| [letterhead] | |

| Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences | |

| 251 Mercer Street | [handwriting] February 22, ’87 |

| New York, N.Y. 10012 | |

| Telephone: (212) 460-7100 |

Dear Yves,

How are you? I’ve been meaning to write for a long time, and I’m a bit embarrassed that I’ve waited so long. But here finally are some news.

Ann Arbor has offered us, Robert and me both, associate professorships (“with tenure”). They told me that they were quite impressed by your letter of recommendation, for which I would like to thank you again. Moreover, Bell Laboratories has also made me an offer (Robert is working there already). We have to decide before March 1 (one week to go…) If it were only up to me, I think I’d likely go for Ann Arbor: I like the area very much, and it is a good university. And I would learn a lot of math there. On the other hand, Robert is rather more attached to Bell Labs than I thought (and than he himself thought, in fact), and, since I don’t want to start our marriage by taking him away from Bell when he likes it there, we will probably opt for the Bell alternative. Actually I think I’ll enjoy Bell too, quite a bit: there are very good mathematicians there too, and they give their researchers a lot of freedom. You’d said that, if we went to Ann Arbor, you’d come visit us — Robert and me and the kids. I hope you will come see us even if we cast our lot with Bell! I think you will find interesting certain of the mathematicians (Andrew Odlyzko, Ron Graham, Larry Shepp, Jeff Lagarias, Neil Sloane,…). They too were very impressed by your recommendation. Thanks for opening those doors to me!

While waiting to decide with final certainty (which will happen this week), I have finally finished the big paper on frames (which I was really fed up with by the end), and returned to wavelets. The arrival of Stéphane Mallat’s paper, which I thought very beautiful, led me to mulling on orthonormal wavelet bases. I wondered, too, whether a “pyramid” algorithm such as the one in Mallat’s paper must necessarily be founded on a wavelet basis. I discussed this with the “vision” people here, and they seem to think that an orthogonality property for subspaces of \( \ell^2(\mathbb{Z}) \), which then requires the existence of an orthonormal wavelet basis underlying the “pyramid”, is essential. This whole thing has led me also to the construction of orthonormal bases of wavelets with compact support. (Here am I, who had always worked with frames, surrendering to orthonormality too!) Such bases exist, but the ones I’ve found look a bit strange.

The idea is the following.

Let’s try to construct sequences \( f(n), g(n) \) such that \begin{equation} \tag{1} \sum_k f(n-2k)f^*(\ell-2k) + g(n-2k)g^*(\ell-2k)=\delta_{n\ell}. \end{equation} (In essence, that’s all that’s needed for an \( \ell^2(\mathbb{Z}) \) decomposition-and-reconstruction “pyramid” to work.)

We can then define \( G,F:\ell^2(\mathbb{Z})\to\ell^2(\mathbb{Z}) \) by \[ (Fc)_k=\sum_n f(n-2k)c_n, \quad (Gc)_k=\sum_n g(n-2k)c_n. \] Then \( F^*F+G^*G=\unicode{x1D7D9} \), and we have \[ (F^*)^N F^N+\sum^N_{j=1} F^{*N-j}G^*G F^{N-j} = \unicode{x1D7D9}, \] that is, a decomposition-and-reconstruction of \( \ell^2(\mathbb{Z}) \) with a pyramid algorithm. In practice, we will choose \( f,g \) to be real.

