by Robin Thomas

Every planar map of connected countries can be colored using four colors in such a way that countries with a common boundary segment (not just a point) receive different colors. It is amazing that such a simply stated result resisted proof for one and a quarter centuries, and even today it is not yet fully understood. In this article I concentrate on recent developments: equivalent formulations, a new proof, and progress on some generalizations.

Brief history

The Four-Color Problem dates back to 1852 when Francis Guthrie, while trying to color the map of the counties of England, noticed that four colors sufficed. He asked his brother Frederick if it was true that any map can be colored using four colors in such a way that adjacent regions (i.e., those sharing a common boundary segment, not just a point) receive different colors. Frederick Guthrie then communicated the conjecture to DeMorgan. The first printed reference is by Cayley in 1878.

A year later the first “proof” by Kempe appeared; its incorrectness was pointed out by Heawood eleven years later. Another failed proof was published by Tait in 1880; a gap in the argument was pointed out by Petersen in 1891. Both failed proofs did have some value, though. Kempe proved the five-color theorem (Theorem 2 below) and discovered what became known as Kempe chains, and Tait found an equivalent formulation of the Four-Color Theorem in terms of edge 3-coloring, stated here as Theorem 3.

The next major contribution came in 1913 from G. D. Birkhoff, whose work allowed Franklin to prove in 1922 that the Four-Color Conjecture is true for maps with at most 25 regions. The same method was used by other mathematicians to make progress on the Four-Color Problem. Important here is the work by Heesch, who developed the two main ingredients needed for the ultimate proof — “reducibility” and “discharging”. While the concept of reducibility was studied by other researchers as well, the idea of discharging, crucial for the unavoidability part of the proof, is due to Heesch, and he also conjectured that a suitable development of this method would solve the Four-Color Problem. This was confirmed by Appel and Haken (abbreviated A&H) when they published their proof of the Four-Color Theorem in two 1977 papers, the second one joint with Koch. An expanded version of the proof was later reprinted in [1].

Let me state the result precisely. Rather than trying to define maps, countries, and their boundaries, it is easier to restate Guthrie’s 1852 conjecture using planar duality. For each country we select a capital (an arbitrary point inside that country) and join the capitals of every pair of neighboring countries. Thus we arrive at the notion of a plane graph, which is formally defined as follows.

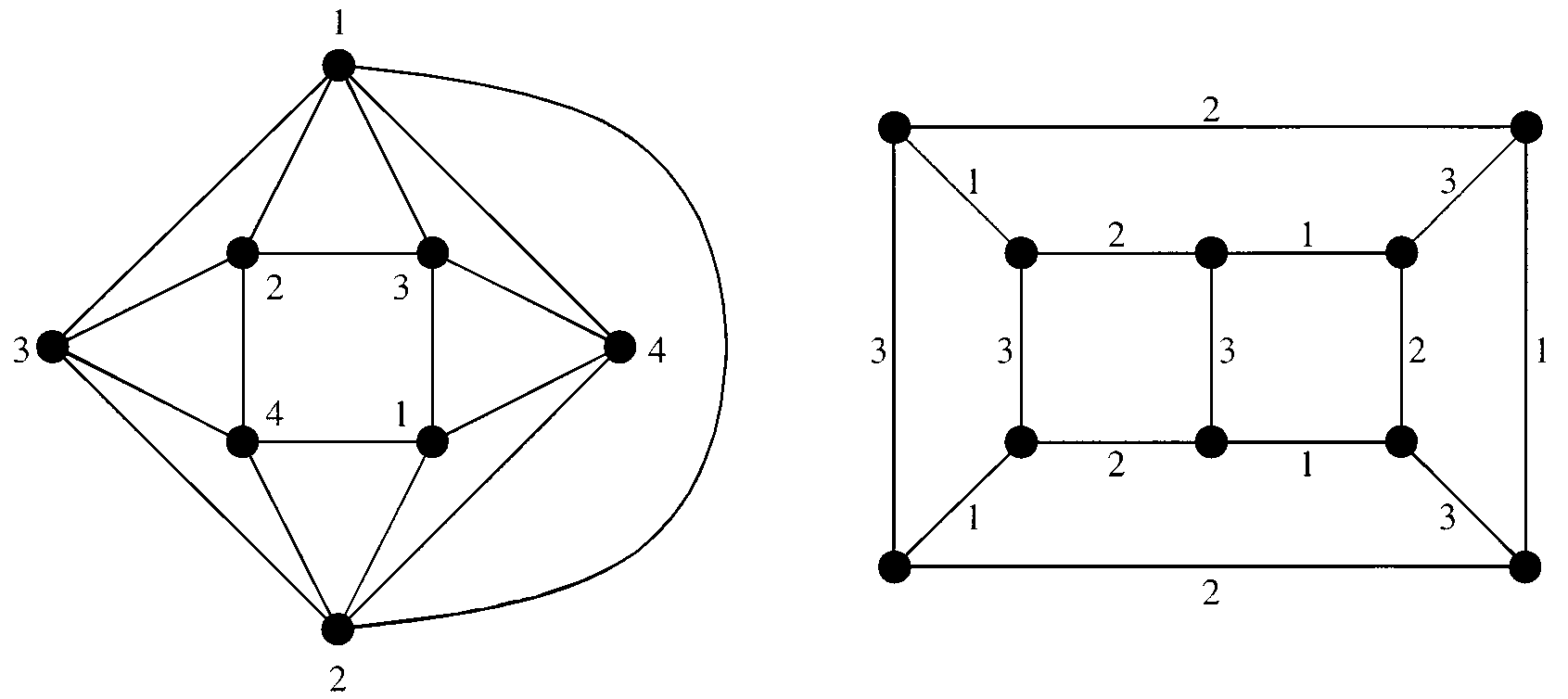

A graph \( G \) consists of a finite set \( V (G) \), the set of vertices of \( G \), a finite set \( E(G) \), the set of edges of \( G \), and an incidence relation between vertices and edges such that every edge is incident with two distinct vertices, called its ends. (Thus I permit parallel edges, but do not allow edges that are loops.) A plane graph is a graph \( G \) such that \( V (G) \) is a subset of the plane, each edge \( e \) of \( G \) with ends \( u \) and \( v \) is a polygonal arc in the plane with end-points \( u \) and \( v \) and otherwise disjoint from \( V (G) \), and every two distinct edges are disjoint except possibly for their ends. A region of \( G \) is an arcwise-connected component of the complement of \( G \). A graph is planar if it is isomorphic to a plane graph. (Equivalently, one can replace “polygonal” in the above definition by “continuous image of \( [0, 1] \)” or, by Fáry’s theorem, by “straight line segment”, and the class of planar graphs remains the same.) For an integer \( k \), a \( k \)-coloring of a graph \( G \) is a mapping \[ \phi : V (G) \to \{1, \dots, k\} \] such that \( \phi(u) = \phi(v) \) for every edge of \( G \) with ends \( u \) and \( v \). An example of a plane graph with a 4-coloring is given in the left half of Figure 1 below. The Four-Color Theorem (abbreviated 4CT) now can be stated as follows.

While Theorem 1 presented a major challenge for several generations of mathematicians, the corresponding statement for five colors is fairly easy to see. Let us state and prove that result now.

Proof. Let \( G \) be a plane graph, and let \( R \) be the number of regions of \( G \). We proceed by induction on \( |V (G)| \). We may assume that \( G \) is connected, has no parallel edges, and has at least three vertices. By Euler’s formula \[ |V (G)| + R = |E(G)| + 2 .\] Since every edge is incident with at most two regions and the boundary of every region has length at least 3, we have \( 2|E(G)| \geq 3R \). Thus \[ |E(G)| \leq 3|V (G)| - 6 .\] The degree of a vertex is the number of edges incident with it. Since the sum of the degrees of all vertices of a graph equals twice the number of edges, we see that \( G \) has a vertex \( v \) of degree at most 5.

