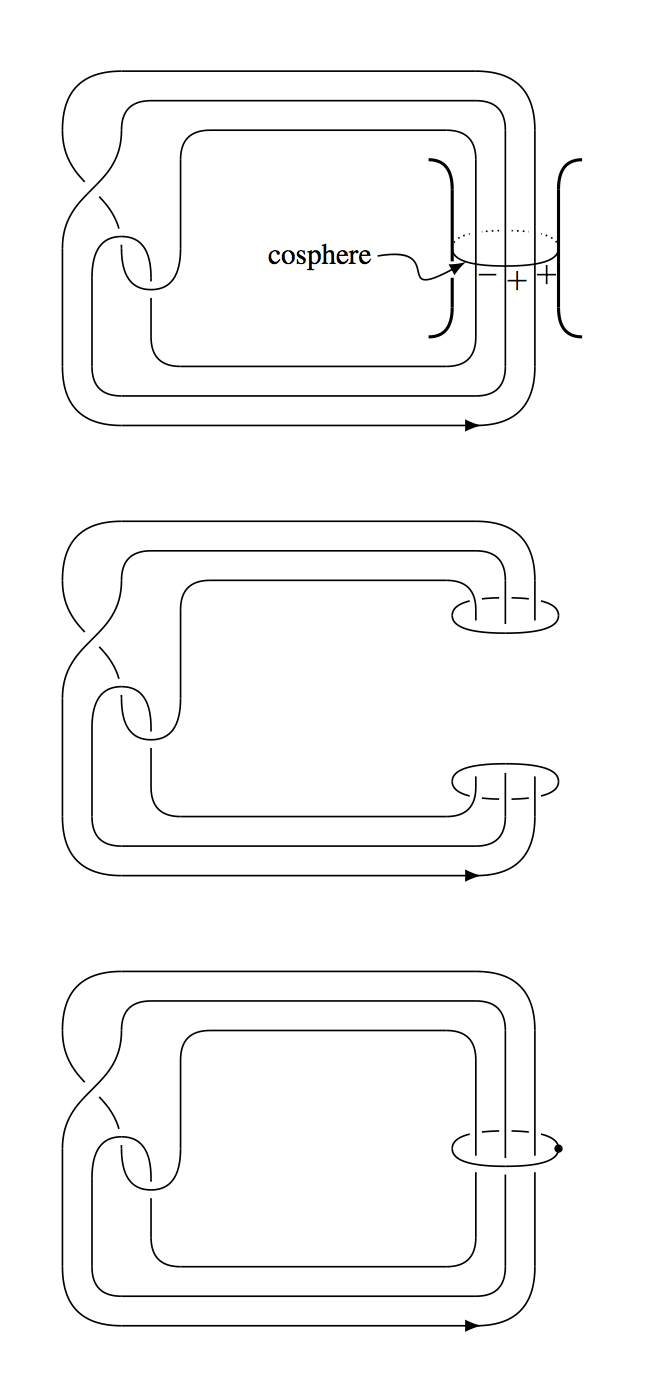

In an Annals paper [2], Barry constructed a smooth contractible 4-manifold \( W^4 \) by adding a 1-handle to the 4-ball and then a 2-handle to a circle which went over the 1-handle algebraically once, but geometrically three times (see the next figure, where the 1-handle is drawn in three different ways, i.e., the whole 1-handle, just the “feet” of the 1-handle, or with a dotted circle to indicate that the attaching circle of the 2-handle is going over the 1-handle).

Thus the 2-handle does not geometrically cancel the 1-handle, but it does so homotopically, and the result, while not the 4-ball \( \mathbb{B}^{4} \), is nonetheless contractible with a homology 3-sphere as boundary.

With hindsight, what’s the big deal? Such handlebody theory is practically trivial these days. But not so in 1960. Markov had only recently proved his big theorem on nonrecognizability of smooth 4-manifolds [e6] by equally elementary handlebody theory. And Smale had just proved the \( h \)-cobordism theorem with handlebody theory.

But the real point to the paper was to give a contractible 4-manifold, not \( \mathbb{B}^{4} \), whose product with the interval is diffeomorphic to \( \mathbb{B}^{5} \) (Poénaru independently also gave examples [e5]). This is to be compared with famous examples of Bing and others of 3-dimensional spaces (not manifolds) whose products with \( \mathbb{R} \) are homeomorphic to \( \mathbb{R}^{4} \); e.g., [e3].