It seems reasonable (but not necessary) to limit ourselves to the case where \[ F^*\ell^2(\mathbb{Z})\perp G^*\ell^2(\mathbb{Z}) \] (it is clear that the sum of the two spaces is \( \ell^2 \) in all cases). This would lead (according to the intuition of the vision people) to a greater degree of data compaction than the non-orthogonal case. So we impose the condition \begin{equation} \tag{2} \sum_n f(n-2k)\,g^*(n-2\ell)=0. \end{equation} Clearly all the conditions are satisfied if the \( f,g \) are obtained starting from a wavelet basis. On the other hand, if \begin{equation} \tag{3} \sum_n f(n)=\sqrt{2},\quad \quad \sum_n g(n)=0 \end{equation} (these two conditions are equivalent if all the others hold), and if \[ F(\xi)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\sum_n f(n) e^{in\xi} \] satisfies \[ \prod^{\infty}_{j=1} F(2^{-j}\xi) \in L^2(\mathbb{R}), \] then we have an associated wavelet basis: \begin{gather*} \hat\phi(\xi)=\prod^{\infty}_{j=1} F(2^{-j}\xi),\quad \psi(x) = \sum_k g(k)\sqrt{2}\,\phi(2x-k), \\ \langle \phi_{-1\,k},\phi_{0\,n}\rangle= f(n-2k), \\ \langle \psi_{-1\,k},\phi_{0\,n}\rangle= g(n-2k). \end{gather*} If we insist, at the start, that the sequences \( f(n),g(n) \) only have finitely many nonzero terms, the associated \( \psi,\phi \) will have compact support (in that case \( F \), and therefore also \( \prod_{j=1}^\infty F(2^{-j}\xi) \), are entire and of exponential type).

So the question is to find \( f,g \) satisfying all the conditions.

If we set \begin{alignat*}{2} f(2n)&=a(n),\quad& g(2n)&=c(n),\\ f(2n+1)&=b(n),\quad& g(2n+1)&=d(n),\\ \end{alignat*} and define Toeplitz matrices \( A,B,C,D \) (infinite on both sides) by \( A_{nk}=a(n-k),\dots \), and functions \( \alpha,\beta,\gamma,\delta \) by \( \alpha(x)=\sum_n a(n)e^{inx} \), …, which are entire since only finitely many \( a, b,\dots \) are nonzero, then the conditions become \begin{alignat*}{2} \begin{cases} A^*A+C^*C=\unicode{x1D7D9}\\ B^*B+D^*D=\unicode{x1D7D9}\\ A^*B+C^*D=0 \end{cases} &\quad\hbox{or}\quad \begin{cases} |\alpha(x)|^2 + |\gamma(x)|^2=1\\ |\beta(x)|^2 + |\delta(x)|^2 = 1 \\ \overline{\alpha(x)}\,\beta(x) + \overline{\gamma(x)}\, \delta(x)= 0 \end{cases} &\qquad\qquad&(1)\leftrightarrow(1^{\prime}) \\ \\ A^*C+B^*D=0 &\quad\hbox{or}\quad \overline{\alpha(x)} \gamma(x) + \overline{\beta(x)}\,\delta(x) = 0. &\qquad\qquad&(2)\leftrightarrow(2^{\prime}) \end{alignat*} It follows from these last two equations (this is most easily seen on the \( \alpha,\beta,\gamma,\delta \) side) that \[ |\beta(x)|^2= |\gamma(x)|^2 , \quad\hbox{or}\quad B^*B=C^*C, \] and hence \[ |\alpha(x)|^2= |\delta(x)|^2 , \quad\hbox{or}\quad A^*A=D^*D. \] Let \( n_a,n_b,n_c,n_d \) be the widths of the diagonal bands outside which the Toeplitz matrices \( A,B,C,D \) vanish. Then, since \( B^*B=C^*C \) and \( A^*A=D^*D \), we have \[ n_b=n_c,\quad n_a=n_d, \] and, if \( n_a,n_b,n_c,n_d \) are all nonzero, \[ n_a=n_c,\quad n_b=n_d. \] (This because the width of \( B^*B \) is \( 2n_b-1 \), that of \( D^*D \) is \( 2n_d-1 \), and \( B^*B+D^*D=\unicode{x1D7D9} \).) We therefore have \[ n_a=n_b=n_c=n_d. \]

Suppose there exist wavelets associated to \( f,g \). Suppose that \( \phi \) is symmetric about 0, as in all interesting cases up to now. Then \( f(n) \) is symmetric about 0: \( f(-n)=f(n) \). If there are only finitely many nonzero \( f(n) \), this implies that \[ n_a\ne n_b, \] (\( n_a+n_b \) is necessarily odd in this case).