If \( v \) has degree at most 4, we consider the graph \( G\backslash v \) obtained from \( G \) by deleting \( v \) (and all edges incident with \( v \)). The graph \( G\backslash v \) has a 5-coloring by the induction hypothesis, and since \( v \) is adjacent to at most four vertices, this 5-coloring may be extended to a 5-coloring of \( G \). Thus we may assume that \( v \) has degree 5. I claim that \( J \), the subgraph of \( G \) induced by the neighbors of \( v \), has two distinct vertices that are not adjacent to each other. Indeed, otherwise \( J \) has \( \bigl(\begin{smallmatrix}5\\2\end{smallmatrix}\bigr) = 10 \) edges, and yet \[ |E(J)| \leq 3|V (J)| - 6 = 9 \] by the inequality of the previous paragraph. Thus there exist two distinct neighbors \( v_1 \) and \( v_2 \) of \( v \) that are not adjacent to each other in \( J \), and hence in \( G \). Let \( H \) be the graph obtained from \( G\backslash v \) by identifying \( v_1 \) and \( v_2 \); it is clear that \( H \) is a graph (it has no loops) and that it may be regarded as a plane graph. By the induction hypothesis the graph \( H \) has a 5-coloring. This 5-coloring gives rise to a 5-coloring \( \phi \) of \( G\backslash v \) such that \( \phi (v_1 ) = \phi (v_2) \). Thus the neighbors of \( v \) are colored using at most four colors, and hence \( \phi \) can be extended to a 5-coloring of \( G \), as desired. □

For future reference it will be useful to sketch another proof of Theorem 2. The initial part proceeds in the same manner until we reach the one and only nontrivial step, namely, when we have a vertex \( v \) of degree 5 and a 5-coloring \( \phi \) of \( G\backslash v \), giving the neighbors of \( v \) distinct colors. Let the neighbors of \( v \) be \( v_1, v_2, \dots, v_5 \), listed in the order in which they appear around \( v \); we may assume that \( \phi (v_i ) = i \). Let \( J_{13} \) be the subgraph of \( G\backslash v \) induced by vertices \( u \) with \( \phi (u) \in \{1, 3\} \). Let \( \phi^{\prime} \) be the 5-coloring of \( G\backslash v \) obtained from \( \phi \) by swapping the colors 1 and 3 on the component of \( J_{13} \) containing \( v_1 \). If \( v_3 \) does not belong to this component, then \( \phi^{\prime} \) can be extended to a coloring of \( G \) by setting \( \phi^{\prime} (v) = 1 \). We may therefore assume that \( v_3 \) belongs to said component and hence there exists a path \( P_{13} \) in \( G\backslash v \) with ends \( v_1 \) and \( v_3 \) such that \( \phi (u) \in \{1, 3\} \) for every vertex \( u \) of \( P_{13} \). Now let \( J_{24} \) be defined analogously, and by arguing in the same manner we conclude that we may assume that there exists a path \( P_{24} \) in \( G\backslash v \) with ends \( v_2 \) and \( v_4 \) such that \( \phi(u) \in \{2, 4\} \) for every vertex \( u \) of \( P_{24} \). Thus \( P_{13} \) and \( P_{24} \) are vertex-disjoint, contrary to the Jordan curve theorem.

Equivalent formulations

Another attractive feature of the 4CT, apart from the simplicity of its formulation, is that it has many equivalent formulations using the languages of several different branches of mathematics. Indeed, in a 1993 article Kauffman and Saleur write: “While it has sometimes been said that the four-color problem is an isolated problem in mathematics, we have found that just the opposite is the case. The four-color problem and the generalization discussed here is central to the intersection of algebra, topology, and statistical mechanics.”

Saaty [e1] presents 29 equivalent formulations of the 4CT. In this article let me repeat the most classical reformulation and then mention three new ones. A graph is cubic if every vertex has degree 3, that is, is incident with precisely three edges. An edge 3-coloring of a graph \( G \) is a mapping \[ \psi : E(G) \to \{1, 2, 3\} \] such that \( \psi (e) \neq \psi (f ) \) for every two edges \( e \) and \( f \) of \( G \) that have a common end. Examples of a cubic graph and an edge 3-coloring are given in the right half of Figure 1. A cut-edge of a graph \( G \) is an edge \( e \) such that the graph \( G\backslash e \) obtained from \( G \) by deleting \( e \) has more connected components than \( G \). It is easy to see that if a cubic graph has an edge 3-coloring, then it has no cut-edge. Tait (see also [e2], or [e5]) showed in 1880 that the 4CT is equivalent to the following.

In this article let me repeat the most classical reformulation and then mention three new ones. A graph is cubic if every vertex has degree 3, that is, is incident with precisely three edges. An edge 3-coloring of a graph \( G \) is a mapping \[ \psi : E(G) \to \{1, 2, 3\} \] such that \( \psi (e) =\psi (f ) \) for every two edges \( e \) and \( f \) of \( G \) that have a common end. Examples of a cubic graph and an edge 3-coloring are given in the right half of Figure 1. A cut-edge of a graph \( G \) is an edge \( e \) such that the graph \( G\backslash e \) obtained from \( G \) by deleting \( e \) has more connected components than \( G \). It is easy to see that if a cubic graph has an edge 3-coloring, then it has no cut-edge. Tait (see also [e2] or [e5]) showed in 1880 that the 4CT is equivalent to the following.

The equivalence of Theorems 1 and 3 is not hard to see and can be found in most texts on graph theory. To illustrate where the equivalence comes from, let us see that Theorem 1 implies Theorem 3. Let \( G \) be a cubic plane graph with no cut-edge; we may assume that \( G \) is connected. The 4CT implies that the regions of \( G \) can be colored using four colors in such a way that the two regions incident with the same edge receive different colors (those two regions are distinct, because \( G \) has no cut-edge). Let us use the colors \( (0, 0) \), \( (1, 0) \), \( (0, 1) \), and \( (1, 1) \) instead of \( 1, 2, 3, 4 \). Given such a 4-coloring, give an edge of \( G \) the color that is the sum of the colors of the two regions incident with it, the sum taken in \( \mathbb{Z}_2\times \mathbb{Z}_2 \). Since the two regions incident with an edge are distinct, only the colors \( (1, 0) \), \( (0, 1) \), and \( (1, 1) \) will be used to color the edges of \( G \), giving rise to an edge 3-coloring of \( G \), as desired.