Barry’s examples came to be known as Mazur manifolds ([e24], whose authors were unaware of Poénaru’s examples);1 they appeared in many places but most remarkably as Akbulut’s “corks,” as we will describe now.

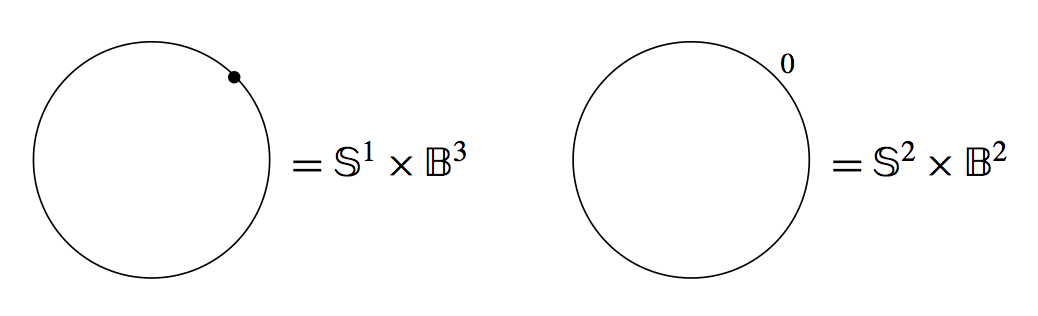

Consider the Mazur manifold drawn in this figure, with the 1-handle denoted by a circle with a dot on it. The point to the dotted circle notation (due to Akbulut) is that, if one surgers the obvious circle (which replaces a neighborhood of the circle with a disk-neighborhood of the 2-sphere), then that 2-sphere arises by adding a 2-handle to the dotted circle with framing zero. It is a different 4-manifold after surgery, but it has the same boundary because the surgery took place in the interior. For example, \[ \partial(\mathbb S^1\times\mathbb B^3) =\mathbb S^1\times\mathbb S^2=\partial(\mathbb S^2\times\mathbb B^2) .\]

Akbulut proved [e26] that this smooth involution of the boundary does not extend smoothly over the interior of the Mazur manifold (the contractible 4-manifold obtained by surgering either of the 2-spheres, arising from the 0-framed circles), although it does extend to a homeomorphism using Freedman’s work [e25]. This remains the smallest and most easily described 4-manifold with two different smooth structures, relative to boundary.