It follows that there are no compactly supported orthonormal wavelet bases with \( \phi \) symmetric about 0 and compactly supported.

In the case of the Haar basis, \( \psi \) is symmetric about \( \frac{1}{2} \). Since symmetry about 0 is not possible, what about symmetry about \( \frac{1}{2} \)? This leads to \[ f(n+1)=f(-n) \] or \[ C = A^*\quad\hbox{(let’s suppose the } f \text{ are real)}. \] But then \( 2 A^*A=\unicode{x1D7D9} \), which implies \[ n_a=1. \] The solution, unique up to permutations and shifts, is then \[ A=C=\frac{1}{\sqrt 2}\,\unicode{x1D7D9}, \quad B=-D=\frac{1}{\sqrt 2}\,\unicode{x1D7D9}, \] which corresponds to the Haar basis. There is no other compactly supported orthonormal wavelet basis associated to a compactly supported function \( \phi \) symmetric about \( \frac{1}{2} \), apart from the Haar basis.

On the other hand, if we drop the symmetry requirement, there are nontrivial examples.

For \( n_a=n_b=n_c=n_d=1 \), for example, we find that, for every \( \lambda,\mu\in\mathbb R \), the matrices \[ A=N^{-1}(\lambda\mu+U), \quad B=N^{-1}(\lambda-\mu U), \quad C=N^{-1}(\mu-\lambda U), \quad D=N^{-1}(1+\lambda\mu U), \] where \( N=[(1+\lambda^2)(1+\mu^2)]^{1/2} \) and where \( U \) is the “shift” matrix, \( U_{nk}=\delta_{n-k+1} \), satisfy equations \( (1^{\prime}) \) and \( (2^{\prime}) \).

If we also impose (3), then \( \mu=\frac{\lambda-1}{\lambda+1} \), and \[ \hat\phi(\xi)=\prod_{j=1}^\infty[ F(2^{-j}\xi)] \] converges, and lies in \( L^2(\mathbb R) , \) where \[ F(\xi)=\frac{1}{2(1+\lambda)^2}\bigl[ \lambda(\lambda-1)+\lambda(\lambda+1 )e^{i\xi}+ (\lambda+1 )e^{2i\xi}-(\lambda-1 )e^{3i\xi}\bigr]. \] The function \( \phi \) is supported in the interval \( [0,3] \) (or in \( [-1,2] \) if we apply a “shift”). Altogether it looks kind of funny. For \( \lambda=2\pm\sqrt{3} \), \( \hat\phi \) decreases faster than \( (1+|\xi|)^{-(1+\varepsilon)} \), and therefore \( \phi \) is continuous.