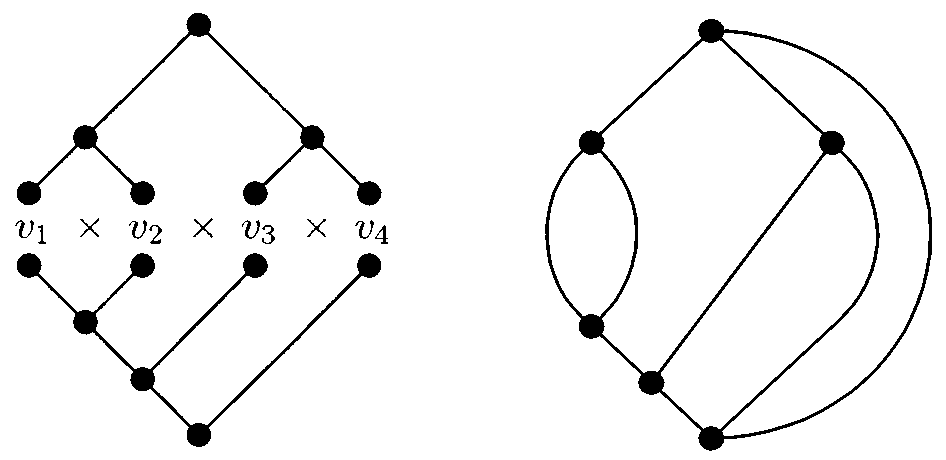

Let me now describe three striking reformulations of the 4CT. The first is similar but deeper than a result found by Whitney and discussed in [e1]. Let \( \times \) denote the vector cross product in \( \mathbb{R}^3 \). The vector cross product is not associative, and hence the expression \[ v_1 \times v_2 \times \cdots \times v_k \] is not well defined, unless \( k \leq 2 \). In order to make the expression well defined, one needs to insert parentheses to indicate the order of evaluation. By an association we mean an expression obtained by inserting \( k - 2 \) pairs of parentheses so that the order of evaluation is determined. Thus \[ (v_1 \times v_2 ) \times (v_3 \times v_4 ) \quad \text{and} \quad ((v_1 \times v_2 ) \times v_3 ) \times v_4 \] are two examples of associations. One can ask whether given two associations of \[ v_1 \times v_2 \times \cdots \times v_k \] there exists some choice of vectors such that the evaluations of the two associations are equal. This is easy to do by choosing \( v_1 = v_2 = \cdots = v_k \). But how about making the two evaluations equal and nonzero? Kauffman [e3] has shown the following.

At this point interested readers might try to prove Theorem 4 before reading further. After all, it is only a statement about the vector cross product in a 3-dimensional space, and so it cannot be too hard. Or can it? Kauffman [e3] has also shown:

Let me clarify that Kauffman proves Theorem 4 by reducing it to the Four-Color Theorem, and so despite Theorem 5 he did not obtain a new proof of the 4CT.

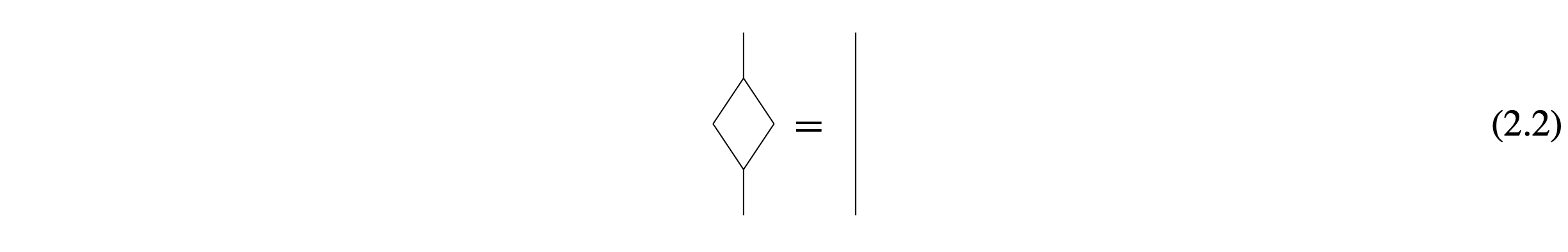

Where does Theorem 5 come from? To understand it, we should think of an association as a rooted tree in the natural sense. Given two associations \( A_1 \) and \( A_2 \) of \[ v_1 \times v_2 \times \cdots\times v_k ,\] let us grow the corresponding trees \( T_1 \) and \( T_2 \) vertically in opposite directions, as in the left half of Figure 2. Let us join the roots of \( T_1 \) and \( T_2 \) by an edge, identify the leaves corresponding to the same variable, and suppress the resulting vertices of degree 2, forming a cubic plane graph \( H \). This process is illustrated in the right half of Figure 2. It is easy to see that \( H \) has no cut-edge and hence has an edge 3-coloring by the 4CT. Let us use the colors \( \mathbf{i}, \mathbf{j}, \mathbf{k} \) instead of 1, 2, 3. Noticing that each variable \( v_i \) corresponds to an edge of \( H \), we see that this edge 3-coloring gives an assignment of \( \mathbf{i}, \mathbf{j}, \mathbf{k} \) to the variables \( v_1, v_2, \dots, v_k \) and it follows from the construction that for this assignment the absolute values of the evaluations of \( A_1 \) and \( A_2 \) are equal to the color assigned to the edge of \( H \) that joins the roots of \( T_1 \) and \( T_2 \). Thus we have shown that the 4CT gives an assignment such that the corresponding evaluations are nonzero and either they are equal or one equals the negative of the other. It can in fact be shown that the evaluations are indeed equal, but we shall not prove that here.

This explains why the 4CT implies Theorem 4. To prove the converse, one must show that it suffices to prove Theorem 3 for cubic graphs \( H \) that arise in the above manner. That follows from a deep theorem of Whitney on hamiltonian circuits in planar triangulations.

For the next reformulation let \( L \) denote the Lie algebra \( \operatorname{sl}(N) \), that is, the vector space of all real \( N \times N \) matrices with trace zero and with the product \( [A, B] \) defined by \[ [A, B] = AB - BA .\] Let \( \{A_i\} \) be a vector space basis of \( L \). The metric tensor \( t_{ij} \) is defined by \( t_{ij} = \operatorname{tr} (A_i, A_j) \), where \( \operatorname{tr} \) denotes the trace of a matrix. Let \( t^{ij} \) denote the inverse of the metric tensor, and let \( f_{ijk} \) be the structure constants of \( L \), defined by \[ f_{ijk} = \operatorname{tr} (A_i [A_j, A_k ]) .\] Now let \( G \) be a cubic graph, and let us choose, for every vertex \( v \in V (G) \), a cyclic permutation of the edges of \( G \) incident with \( v \). Our objective is to define an invariant \( W_L (G) \). To this end, let us break every edge of \( G \) into two half-edges and label all the half-edges by indices from \( \{1, 2, \dots \), \( \dim L\} \). With each such labeling \( \lambda \) we associate the product \[ \pi(\lambda) = \prod_{v\in V(G)} fv \prod_{e\in E(G)}t^e, \] where \( t^e = t^{ij} \) if the two half-edges of \( e \) have labels \( i \) and \( j \) (notice that \( t^{ij} = t^{ji} \)) and \( f_v = f_{ijk} \) if the three half-edges incident with \( v \) have labels \( i, j, k \) and occur around \( v \) in the cyclic order listed (notice that \( f_{ijk} = f_{jki} = f_{kij} \)). Finally, we define \( W_L (G) \) as the absolute value of the sum of \( \pi (\lambda) \) taken over all labelings \( \lambda \) of the half-edges of \( G \) by elements of \( \{1, 2, \dots \), \( \dim L\} \). It follows that \( W_L (G) \) does not depend on the choice of the cyclic permutations. It can also be shown that \( W_L (G) \) does not depend on the choice of basis, but for our purposes it suffices to stick to one fixed basis. Further, it can be shown that \( W_L (G) \) is a polynomial in \( N \) of degree at most \( k = \frac{1}{2} |V (G)| + 2 \), and so we can define \( W^{\operatorname{top}}_L (G) \) to be the coefficient of \( N^k \) in \( W_L(G) \). The next result, due to Bar-Natan [e8], is best introduced by a quote from his paper: “For us who grew up thinking that all there is to learn about \( \operatorname{sl}(N) \) is already in \( \operatorname{sl}(2) \), this is not a big surprise.”

However, the following theorem of Bar-Natan is surprising, regardless of what one grew up thinking about the relationship of \( \operatorname{sl}(2) \) and \( \operatorname{sl}(N) \).

Like Theorem 4, Theorem 6 is deduced from the Four-Color Theorem, and hence Theorem 7 does not yield a new proof of the 4CT.