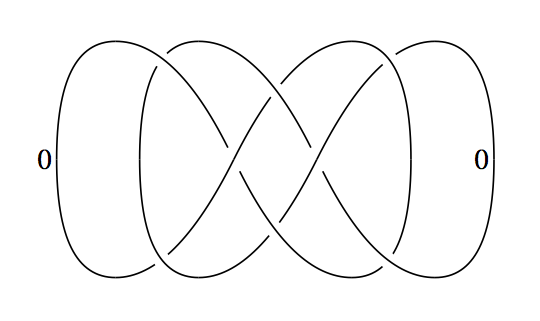

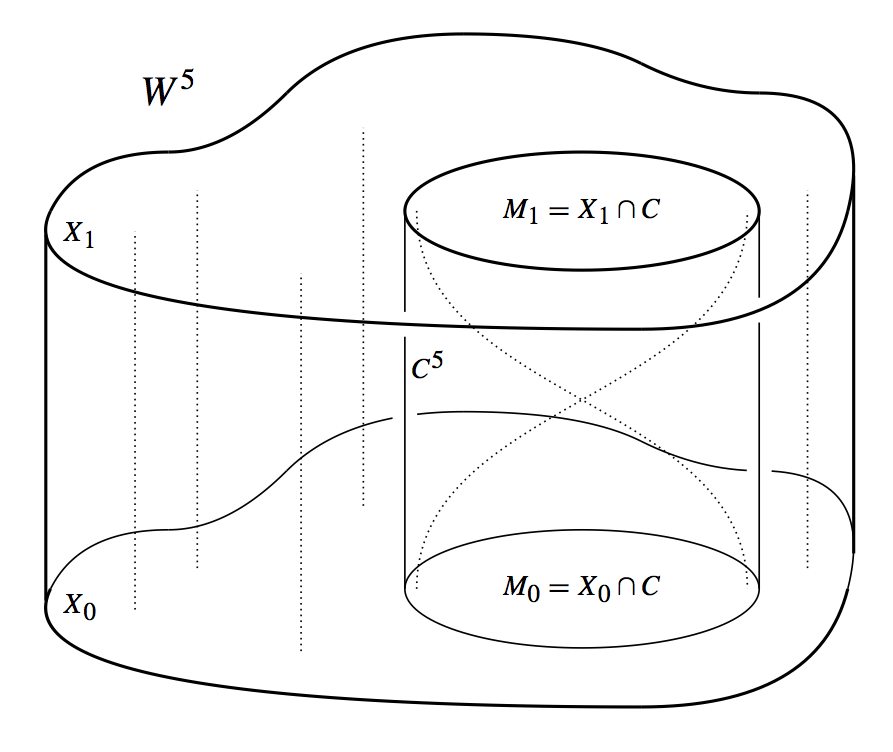

Even more is true. Any two simply connected, homotopy-equivalent 4-manifolds, \( X_0 \) and \( X_1 \), are \( h \)-cobordant [e15]. It was shown [e27], [e28] that the \( h \)-cobordism \( W^5 \) is a product, away from a “cork” \( C^5 \); see the next figure. The cork \( C \) is a contractible 5-manifold, diffeomorphic to \( \mathbb{B}^{5} \), and also diffeomorphic to \( M_0 \times I \) and \( M_1 \times I \), where \( M_i = X_i\cap C \). The 4-manifolds, \( M_0 \) and \( M_1 \), are generalized Mazur manifolds, in that they are constructed with symmetric links of unknots, all framings zero, with pairs linking each other once and the other components zero times.

One or the other of a pair may be surgered, that is, given a dot, and thus describes a generalized Mazur manifold. When crossed with an interval, the crossings disappear and the 5-manifold, \( C \), becomes trivial: \( \mathbb{B}^{5} \). The difference now between \( X_0 \) and \( X_1 \) is that they are diffeomorphic outside the Mazur manifolds, and the Mazur manifolds are sewn in by two different gluing diffeomorphisms whose difference is the involution arising from the symmetric link.

Thus, generalized Mazur manifolds are key to understanding exotic smooth structures on simply connected 4-manifolds.

Tangential homotopy equivalences

A tangential homotopy equivalence (called a “differential homotopy equivalence” in Barry’s paper [3]) is a homotopy equivalence \[ \varphi:M_1^n \to M_2^n \] which induces an isomorphism of stable tangent bundles, \[ \varphi^* T(M_2)\oplus \mathbf{1}_k \cong T(M_1) \oplus \mathbf{1}_k ,\] where \( \mathbf{1}_k \) denotes the rank-\( k \) trivial bundle and \( M_i \) are smooth compact manifolds. Barry then shows that \( M_1 \) and \( M_2 \) are tangentially homotopy equivalent if and only if they are stably diffeomorphic, i.e., \( M_1 \times \mathbb{R}^{k} \) is diffeomorphic to \( M_2 \times \mathbb{R}^{k} \) for \( k \geq n+2 \).

A proof with generalizations to noncompact manifolds, either differentiable, PL or topological, and with similarities to the Mazur swindle in his proof of the Schoenflies conjecture, was given in [6] and independently in [e16].

An interesting point is that the tangential homotopy equivalence is not required to be a simple-homotopy equivalence even in the nonsimply connected case, for, as Barry points out, the lens spaces \( L(7,1) \) and \( L(7,2) \) are tangentially homotopy equivalent but not simple-homotopy equivalent, and are never diffeomorphic (nor PL homeomorphic) even after crossing with the \( k \)-ball \( \mathbb{B}^{k} \), for any \( k \) [e1]. Yet, after crossing with \( \mathbb{R}^{k} \), they are diffeomorphic.