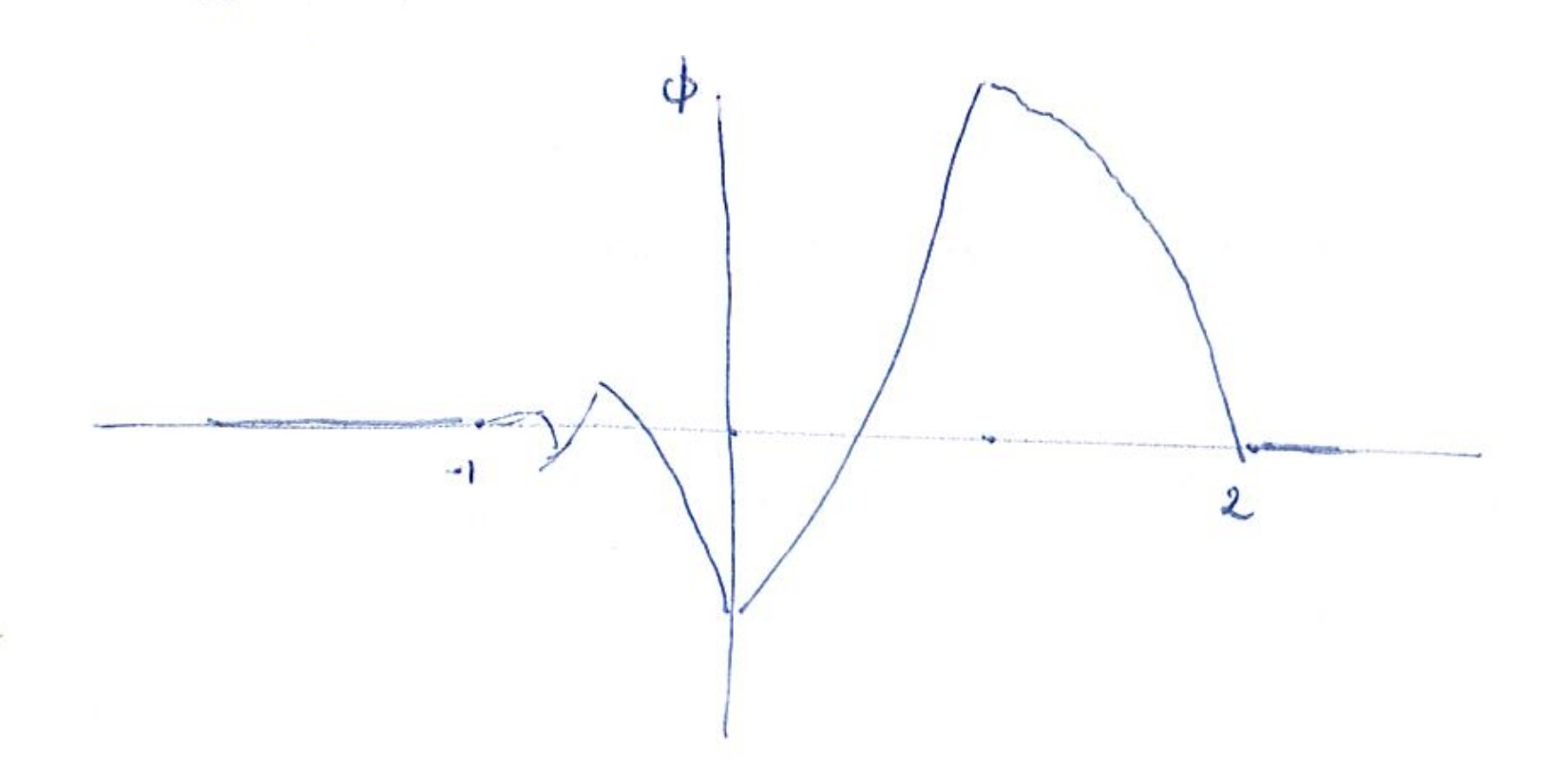

If we draw a graph, it looks like this:

If we move on to \( n_a=2 \), we can find examples of “cuspless” \( \phi \). My conjecture now is that there exist \( \phi\in C^k \) in the class \( n_a=k+1 \).

I had expected that the “vision people” would love a pyramid algorithm recurrence with a finite number of terms, but they’re not very fond of the asymmetry. But perhaps the construction might serve for other things…?

That’s all the news I have.

My best greetings to Anne, and to Guy David!

Ingrid

\[ \star\qquad\star\qquad\star \]

Cher Yves,

Comment vas-tu? Il y a longtemps que je voulais t’écrire, et j’ai un peu honte d’avoir attendu si longtemps. Mais voilà enfin de mes nouvelles.