There is an easy hint as to why Theorem 7 holds. Penrose has shown that \( W_{\operatorname{sl}(2)} (G) \) is a nonzero constant multiple of the number of edge 3-colorings of \( G \). Bar-Natan has shown that if \( G \) is a connected cubic graph, then \( W^{\operatorname{top}}_{\operatorname{sl}(N)} (G) \) is 0 if \( G \) has a cut-edge and is equal to the number of embeddings of \( G \) in the sphere otherwise. The two results combined with Theorem 3 immediately establish Theorems 6 and 7. The details may be found in [e8].

The last reformulation, in terms of divisibility, is due to Matiyasevich [e9].

In fact, Matiyasevich found the functions \( A_k \), \( B_k \), \( C_k \), and \( D_k \) explicitly, and he conjectures that a more general statement holds.

Let us try to understand where this theorem comes from. Let \( \mathbb{N} \) denote the set of nonnegative integers. For a positive integer \( n \) let \( S_n \) denote the infinite graph with vertex-set \( \mathbb{N} \) in which vertices \( i \) and \( j \) are adjacent if \( |i - j| = 1 \) or \( |i - j| = n \). A discrete map is a pair \( (n, \mu) \), where \( n \in \mathbb{N} \) and \( \mu : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N} \) is a mapping such that \( \mu(i) = 0 \) for all but finitely many \( i \in \mathbb{N} \). A discrete map \( (n, \mu) \) gives rise to a graph as follows. Let \( H^{\prime} \) be the subgraph of \( S_n \) induced by all vertices \( i \) with \( \mu(i) \neq 0 \), and let \( H \) be obtained from \( H^{\prime} \) by contracting all edges with ends \( i, j , \) where \( \mu(i) = \mu (j) \). Then \( H \) is indeed a graph (it is loopless), and \( \mu \) is a coloring of \( H \). We say that two discrete maps \( (n, \mu) \) and \( (n^{\prime}, \mu^{\prime}) \) are equivalent if

- \( n = n^{\prime} \),

- \( \mu(i) = 0 \) if and only if \( \mu^{\prime}(i) = 0 \),

- \( \mu (i) = \mu (i + 1) \) if and only if \( \mu^{\prime}(i) = \mu^{\prime}(i + 1) \), and

- \( \mu (i) = \mu(i + n) \) if and only if \( \mu^{\prime} (i) = \mu^{\prime} (i + n) \).

It is not too difficult to show that every planar graph arises as the planar graph \( H \) above for some discrete map and hence the 4CT is equivalent to

By Theorem 2 we can in the above theorem confine ourselves to discrete maps \( (n, \mu) \) such that \( \mu (i) \in \{0, 1, 2, 3, 4,5\} \) for all \( i \in \mathbb{N} \). Each such function \( \mu \) can be encoded as an integer \[ m =\sum^{\infty}_{i=0} \mu (i)7^i .\] Thus the phrase “for every two integers \( n, m \)” in Theorem 8 plays the role of “for every plane graph”. Similarly, the function \( \lambda \) can be encoded as an integer, but we prefer to encode it using the 20 integers \( c_1, c_2, \dots, c_{20} \) defined for \( i = 0, 1, \dots, 4 \) and \( j = 1, 2, 3, 4 \) by \[ c_{4i+j} =\sum (7^k : \mu(k) = i + 1, \lambda(k) = j). \] Now there are conditions the integers \( c_1, c_2,\dots, c_{20} \) have to satisfy in order to represent a valid discrete map \( (n, \lambda) \) as in Theorem 9, but each such condition can be expressed in the form “7 does not divide \( \bigl(\begin{smallmatrix} A+7^nB\\C+7^n D\end{smallmatrix}\bigr) \)”, where \( A, B, C, D \) are linear functions of \( m, c_1, c_2, \dots, c_{20} \). The reader may find more details in [e9].

An outline

The work of Appel and Haken undoubtedly represents a major breakthrough in mathematics, but, unfortunately, there remains some skepticism regarding the validity of their proof. To illustrate the nature of those concerns, let me quote from a 1986 article by Appel and Haken themselves: “This leaves the reader to face 50 pages containing text and diagrams, 85 pages filled with almost 2500 additional diagrams, and 400 microfiche pages that contain further diagrams and thousands of individual verifications of claims made in the 24 lemmas in the main sections of text. In addition, the reader is told that certain facts have been verified with the use of about 1200 hours of computer time and would be extremely time-consuming to verify by hand. The papers are somewhat intimidating due to their style and length and few mathematicians have read them in any detail.”

A discussion of errors, their correction, and other potential problems may be found in the above article, in [1], and in F. Bernhart’s review of [1]. For the purpose of this survey, let me telescope the difficulties with the A&H proof into two points:

- part of the proof uses a computer and cannot be verified by hand, and

- even the part that is supposedly hand-checkable has not, as far as I know, been independently verified in its entirety.

To my knowledge, the most comprehensive effort to verify the A&H proof was undertaken by Schmidt. According to [1], during the one-year limitation imposed on his master’s thesis Schmidt was able to verify about 40 percent of part I of the A&H proof.

Neil Robertson, Daniel P. Sanders, Paul Seymour, and I tried to verify the Appel–Haken proof, but soon gave up and decided that it would be more profitable to work out our own proof. So we did and came up with the proof that is outlined below. We were not able to eliminate reason (1), but we managed to make progress toward (2).

The basic idea of our proof is the same as Appel and Haken’s. We exhibit a set of 633 “configurations” and prove each of them is “reducible”. This is a technical concept that implies that no configuration with this property can “appear” in a minimal counterexample to the Four-Color Theorem. It can also be used in an algorithm, for if a reducible configuration appears in a sufficiently connected planar graph \( G \), then one can construct in constant time a smaller planar graph \( G^{\prime} \) such that any 4-coloring of \( G^{\prime} \) can be converted to a 4-coloring of \( G \) in linear time.

Birkhoff showed in 1913 that every minimal counterexample to the Four-Color Theorem is an “internally 6-connected” triangulation. In the second part of the proof we prove that at least one of our 633 configurations appears in every internally 6-connected planar triangulation (not necessarily a minimal counterexample to the 4CT). This is called proving unavoidability and uses the “discharging method” first suggested by Heesch. Here our method differs from that of Appel and Haken.

The main aspects of our proof are as follows. We confirm a conjecture of Heesch that in proving unavoidability a reducible configuration can be found in the second neighborhood of an “over-charged” vertex; this is how we avoid “immersion” problems that were a major source of complication for Appel and Haken. Our unavoidable set has size 633 as opposed to the 1,476-member set of Appel and Haken; our discharging method uses only 32 discharging rules instead of the 487 of Appel and Haken; and we obtain a quadratic algorithm to 4-color planar graphs, an improvement over the quartic algorithm of Appel and Haken. Our proof, including the computer part, has been independently verified, and the ideas have been and are being used to prove more general results. Finally, the main steps of our proof are easier to present, as I will attempt to demonstrate below.

Before I turn to a more detailed discussion of configurations, reducibility, and discharging, let me say a few words about the use of computers in our proof. The theoretical part is completely described in [e6], but it relies on two results that are stated as having been proven by a computer. The rest of [e6] consists of traditional (computer-free) mathematical arguments. There is nothing extraordinary about the theoretical arguments, and so the main burden of verification lies in those two computer proofs. How is one supposed to be convinced of their validity? There are basically two ways. The reader can either write his or her own computer programs to check those results (they are easily seen to be finite problems), or he or she can download our programs along with their supporting documentation and verify that those programs do what we claim they do.