Here is a sketch of a method to prove Barry’s theorems, which is in the same spirit as his method. Starting with the tangential homotopy equivalence \[ \phi:E_1 \rightleftharpoons E_2:\psi ,\] where \( E_i \) is the total space of the stable tangent bundle of \( M_i \), take the Whitney sum with the stable normal bundles of each \( M_i \), so as to get a fiber homotopy equivalence \[ \phi^{\prime}: M_1 \times\mathbb R^k \rightleftharpoons M_2 \times\mathbb R^k :\psi^{\prime}.\] Then \( \psi^{\prime} (M_2 \times 0) \) can be homotoped to an embedding in \( M_1 \times\mathbb R^k \) with a trivial normal bundle, and then (into that trivial normal bundle) we can use \( \phi^{\prime} \) restricted to the 0-section to homotope \( M_1 \times 0 \) to an embedding with a trivial normal bundle.

Thus, we have \( M_1 \times\mathbb R^k \) smoothly embedded in \( M_2 \times\mathbb R^k \), which in turn is smoothly embedded in another copy of \( M_1 \times\mathbb R^k \). Using the \( s \)-cobordism theorem applied to the region between a sphere bundle in the small \( M_1 \times\mathbb R^k \) and a large sphere bundle in the larger \( M_1 \times R^k \), we get that the region is a product, and then that the smaller and larger copies of \( M_1 \times\mathbb R^k \) can be taken to be identical. Then, we see \[ M_1 \times a\mathbb B^k \subset M_2\times b\mathbb B^k \subset M_1 \times c\mathbb B^k \] for some \( 0 < a < b < c \). Now a push-pull argument (do the simple case where \( M_i \) is a point and \( k=2 \)) will give an isotopy that stretches \( M_2 \times\mathbb R^k \) out and onto \( M_1\times\mathbb R^k \), finishing the argument.

It is clear that this sort of argument does not work for \( \mathbb B^k \) instead of \( \mathbb R^k \), for one can no longer push difficulties away to infinity. However, if we assume a simple-homotopy equivalence, then the \( s \)-cobordism theorem can be used to get a diffeomorphism \( M_1 \times\mathbb S^k \to M_2 \times\mathbb S^k \) for large enough \( k \).

The s-cobordism theorem

Smale’s \( h \)-cobordism theorem states that if \( W^{n+1} \), for \( n+1 \geq 6 \), is a smooth, simply connected manifold with two closed boundary components \( N_0^n \) and \( N_1^n \), and if \( W \) is homotopically a product, then \( W \) is diffeomorphic to \( N_0 \times I \) or \( N_1 \times I \). (Homotopically a product means that the inclusions \( N_0 \hookrightarrow W \) and \( N_1 \hookrightarrow W \) are homotopy equivalences.)

The \( s \)-cobordism theorem deals with the nonsimply connected case, where one must have simple-homotopy equivalences in the hypothesis to achieve the same conclusion. The proof is attributed to Barden, Mazur and Stallings (Denis Barden in his Cambridge University PhD thesis, Barry in [5], and John Stallings in his Tata PL-topology notes [e19], all independently). The \( h \)- and \( s \)-cobordism theorems are absolutely crucial geometric tools in all the work on classifying higher-dimensional manifolds, whether in the smooth, PL or topological categories.

It is not too hard to sketch the geometric side of the proofs of the \( h \)- and \( s \)-cobordism theorems by using handlebody theory. Start with a Morse function \( h:W \to [0,1] \) with \( h^{-1}(0) = N_0 \) and \( h^{-1}(1) = N_1 \). If there are no critical points of \( h \), then integrating along gradient flowlines gives a diffeomorphism from \( W \) to \( N_0 \times I = N_1 \times I \).