Ann Arbor nous a fait, à Robert et moi deux offres de “associate professorships” (“with tenure”). Ils m’ont dit qu’ils étaiet fort impressionnés par ta lettre de recommendation, pour laquelle je voudrais encore te remercier. D’autre part, Bell Laboratories aussi m’a fait une offre (Robert y travaille déjà). Il nous faut décider avant le 1er mars (encore une semaine…). Si j’étais la seule à décdier, je crois que je pencherais plutôt vers Ann Arbor: j’aime beaucoup l’endroit, et c’est une bonne université. J’y apprendrais beaucoup plus de math, aussi. D’autre part, Robert est vraiment plus attaché à Bell Labs que je ne croyais (et qu’il ne croyait lui-même d’ailleurs), et, comme je répugne de commencer notre mariage en le séparant de Bell alors qu’il s’y plaît, nous opterons probablement pour la solution Bell. Je crois d’ailleurs que je me plairai beaucoup à Bell aussi: il y a de très bons mathématiciens là aussi, et ils laissent une grande liberté à leurs chercheurs. Tu avais dit que, si nous allions à Ann Arbor, tu viendrais nous rendre visite, Robert et moi et les petits. J’espère que tu viendras aussi nous voir si nous prenons la voie Bell! Je crois que tu trouverais certains des mathématiciens intéressants (Andrew Odlyzko, Ron Graham, Larry Shepp, Jeff Lagarias, Neil Sloane, …). Eux aussi étaient fort impressionnés par ta recommendation… Merci de m’avoir ouvert ces portes!

En attendant de décider tout à fait définitivement (ce qui sera fait cette semaine), j’ai enfin terminé le gros papier, frames (dont j’avais vraiment marre à la fin), et je me suis remis aux ondelettes. L’arrivée du papier de Stéphane Mallat, que je trouve très beau, m’a amenée a réfléchir sur les bases orthonormales d’ondelettes. Je me demandais aussi si un algorithme en “pyramide” comme dans le paper de Mallat, nécessairement devait reposer sur une base d’ondelettes. J’en ai discuté avec des “vision”-peuple ici, et ils semblent penser qu’une propriété d’orthogonalité des sous-espaces de \( \ell^2(\mathbb{Z}) \), qui alors impose l’existence d’une base orthonormale d’ondelettes sous-jacent la “pyramide”, est essentielle. Tout cela m’a aussi amenée à la construction de bases orthonormales d’ondelettes à support compact. (Voilà que moi, qui étais toujours dans les frames, je sombre dans l’orthonormal aussi!) Elles existent, mais les exemples que j’ai trouvés ont une drôle de gueule.

L’idée est la suivante.

Essayons de construire des suites \( f(n), g(n) \) telles que \begin{equation} \tag{1} \sum_k f(n-2k)f^*(\ell-2k) + g(n-2k)g^*(\ell-2k)=\delta_{n\ell}. \end{equation} (au fond, c’est tout ce qui est nécessaire pour qu’une “pyramide” de décomposition \( + \) reconstruction de \( \ell^2(\mathbb{Z}) \) marche.)

On peut alors définir \( G,F:\ell^2(\mathbb{Z})\to\ell^2(\mathbb{Z}) \) par \[ (Fc)_k=\sum_n f(n-2k)c_n, \quad (Gc)_k=\sum_n g(n-2k)c_n, \] Alors \( F^*F+G^*G=\unicode{x1D7D9} \), et on a \[ (F^*)^N F^N+\sum^N_{j=1} F^{*N-j}G^*G F^{N-j} = \unicode{x1D7D9}, \] c.à.d. une décomposition \( + \) reconstruction avec algorithem en pyramide de \( \ell^2(\mathbb{Z}) \). En pratique, on choisira \( f,g \) réels.

Il parait raisonnable (mais non pas nécessaire) de se restreindre au

cas où

\[

F^*\ell^2(\mathbb{Z})\perp

G^*\ell^2(\mathbb{Z})

\]

(il est clair que la somme des 2 espaces est

\( \ell^2 \) dans tous les cas). Cela mènerait (d’après l’intuitions

des

vision people)

à une plus grande “data compaction que le cas non-orthogonal. On

impose donc

\addtocounter{equation}{1}

\begin{equation} \sum_n f(n-2k)\,g^*(n-2l)=0.