The reducibility part is easier to believe, because we are doing almost the same thing as many authors before us (including Appel and Haken) have done, and so it is possible to compare certain numerical invariants obtained during the computation to gain faith in the results. This is not possible in the unavoidability part, because our approach to it is new. To facilitate checking, we have written this part of the computer proof in a formal language so that it will be machine verifiable. Every line of the proof can be read and checked by a human, and so can (at least theoretically) the whole argument. However, the entire argument occupies about 13,000 lines, and each line takes some thought to verify. Therefore, verifying all of this without a computer would require an amount of persistence and determination my coauthors and I do not possess. The computer data, programs, and documentation are available by anonymous ftp1 and can also be conveniently accessed on the World Wide Web.2

Two of my students independently verified the computer work. Tom Fowler verified the reducibility part (and in fact extended it to obtain a more general result — see later), and Christopher Carl Heckman wrote an independent version of the unavoidability part using a different programming language. Bojan Mohar also informed us that his student Gašper Fijavž wrote independent programs and was able to confirm both parts of the computer proof. The computer verification can be carried out in a matter of several hours on standard commercially available equipment.

I should mention that both our programs use only integer arithmetic, and so we need not be concerned with round-off errors and similar dangers of floating point arithmetic. However, an argument can be made that our “proof” is not a proof in the traditional sense, because it contains steps that most likely can never be verified by humans. In particular, we have not proven the correctness of the compiler on which we compiled our programs, nor have we proven the infallibility of the hardware on which we ran our programs. These have to be taken on faith and are conceivably a source of error. However, from a practical point of view, the chance of a computer error that appears consistently in exactly the same way on all runs of our programs on all the compilers under all the operating systems that our programs run on is infinitesimally small compared to the likelihood of a human error during the same amount of case-checking. Apart from this hypothetical possibility of a computer consistently giving an incorrect answer, the rest of our proof, including the programs, can be checked in the same way as traditional mathematical proofs. My coauthors and I concede, however, that checking a computer program is much more difficult than verifying a mathematical proof of the same length.

Configurations

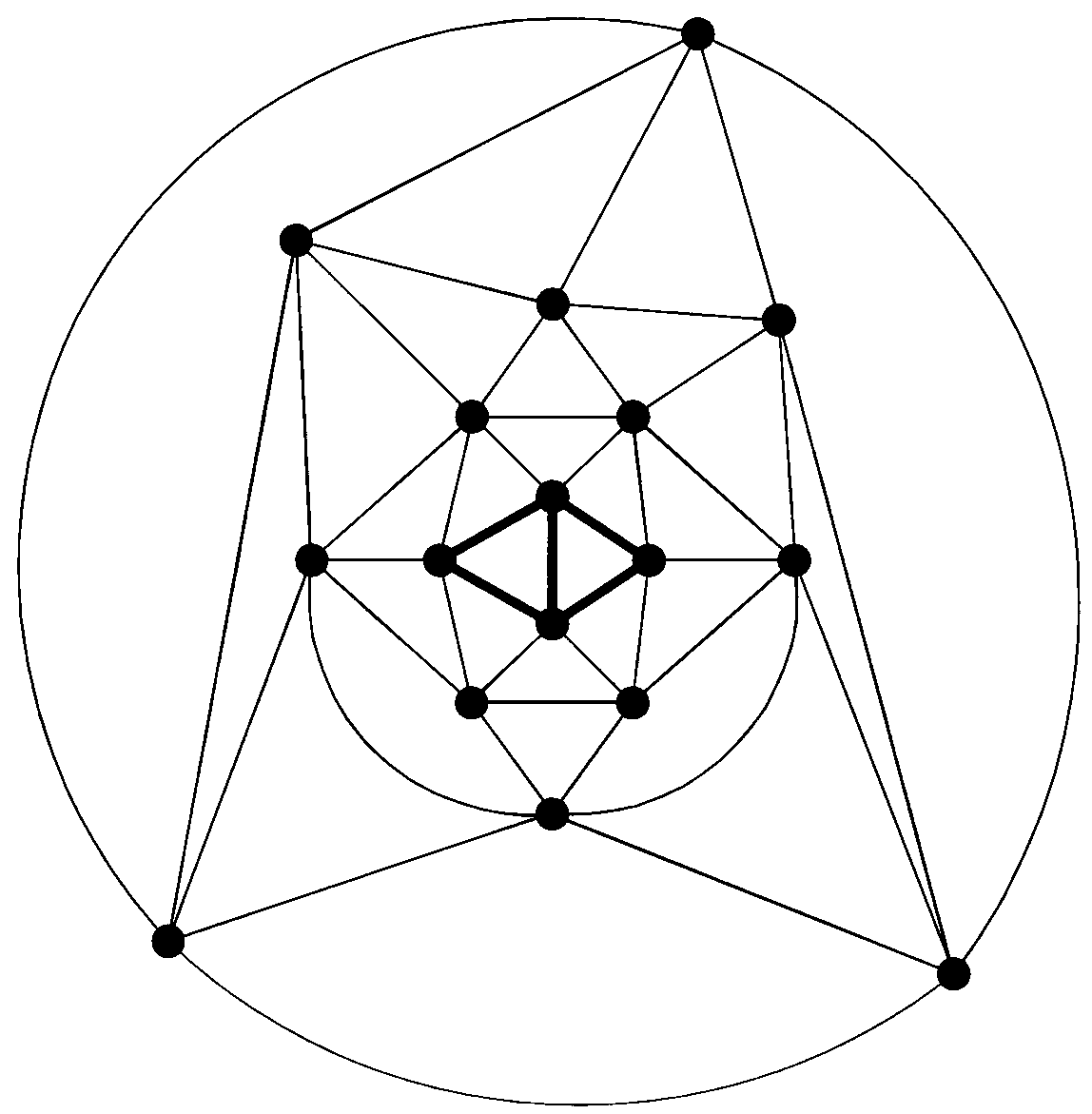

First we need a result of Birkhoff about connectivity of minimal counterexamples. Let \( G \) be a plane graph. A triangle is a region of \( G \) bounded by precisely three edges of \( G \). A plane graph \( G \) is a triangulation if every region of \( G \) (including the unbounded region) is a triangle. See Figure 3 for an example. A graph \( G \) is internally 6-connected if for every set \( X \) of at most five vertices, either the graph \( G\backslash X \) obtained from \( G \) by deleting \( X \) is connected, or \( |X| = 5 \) and \( G\backslash X \) has exactly two connected components, one of which consists of a single vertex. Thus every vertex of an internally 6-connected graph has degree at least 5. For example, the triangulation in Figure 3 is internally 6-connected. Let me formally state the result of Birkhoff mentioned earlier. A proof can be obtained by pushing the arguments presented in the two proofs of Theorem 2.

Next we need to introduce the concept of a configuration, which is central to the rest of the proof. Configurations are technical devices that permit us to capture the structure of a small part of a larger triangulation. A graph \( G \) is an induced subgraph of a graph \( T \) if \( G \) is a subgraph of \( T \) and every edge of \( T \) with both ends in \( V (G) \) belongs to \( G \). If \( (G, \gamma) \) is a configuration, one should think of \( G \) as an induced subgraph of an internally 6-connected triangulation \( T \), with \( \gamma(v) \) being the degree of \( v \) in \( T \). This notion can be traced back to Birkhoff’s 1913 paper and has been used in various forms by many researchers since then. Here is the formal definition of the version that we use.

A near-triangulation is a nonnull connected plane graph with one region designated as special such that every region, except possibly the special region, is a triangle. A configuration \( K \) is a pair \( (G, \gamma) \), where \( G \) is a near-triangulation and \( \gamma \) is a mapping from \( V(G) \) to the integers with the following properties:

- for every vertex \( v \) of \( G \), if \( v \) is not incident with the special region of \( G \), then \( \gamma(v) \) equals \( \deg(v) \), the degree of \( v \), and otherwise \( \gamma(v) > \deg(v) \), and in either case \( \gamma(v) \geq 5 \);

- for every vertex \( v \) of \( G \), \( G\backslash v \) has at most two components, and if there are two, then the degree of \( v \) in \( G \) is \( \gamma (v) - 2 \);

- \( K \) has ring-size at least 2, where the ring-size of \( K \) is defined to be \[ \sum(\gamma(v) - \deg(v) - 1) ,\] summed over all vertices \( v \) incident with the special region of \( G \) such that \( G\backslash v \) is connected.