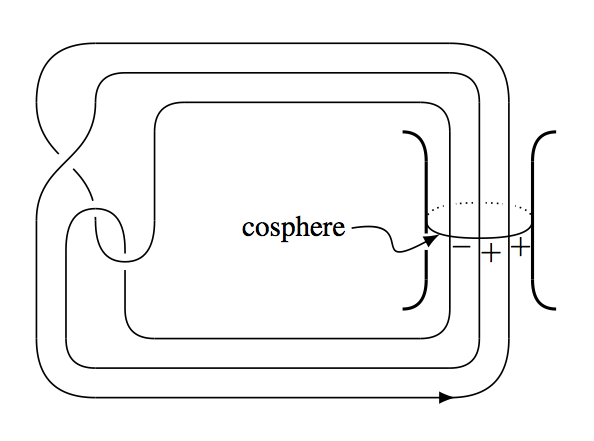

First, note that it is easy to cancel any index-0 or index-\( (n+1) \) critical points, because \( W \) is connected. Now assume \( W \) is simply connected and there are no 1-handles (that is, no critical points of index 1). Because \( H_2(W,N_0;\mathbb Z) = 0 \), there are 3-handles which algebraically cancel the 2-handles, in that a 2-handle has a 3-handle whose attaching 2-sphere intersects the \( (n-2) \)-cosphere of the 2-handle algebraically once. An example of this is seen in the next figure for a 1- and a 2-handle.

Now, we wish to isotope the attaching 2-sphere so that it intersects the \( (n-2) \)-cosphere geometrically once, for then the handles can be canceled. To do this we need the Whitney trick [e2] (see also this exposition) We take a pair of intersection points with opposite sign, and observe that they may be joined by arcs to each of the two spheres, thus forming a loop \( \lambda \) (which is evident in the figure). We need \( \lambda \) to be homotopically trivial, which his true because \( \lambda \) lies in the level set of \( h \) in which the spheres are intersecting, and this level set is the result of attaching 2-handles to the simply connected \( N_0 \), and therefore still simply connected.

Next, we need to smoothly embed the 2-ball \( D \) that is bounded by \( \lambda \) and is mapped into the level set by the homotopy-trivialization of \( \lambda \). This can be done, since \( n \geq 5 \). Now, apply the Whitney trick to isotope the attaching 2-sphere so as to remove the two points of intersection. We iterate this procedure until the spheres intersect in one point, whence the 2-handle and 3-handle can be canceled. We iterate to cancel all the 2-handles, then the 3-handles with 4-handles, and so on — until no handles are left and we are done.

The 1-handles require a special trick, because, after adding 1-handles, the level set is not simply connected. Pick a 1-handle. Its feet can be connected by an arc in \( N_0 \), forming an embedded loop \( \gamma \). This loop \( \gamma \) is homotopically trivial, and thus bounds a disk \( D \) mapped into \( W \). \( D \) can be homotoped so as to be a smoothly embedded disk in a level set just above the 2-handles, with \( \gamma \) moving up if necessary along gradient lines.

At first, \( D \) is not a 2-handle, but we can add a 2–3 canceling pair of handles in which we “blister” \( D \), so that \( D \) is the raised “skin” (a 2-handle) and the 3-handle is the “fluid” in the blister. Then we use this 2-handle to cancel the 1-handle; we have thus traded the 1-handle for a 3-handle. Do this for all 1-handles, and we have finished the proof of the \( h \)-cobordism theorem.

For the \( s \)-cobordism theorem, we need to worry about the Whitney loop not being homotopically trivial. Thus, we need to base each handle in the handlebody decomposition of \( W \), which means we choose a base point \( p \) in \( M_0 \), base points in each handle, and arcs joining these base points to \( p \). The fundamental group \( \pi \) of \( N_0 \) (or \( W \)) now acts on the chain complex \( C_{\ast}(W,N_0) \) by composing an arc with a loop in the fundamental group, which makes the chain complex a module over the group ring \( \mathbb Z[\pi] \). Now a point \( q \) of intersection between the ascending and descending spheres is not only assigned a sign, but also an element of \( \mathbb Z[\pi] \) obtained by running from \( p \) to the ascending sphere, to \( q \), and back down through the descending sphere to \( p \).

Then, when we consider two points of intersection between ascending and descending spheres, they must algebraically cancel over \( \mathbb Z[\pi] \) (instead of being \( +1 \) and \( -1 \), they must be, for example, \( +g \) and \( -g^{-1} \)). In this case, the Whitney loop will be homotopically trivial, and the proof proceeds as in the simply connected case.

In the simply connected case, incidence matrices could always be reduced by row and column moves (handle slides of either the \( k \)-handles or the \( (k+1) \)-handles), but this is not true when \( \pi \) is nontrivial. There is an obstruction in the Whitehead group of \( \pi \), and the simple-homotopy equivalence hypothesis essentially says that this obstruction vanishes. The algebra needed for this discussion is beautifully explained in Milnor’s exposition of Whitehead torsion in [e17].