\end{equation}

Toutes ces conditions sont évidemment satisfaites si les \( f,g \) sont obtenus à partir d’une base d’ondelettes. D’autre part, si \begin{equation} \sum_n f(n)=\sqrt{2}, \quad \sum_n g(n)=0 \end{equation} (ces 2 conditions sont équivalentes si on a toutes les autres), et si \[ F(\xi)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\sum_n f(n) e^{in\xi} \] satisfait que \[ \prod^{\infty}_{j=1} F(2^{-j}\xi) \in L^2 (\mathbb{R}), \] alors on a une base d’ondelettes associées: \begin{gather*} \hat\psi(\xi)=\prod^{\infty}_{j=1} F(2^{-j}\xi),\quad \psi(x) - \sum_k g(k) \sqrt{2} \phi(2x-k), \\ \langle \phi_{-1\,k},\phi_{0\,n}\rangle= f(n-2k), \\ \langle \psi_{-1\,k},\phi_{0\,n}\rangle = g(n-2k). \end{gather*} Si on impose, au départ, que les suites \( f(n),g(n) \) n’ont qu’un nombre fini de terms non-nuls, alors les \( \psi,\phi \) associés auront un support compact (\( F \), et par conséquent \( \prod_{j=1}^{\infty}, F(2^{-j}\xi) \), est, dans ce cas-là, entier de type exponentiel).

ll s’agit donc de trouver des \( f,g \) satisfaisant toutes les conditions.

Si on définit \begin{alignat*}{2} f(2n)&=a(n),\quad& g(2n)&=c(n),\\ f(2n+1)&=b(n),\quad& g(2n+1)&=d(n),\\ \end{alignat*} et des matrices Toeplitz \( A,B,C,D \) (infinies des 2 côtés) par \( A_{nk}=a(n-k),\dots \), et des fonctions entières (puisque un nombre fini seulement des \( a, b,\dots \) est \( \neq 0 \)) \( \alpha,\beta,\gamma,\delta \) par \( \alpha(x)=\sum a(n)e^{inx} \), …, alors les conditions deviennent \begin{alignat*}{2} \begin{cases} A^*A+C^*C=\unicode{x1D7D9}\\ B^*B+D^*D=\unicode{x1D7D9}\\ A^*B+C^*D=0 \end{cases} &\quad\hbox{ou}\quad \begin{cases} |\alpha(x)|^2 + |\gamma(x)|^2=1\\ |\beta(x)|^2 + |\delta(x)|^2 = 1 \\ \overline{\alpha(x)}\,\beta(x) + \overline{\gamma(x)}\, \delta(x)= 0 \end{cases} &\qquad\qquad&(1)\leftrightarrow(1^{\prime}) \\ \\ A^*C+B^*D=0 &\quad\hbox{or}\quad \overline{\alpha(x)} \gamma(x) + \overline{\beta(x)}\,\delta(x) = 0. &\qquad\qquad&(2)\leftrightarrow(2^{\prime}) \end{alignat*} Une conséquence de ces 2 dernières éq. est (cela se voit le mieux du côté \( \alpha,\beta,\gamma,\delta \) \[ |\beta(x)|^2= |\gamma(x)|^2 , \quad\hbox{ou}\quad B^*B=C^*C, \] et donc \[ |\alpha(x)|^2= |\delta(x)|^2 , \quad\hbox{ou}\quad A^*A=D^*D. \] Soient \( n_a,n_b,n_c,n_d \) la largeur de la bande diagonale en dehors de laquelle les matrices Toeplitz \( A,B,C,D \) sont nulles. Alors, puisque \( B^*B=C^*C \), \( A^*A=D^*D \), \[ n_b=n_c,\quad n_a=n_d, \] et, si tous les \( n_a,n_b,n_c,n_d \neq 0 \), \[ n_a=n_c,\quad n_b=n_d. \] (Ceci parce que la largeur de \( B^*B = 2n_b-1 \), celle de \( D^*D = 2n_d-1 \), et \( B^*B+D^*D=\unicode{x1D7D9} \)). On a donc \[ n_a=n_b=n_c=n_d. \] Supposons qu’il existe des ondelettes associées aux \( f,g \). Supposons que \( \phi \) soit symétrique autour de 0, (comme dans tous les cas intéressants jusqu’à présent). Alors \( f(n) \) est symétrique autour de \( 0: f(-n)=f(n) \). Si il y a un nombre fini de \( f(n) \) nonnuls, cela implique \[ n_a\ne n_b, \] (\( n_a+n_b \) est nécessairement impair dans ce cas-ci).

