by Jennifer S. Balakrishnan and Barry Mazur

Overview

- \( A \) is a (polarized) abelian variety defined over \( K \),

- \( C \) is a finite abelian group with a \( G_K \)-action, and

- \( \alpha \) is a \( G_K \)-equivariant injection.

These are the three basic parameters in this general question, and you have your choice of how you want to choose the range of each of them. For example, you can:

- allow the groups \( C \) to run through all cyclic finite groups with arbitrary \( G_K \)-action; and \( A \) to range through all abelian varieties with a specified type of polarization. Equivalently, you are asking about \( K \)-rational cyclic isogenies of abelian varieties, or

- restrict to finite groups \( C \) with trivial \( G_K \)-action, in which case you are asking about \( K \)-rational torsion points on abelian varieties,

- vary over a class of number fields \( K \) — e.g., number fields that are of a fixed degree \( d \) over a given number field \( k \), or

- fix the dimension of the abelian varieties you are considering.

If you organize your parameters appropriately you can “geometrize” your classification problem by recasting it as the problem of finding \( K \)-rational points on a specific algebraic variety.

In more technical vocabulary: you have framed a representable moduli problem — and the algebraic variety in question is called the moduli space representing that moduli problem.

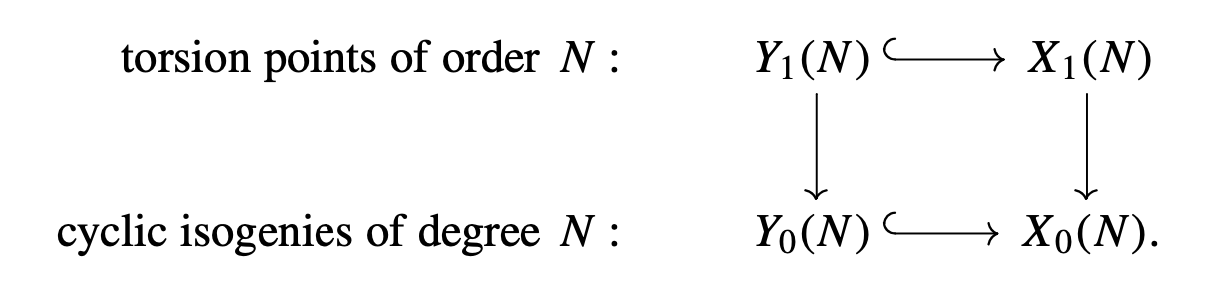

Some classical examples: Modular curves

And, similarly, the classification of elliptic curves defined over \( K \) possessing a \( K \)-rational cyclic isogeny of degree \( N \) is related to the \( K \)-rational points of the affine curve \( Y_0 (N ) \), which is a coarse moduli space. The curve \( X_0 (N ) \) is the smooth projective completion of the curve \( Y_0 (N ) \).

The geometric formulation comes with a number of side-benefits. Here are two:

- If, say, the curve \( X_0 (N ) \) is of genus 0 — noting that one of the cusps \( (\infty \)) is defined over \( \mathbb{Q} \), it follows that there is a rational parametrization of that curve over \( \mathbb{Q} \) which gives us a systematic account (and parametrization); that is, a \( K \)-rational parametrization of cyclic \( N \)-isogenies of elliptic curves — for any \( K \).

- If it is of genus greater than 0, one has a \( \mathbb{Q} \)-rational embedding (sending the cusp \( \infty \) to the origin) \[ X_0 (N ) \hookrightarrow J_0 (N ) \] of the curve in its Jacobian, which allows us to relate questions about \( K \)-rational cyclic \( N \)-isogenies to questions about the Mordell–Weil group (of \( K \)-rational points) of the abelian variety \( J_0 (N ) \).

Besides being able to apply all these resources of Diophantine techniques, there are the simple constructions that are easy to take advantage of.

For example, if you have a moduli space \( \mathcal{M} \) whose \( K \)-rational points for every number field \( K \) provides a classification of your problem over \( K \), then, say, for any prime \( p \) the set of \( K \)-rational points of the algebraic variety that is the \( p \)-th symmetric power of \( \mathcal{M} \) — denoted \( \operatorname{Symm}^p (\mathcal{M}) \) — essentially classifies the same problem ranging over all extensions of \( K \) of degree \( p \). Given a variety \( V \) over a field \( K \), by a degree \( n \) point (of \( V \) over \( K \)) we mean a rational point of \( V \) over some field extension of \( K \) of degree \( n \). The degree 2 points are known as the quadratic points.

As an illustration of this, consider cyclic isogenies of degree \( N \) and noting that the natural \( \mathbb{Q} \)-rational mapping \[ \operatorname{Symm}^p (X_0 (N ))\longrightarrow J_0 (N ) \tag{1.1} \] defined by \[ (x_1 , x_2, \dots, x_p ) \mapsto \text{ Divisor class of }\Bigl[\sum_i x_i - p\cdot \infty\Bigr] \] has linear spaces as fibers, we get that the classification problem of all cyclic \( N \)-isogenies of elliptic curves over all number fields of degree \( p \) is geometrically related, again, to the Mordell–Weil group of \( J_0 (N ) \) over \( \mathbb{Q} \).

A particularly nice example of this strategy carried out in the case of the symmetric square \( \operatorname{Symm}^2 \) of Bring’s curve is in the appendix by Netan Dogra. Bring’s curve is the smooth projective genus 4 curve in \( \mathbb{P}^4 \) defined as the locus of common zeros of the following system of equations: \[ \left\{ \begin{aligned} &x_1^{\phantom{2}} + x_2^{\phantom{2}} + x_3^{\phantom{2}} + x_4^{\phantom{2}} + x_5^{\phantom{2}}= 0,\\ & x^2_1 + x^2_2 + x^2_3 + x^2_4 + x^2_5 = 0,\\ &x^3_1 + x^3_2 + x^3_3 + x^3_4 + x^3_5 = 0. \end{aligned}\right.\tag{1.2} \] It has no real points and thus no rational points. However, there are a number of points defined over \( \mathbb{Q}(i) \), such as \( (1 : i : -1 : -i : 0) \). The natural question is to find all quadratic points on Bring’s curve. Dogra proves that all quadratic points are defined over \( \mathbb{Q}(i) \) and produces the complete list of \( \mathbb{Q}(i) \)-rational points.

Section 2 concentrates on Ogg’s torsion conjectures and the results that have emerged that are relevant to them. In Section 3 we review the broad uniformity conjectures (and results) that have evolved from that work. Section 4 is a discussion of the more recent method of Chabauty, Coleman, and Kim designed to compute rational points on curves by \( p \)-adic considerations; we focus specifically on the results achieved by this method for computation of rational points on specific families of modular curves.

[Editor’s note: The text above is from Section 1 of “Ogg’s torsion conjecture: Fifty years later” published in the Bulletin in April 2025. For the full article, click on the PDF link at the upper right of this page.]