The significance of condition (1) will become clearer from the definition of “appears” below; conditions (2) and (3) are needed for the definition of the “free completion”, discussed in the next section.

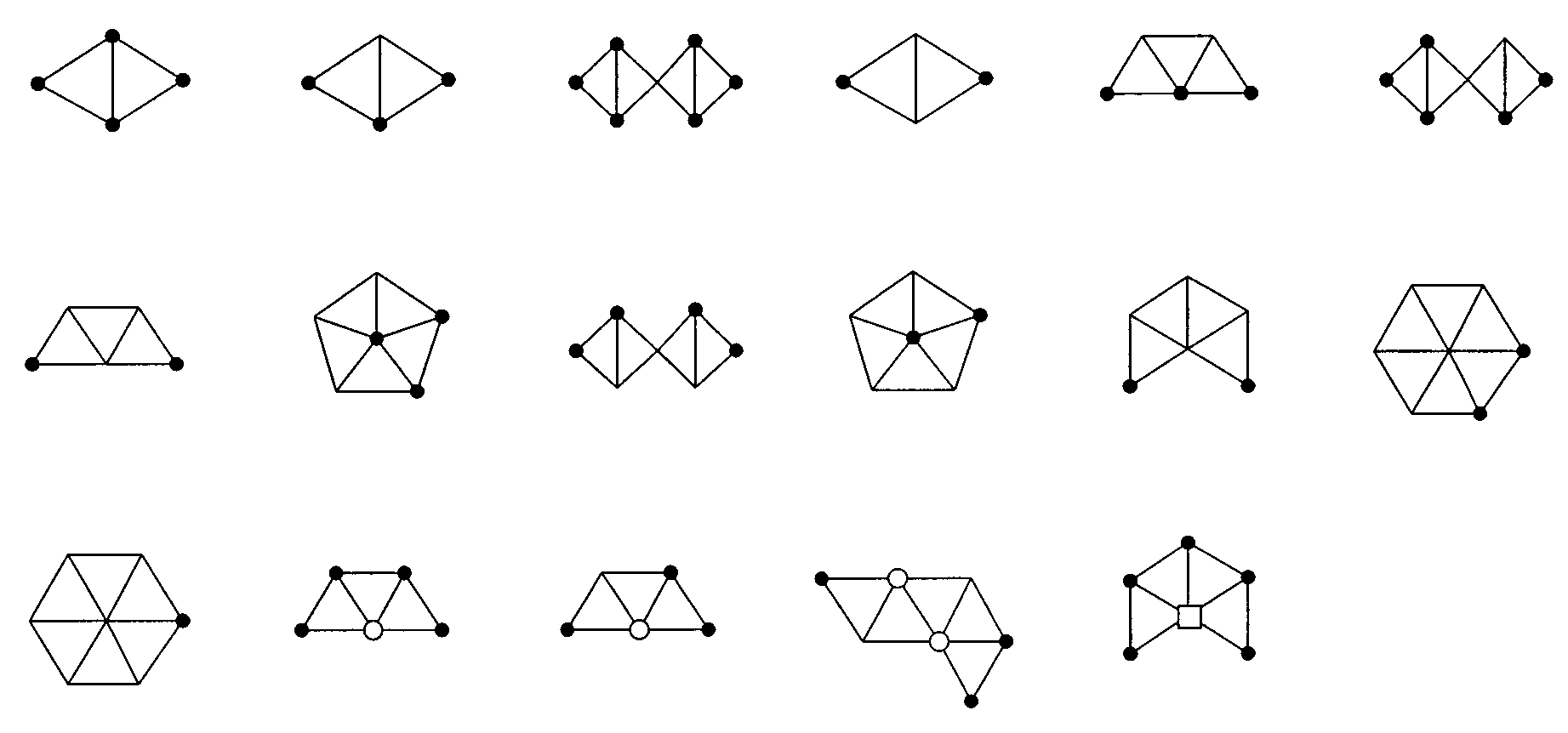

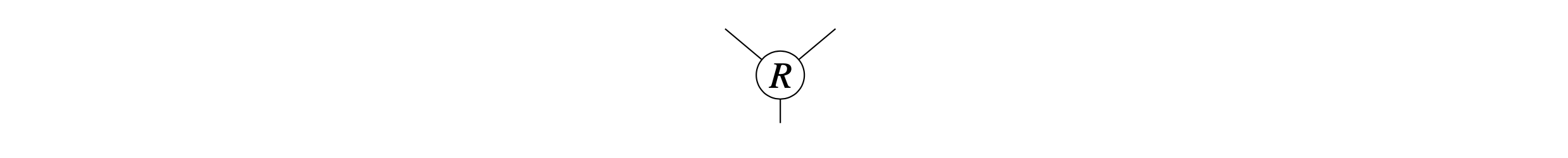

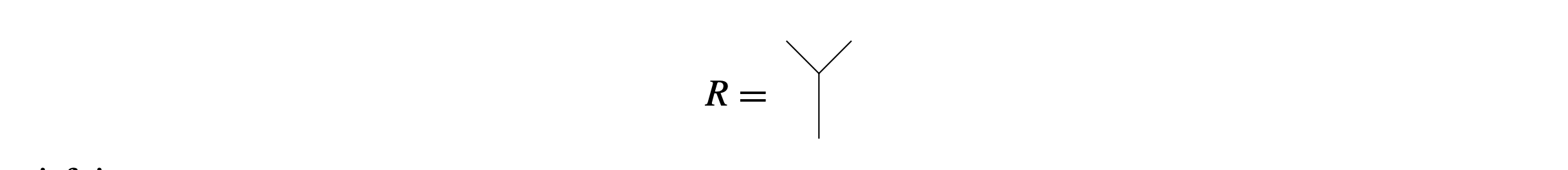

When drawing pictures of configurations, one possibility is to draw the underlying graph and write the value of \( \gamma \) next to each vertex. There is a more convenient way, introduced by Heesch. The special region is the unbounded region, and the shapes of vertices indicate the value of \( \gamma(v) \) as follows: A solid black circle means \( \gamma(v) = 5 \), a dot (or what appears in the picture as no symbol at all) means \( \gamma(v) = 6 \), a hollow circle means \( \gamma(v) = 7 \), a hollow square means \( \gamma(v) = 8 \), a triangle means \( \gamma(v) = 9 \), and a pentagon means \( \gamma(v) = 10 \). In Figure 4, 17 of our 633 reducible configurations are displayed using the indicated convention. The whole set can be found in [e6] and can be viewed electronically.3

Isomorphism of configurations is defined in the natural way. Any configuration isomorphic to one of the 633 configurations exhibited in [e6] is called a good configuration. Let \( T \) be a triangulation. A configuration \( (G, \gamma) \) appears in \( T \) if \( G \) is an induced subgraph of \( T \), every region of \( G \) except possibly the special region is a region of \( T \), and \( \gamma(v) \) equals the degree of \( v \) in \( T \) for every vertex \( v \) of \( G \). See Figure 3 for an example of a configuration isomorphic to the first configuration in Figure 4 appearing in an internally 6-connected triangulation. We prove the following two statements.

For example, the good configuration in the upper left corner of Figure 4 appears in the center of Figure 3.

From Theorems 10, 11, and 12 it follows that no minimal counterexample exists, and so the 4CT is true. I will discuss the proofs of the latter two theorems in the next two sections.