Il n’y a donc pas de bases orthonormales d’ondelettes à support compact avec \( \phi \) de support compact et symétrique autour de 0.

Dans le cas de la base de Haar, \( \psi \) est symétrique autour de \( \frac{1}{2} \). La symétrie autour de 0 étant exclue, qu’en est-il par la symétrie autour de \( \frac{1}{2} \)? Ceci mène à \[ f(n+1)=f(-n) \] ou \[ C = A^*\quad\text{(supposons les } f \text{ réels)}. \] Mais alors \( 2 A^*A=\unicode{x1D7D9} \), ce qui implique \[ n_a=1. \] L’unique solution (à des permutations et das “shifts” près) est alors \[ A=C=\frac{1}{\sqrt 2}\unicode{x1D7D9}, \quad B=-D=\frac{1}{\sqrt 2}\unicode{x1D7D9}, \] ce qui corresond à la base de Haar. Il n’y a pas d’autre base orthonormale d’ondelettes à support compact associé à une fonction \( \phi \) de support compact, autour de \( \frac{1}{2} \), que la base de Haar.

Si on laisse tomber l’idée de symétrie par contre, il y a des exemples non triviaux.

Pour \( n_a=n_b=n_c=n_d=1 \), par exemple, on trouve que, pour tout \( \lambda,\mu\in\mathbb R \), les matrices \[ A=N^{-1}(\lambda\mu+U), \quad B=N^{-1}(\lambda-\mu U), \quad C=N^{-1}(\mu-\lambda U), \quad D=N^{-1}(1+\lambda\mu U), \] où \( N=[(1+\lambda^2)(1+\mu^2)]^{1/2} \), et où \( U \) est la matrice “shift”, \( U_{nk}=\delta_{n-k+1} \), satisfont les équations \( (1^{\prime}) \) et \( (2^{\prime}) \).