Reducibility

Reducibility is a technique for proving statements such as Theorem 11. Qualitatively it can be described by saying that it is obtained by pushing to the limit the arguments used in the two proofs of Theorem 2. It was developed from Kempe’s failed attempt at proving the 4CT by Birkhoff, Bernhart, Heesch, Allaire, Swart, Appel and Haken, and others.

I will explain the idea of reducibility by giving an example; interested readers may find the precise definition in [e6]. Let us consider the first configuration in Figure 4, and let us call it \( K = (G, \gamma) \). Suppose for a contradiction that \( K \) appears in a minimal counterexample \( T \) to the 4CT. Given that \( \gamma(v) \) is equal to the degree in \( T \) of the vertex \( v \) of \( G \), we can deduce what \( T \) looks like in a small “neighborhood” of \( G \). In fact, since \( T \) is internally 6-connected by Theorem 10, it follows that the graph \( S \) pictured in Figure 5 is isomorphic to a subgraph of \( T \), and so we may assume that \( S \) is actually a subgraph of \( T \). Notice that \( G \) is a subgraph of \( S \), that \( R = S\backslash V (G) \) is a (simple) circuit with vertex-set \( \{v_1, v_2, \dots \), \( v_6\} \), and that the length of \( R \) is equal to the ring-size of \( K \). We call \( S \) the free completion of \( K \).

(Here we were lucky — for larger configurations it does not follow that the free completion is a subgraph of \( T \). However, the most that can happen, given that \( G \) is an induced subgraph of \( T \), is that for some distinct vertices of \( R \) the corresponding vertices of \( T \) are equal. On the other hand, this does not matter for the forthcoming argument, and so for the purpose of this article let me ignore this possibility.)

Now let us consider \[ T^{\prime} = T \backslash V (G) .\] Let \( \mathcal{K} \) be the set of all 4-colorings of \( R \), and let \( \mathcal{C}^{\prime}\subseteq \mathcal{K} \) be the set of all those 4-colorings of \( R \) that extend to a 4-coloring of \( T^{\prime} \). Since \( T \) is a minimal counterexample, \( T^{\prime} \) has a 4-coloring, and hence \( \mathcal{C}^{\prime} = \emptyset \). To obtain a contradiction, let me prove that \( \mathcal{C}^{\prime} = \emptyset \). Let \( \mathcal{C} \) be the set of all 4-colorings of \( R \) that extend to a 4-coloring of \( S \). Notice that \( \mathcal{C} \) can be computed from the knowledge of the configuration \( K \). Since \( T \) is a counterexample to the 4CT, \( \mathcal{C}^{\prime} \subseteq \mathcal{K} - \mathcal{C} \) (otherwise a 4 -coloring of \( R \) that extends to both \( S \) and \( T^{\prime} \) extends to a 4-coloring of \( T \)). We need a method that would allow us to show that a 4-coloring \( \phi \in \mathcal{K} - \mathcal{C} \) does not belong to \( \mathcal{C}^{\prime} \). As an example let us consider the 4-coloring \( \phi \) of \( R \) defined by \[ (\phi(v_1 ), \phi(v_2 ), \dots, \phi(v_6)) = (1, 2, 1, 3, 1, 2) ,\] where \( v_1, v_2, \dots, v_6 \) are the vertices of \( R \), numbered as in Figure 5. To simplify the notation, I shall write \( \phi = 121312 \) and similarly for other colorings. Suppose for a contradiction that \( \phi \in \mathcal{C}^{\prime} \), and let \( \kappa \) be a 4-coloring of \( T^{\prime} \) extending \( \phi \). Let \( T_{14} \) be the subgraph of \( T^{\prime} \) induced by the vertices \( v \in V (T^{\prime}) \) with \( \kappa(v) \in \{1, 4\} \), and let \( L \) be the component of \( T_{14} \) containing the vertex \( v_1 \). Let \( \kappa^{\prime} \) be obtained from \( \kappa \) by exchanging colors 1 and 4 on vertices of \( L \), and let \( \phi^{\prime} \) be the restriction of \( \kappa^{\prime} \) to \( R \). Thus \( \phi^{\prime} \in \mathcal{C}^{\prime} \). If \( v_3 , v_5 \notin V (L) \), then \( \phi^{\prime} = 421312 \), and if \( v_3 \notin V (L) \), \( v_5 \in V (L) \), then \( \phi^{\prime} = 421342 \). In either case \( \phi^{\prime} \in \mathcal{C} \) (see Figure 6), a contradiction. Thus \( v_3 \in V (L) \), and hence there exists a path \( P \) in \( T^{\prime} \) with ends \( v_1 \) and \( v_3 \) such that \( \kappa(v) \in \{1, 4\} \) for every \( v \in V (P ) \). Let \( T_{23} \) be defined analogously, and let \( J \) be the component of \( T_{23} \) containing \( v_2 \). Since \( V (J) \cup V (P ) = \emptyset \) we deduce from the Jordan curve theorem that \( v_4, v_6 \notin V (J) \). Let \( \kappa^{\prime\prime} \) be obtained from \( \kappa \) by exchanging colors 2 and 3 on vertices of \( J \), and let \( \phi^{\prime\prime} \) be the restriction of \( \kappa^{\prime\prime} \) to \( R \). Then \( \phi^{\prime\prime} = 131312 \), and hence \( \phi^{\prime\prime} \in \mathcal{C} \) (see Figure 6), and yet \( \phi^{\prime\prime} \in \mathcal{C}^{\prime} \), a contradiction. Thus \( \phi \notin \mathcal{C}^{\prime} \), as required. The arguments for other colorings in \( \mathcal{K} - \mathcal{C} \) proceed similarly. The order in which colorings are handled is important here, because for some colorings it is necessary to use the previously established fact that other colorings in \( \mathcal{K} - \mathcal{C} \) do not belong to \( \mathcal{C}^{\prime} \).

The above argument is called D-reducibility in the literature. Notice the way in which we used the fact that \( T \) is a minimal counterexample — we used it to deduce that \( T^{\prime} \) has a 4-coloring. This may seem wasteful, for rather than deleting \( G \), we could replace it by a smaller graph \( G^{\prime} \). Doing so yields a more powerful method, called C-reducibility. In our proof of the 4CT we use a special case of C-reducibility, where \( G^{\prime} \) is obtained from \( G \) by contracting at most four edges. C-reducibility is dangerous in general, because it requires checking that the new graph obtained by substituting \( G^{\prime} \) for \( G \) is loopless, which can be rather tedious. By limiting ourselves to graphs obtained by contracting at most four edges, we were able to eliminate these difficulties.

D- and C-reducibility can be automated and carried out on a computer. In fact, they must be carried out on a computer, because we need to test configurations with ring-size as large as 14, in which case there are almost 200,000 colorings to be checked. At the present time there is little hope of doing this part of the proof by hand. Even writing down the proof in a formal language, as we did for the discharging part, does not seem practical because of the length of the argument.

Discharging

Discharging is a clever and effective use of Euler’s formula, first suggested by Heesch and later used by Appel and Haken and many others since then. In fact, discharging has become a standard tool in graph theory. In what follows I will refer to Figure 7, which some readers may find overwhelming at the first sight. I recommend focusing attention on the first row and thinking of the rest as being of secondary importance. The first row has a geometric interpretation, discussed below. Also, we will make use of Heesch’s notational convention introduced two paragraphs prior to Theorem 11.

Let \( T \) be an internally 6-connected triangulation. Initially, every vertex \( v \) is assigned a charge of \[ 10(6 - \deg(v)) .\] It follows from Euler’s formula that the sum of the charges of all vertices is 120; in particular, it is positive. We now redistribute the charges according to the following rules. Whenever \( T \) has a subgraph isomorphic to one of the graphs in Figure 7 satisfying the degree specifications (for a vertex \( v \) of one of those graphs with a minus sign next to \( v \), this means that the degree of the corresponding vertex of \( T \) is at most the value specified by the shape of \( v \), and analogously for vertices with a plus sign next to them; equality is required for vertices with no sign next to them), a charge of 1 (2 in case of the first graph) is to be sent along the edge marked with an arrow.

This procedure defines a new set of charges with the same total sum. For instance, if \( T \) is the triangulation depicted in Figure 3, then only the rule corresponding to the first graph in Figure 7 applies, and it causes a charge of 2 to be sent along each edge in either direction. Hence the net effect of all the rules is zero, and so every vertex ends up with a final charge of 10.

Since the total sum of the new charges is positive, there is a vertex \( v \) in \( T \) whose new charge is positive. We show that a good configuration appears in the second neighborhood of \( v \) (that is, the subgraph induced by vertices at distance at most 2 from \( v \)). If the degree of \( v \) is at most 6 or at least 12, then this can be seen fairly easily by a direct argument. (See [e6] for details; for this argument the configurations of Figure 4 suffice. In fact, when \( v \) has degree at most 6, this follows immediately from the geometric interpretation of the first row of Figure 7 given at the end of this section.) For the remaining cases, however, the proofs are much more complicated. Since the amount of charge a vertex of \( T \) receives depends only on its second neighborhood (and not on the rest of \( T \)), it suffices to examine all possible second neighborhoods of vertices of degree 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11. It is easy to see that this reduces to a finite problem. Strictly speaking, there are infinitely many such second neighborhoods, but for vertices of degree at least 12 the actual degree affects neither the amount of charge nor the presence of reducible configurations. Thus all possible second neighborhoods can be divided into finitely many classes, where for every two second neighborhoods in the same class, the same good configurations appear and the central vertex has the same charge. Therefore, it suffices to examine all these equivalence classes. As mentioned earlier, this part of the proof has actually been written down in a formal language.

The rules corresponding to the first row in Figure 7 were derived from an elegant method of Mayer and have the following geometric interpretation. Let \( v \in V (T ) \) have degree 5, and assume, as we may in the proof of Theorem 12, that no good configuration appears in the second neighborhood of \( v \). The vertex \( v \) is originally assigned a charge of 10. The rules in the first row are designed to send this charge from \( v \) to vertices of degree at least 7. Let \( e \) be an edge incident with \( v \), let \( u \) be the other end of \( e \), and let \( x \) be a common neighbor of \( u \) and \( v \). Since \( T \) is internally 6-connected, there are exactly ten such pairs \( (e, x) \). For each such pair a charge of 1 will be sent away from \( v \) into a suitable vertex, found as follows. If the degree of \( u \) is at least 7, the unit of charge will be deposited into \( u \). Otherwise, if \( x \) has degree at least 7, the unit of charge will be deposited into \( x \). Finally, if both \( u \) and \( x \) have degree at most 6, let \[ z_1 = v, \,z_2 = u, \,z_3, \,z_4, \dots \] be the neighbors of \( x \) listed in the order in which they appear around \( x \). Since no good configuration appears in the second neighborhood of \( v \), one of these vertices has degree at least 7, as is easily seen. Thus we may take the smallest integer \( i \geq 2 \) such that \( z_i \) has degree at least 7, and the unit of charge corresponding to \( (e, x) \) will be deposited into \( z_i \).

While this redistribution of charges seems natural, unfortunately it is not true that a reducible configuration appears in the second neighborhood of every vertex of positive charge. Therefore, we had to introduce additional rules to make small changes to this distribution to take care of second neighborhoods of vertices with positive charge in which no reducible configuration appeared. The additional rules were obtained by trial and error; there is a lot of flexibility in their choice, but they were not designed with any geometric intuition behind them.

Beyond the Four-Color Theorem

The new proof of the 4CT gives hope that other more general conjectures that are known to imply the 4CT could be settled by an appropriate adaptation of the same methods. Let me start by discussing a result of my student Tom Fowler on unique colorability. A graph \( G \) is uniquely 4-colorable if it has a 4-coloring and every two 4-colorings differ only by a permutation of colors. Here is a construction. Start with the complete graph on four vertices. Given a plane graph \( G \) constructed thus far, pick a triangle in \( G \), and add a new vertex adjacent to all vertices incident with the triangle. It is easy to see that every graph constructed in this fashion is uniquely 4-colorable. Fiorini and Wilson conjectured in 1977 that every uniquely 4-colorable plane graph on at least four vertices can be obtained this way. Fowler in his Ph.D. thesis extended our proof of the 4CT to prove this conjecture. More precisely, he has shown

By Theorem 10 this generalizes the Four-Color Theorem, and it implies the Fiorini–Wilson conjecture by a result of Goldwasser and Zhang, who have shown that a minimal counterexample is internally 6-connected. (The proof of the latter is analogous to that of Theorem 10.)

While the 4CT becomes false very quickly once we leave the world of planar graphs, Tutte noticed that Theorem 3 remains true for a reasonably large class of nonplanar graphs. The smallest cubic graph with no cut-edge and no edge 3-coloring is the famous Petersen graph depicted in Figure 8. We say that a graph \( G \) has an \( H \) minor if a graph isomorphic to \( H \) can be obtained from a subgraph of \( G \) by contracting edges. Tutte conjectured the following.

Tutte’s conjecture implies the 4CT by Theorem 3 (because the Petersen graph is not planar, and contraction preserves planarity), but it seems to be much stronger. However, it now appears that there is a good chance that Tutte’s conjecture can be proven. Indeed, Robertson, Seymour, and I have reduced the problem to the following two classes of graphs. We say that a graph \( G \) is apex if \( G\backslash v \) is planar for some vertex \( v \) of \( G \), and we say that a graph is doublecross if it can be drawn in the plane with two crossings in such a way that the two crossings belong to the same region (see Figure 9). Robertson, Seymour, and I [e7] have shown the following.

Thus, in order to prove Conjecture 14 it suffices to prove it for apex and doublecross graphs, two classes of graphs that are “almost” planar. In fact, my recent work with Sanders suggests that it might be possible to adapt our proof of the 4CT to show that no apex graph is a counterexample to Tutte’s conjecture. There is an indication that the doublecross case will be easier, but we cannot confirm that yet.

There is a way to generalize the 4CT along the lines of (vertex) 4-coloring. Hadwiger conjectured the following.

This is trivial for \( t \leq 2 \), and for \( t = 3 \) it was shown by Hadwiger and Dirac (this case is also reasonably easy). However, for every \( t \geq 4 \), Hadwiger’s conjecture implies the 4CT. To see this, take a plane graph \( G \), and construct a graph \( H \) by adding \( t - 4 \) vertices adjacent to each other and to every vertex of \( G \). Then \( H \) has no \( K_{t+1} \) minor (because no plane graph has a \( K_5 \) minor) and hence has a \( t \)-coloring by the assumed truth of Hadwiger’s conjecture. In this \( t \)-coloring, vertices of \( G \) are colored using at most four colors, as required. Thus there is a rather sharp increase in the level of difficulty of Hadwiger’s conjecture between \( t = 3 \) and \( t = 4 \). On the other hand, Wagner showed in 1937 that Hadwiger’s conjecture for \( t = 4 \) is in fact equivalent to the 4CT. (Notice that this result preceded the proof of the 4CT by four decades and, in fact, inspired Hadwiger’s conjecture.) Recently, Robertson, Seymour, and I were able to show that the next case is also equivalent to the 4CT [e4]. More precisely, we managed to prove (without using the 4CT) the following.

By the 4CT every apex graph has a 5-coloring, and so Hadwiger’s conjecture for \( t = 5 \) follows. The cases \( t \geq 6 \) are still open.