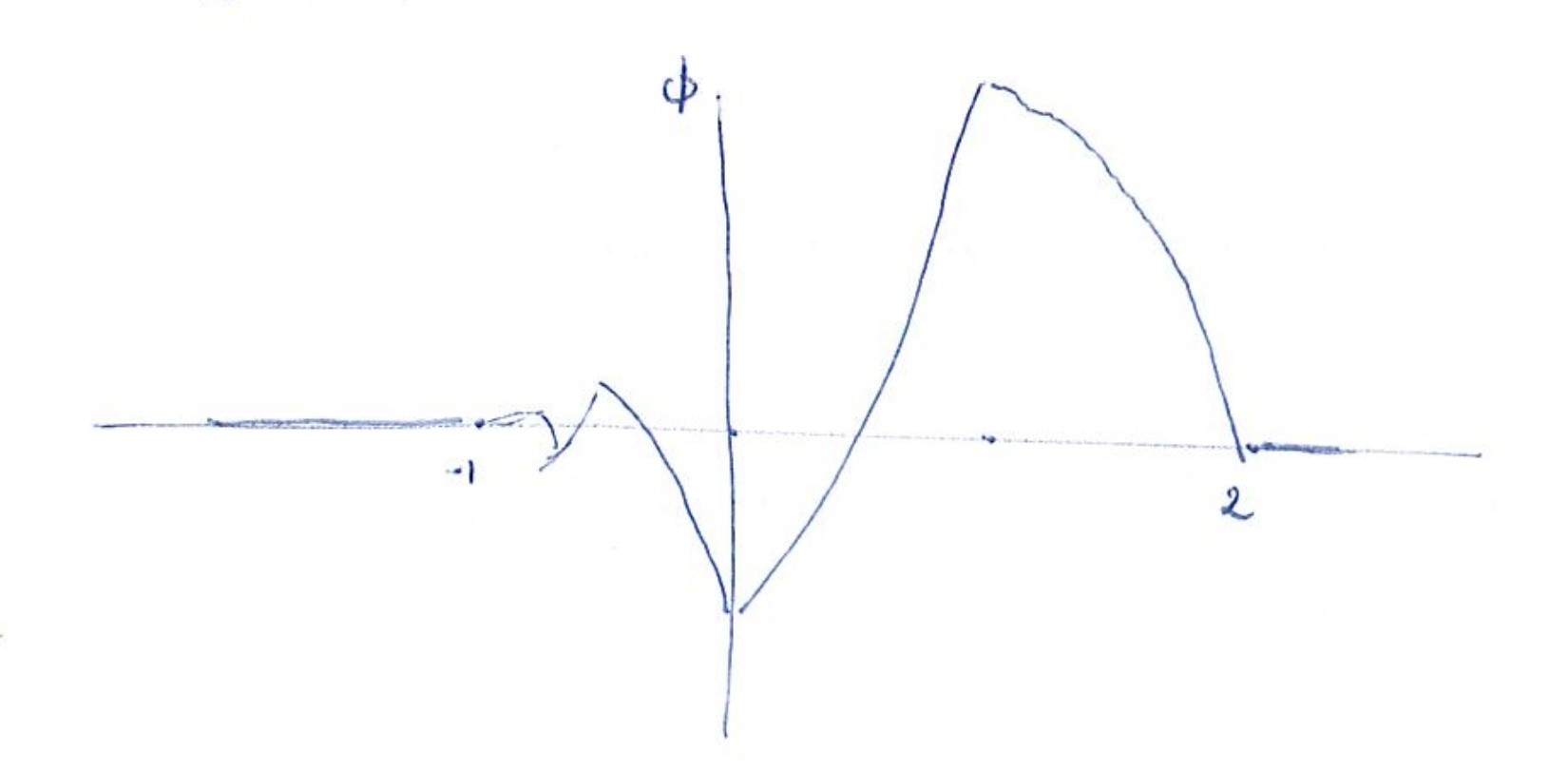

Si on impose en plus (3), alors \( \mu=\frac{\lambda-1}{\lambda+1} \), et \[ \hat\phi(\xi)=\prod_{j=1}^\infty [F(2^{-j}\xi)] \] converge, et est dans \( L^2(\mathbb R) \), où \[ F(\xi)=\frac{1}{2(1+\lambda)^2}\bigl[ \lambda(\lambda-1)+\lambda(\lambda+1 )e^{i\xi}+ (\lambda+1 )e^{2i\xi}-(\lambda-1 )e^{3i\xi}\bigr]. \] La fonction \( \phi \) a comme support l’intervale \( [0,3] \) (ou \( [-1,2] \) si on fait un “shift”). En général elle a une drôle de gueule. Pour \( \lambda=2\pm\sqrt{3} \), \( \hat\phi \) decroît plus vite que \( (1+|\xi|)^{-(1+\varepsilon)} \), et \( \phi \) est donc continue.

Si on fait un graphique, on a

Si on passe à \( n_a=2 \), on arrive à trouver des \( \phi \) sans “cusps”. Ma conjecture, maintenant, est qu’il existe des \( \phi\in C^k \) dans la classe \( n_a=k+1 \).

J’avais espéré que les “vision people” aimeraient une récurrence pour l’algorithme pyramidal avec un nombre fini de termes, mais ils n’aiment pas trop l’assymétrie. Mais elles pourraient peut-être servir à autre chose…?

Voilà toutes mes nouvelles.

Un grand bonjour à Anne, et à Guy David!

Ingrid