by Lisa Traynor

In this note, my aim is to give a glimpse into some of Yasha Eliashberg’s research contributions in symplectic and contact topology that employ the technique of generating functions. In particular, I will give a short overview of some of the main results of the paper Lagrangian intersection theory: Finite-dimensional approach, written by Eliashberg and Gromov [1]. This paper appeared in an AMS Translations Series volume containing a collection of articles written by colleagues of V. I. Arnold on the occasion of the latter’s 60th birthday. In their work, Eliashberg and Gromov systematically explore the possibilities of a finite-dimensional approach, known as the technique of generating functions (or generating families), to problems of Lagrangian and Legendrian intersections, and define invariants of Lagrangian and Legendrian embeddings. In this note, I will also give a reflection of how Eliashberg’s knowledge and ideas about generating functions inspired me in my postdoctoral years and formed the basis of a technique that I have used throughout my mathematical career.

1. History and basic ideas behind generating functions

Symplectic manifolds are always even-dimensional, and Lagrangian submanifolds are central objects of study in symplectic topology. In the classic symplectic manifold of a cotangent bundle, \( T^*M \), a basic example of a Lagrangian manifold is the graph of the differential of a smooth function \( f: M \to \mathbb{R} \): \[ L_f = \{ (x, df(x)): x \in M \} \subset T^*M. \] On a compact \( M \), given two functions \( f_1, f_2: M \to \mathbb{R} \), their associated Lagrangians must intersect, \[ L_{f_1} \cap L_{f_2} \neq \emptyset, \] since \( f_1-f_2: M \to \mathbb{R} \) must necessarily have critical points. Not all Lagrangians are the graphs of differentials of functions \( f:M \to \mathbb{R} \). Even so, the Arnold conjectures, which have motivated a huge amount of research in symplectic topology, roughly assert that the cardinality of the set of intersections of Lagrangian submanifolds should be bounded below by numbers arising from Morse theory.

Nongraphical Lagrangians of \( T^*M \) are plentiful. For example, a Hamiltonian isotopy of a graphical Lagrangian can produce a Lagrangian that is nongraphical. However, it is still possible to describe the Hamiltonian image of a graphical Lagrangian by a “function”, where the function is no longer defined on \( M \) but depends on extra variables. More precisely, the function is defined on a trivial vector bundle over \( M \): \[ F:M \times \mathbb{R}^N \to \mathbb{R}. \] The still-unresolved nearby Lagrangian conjecture, due to Arnold, states that every closed, exact Lagrangian submanifold of the cotangent bundle of a closed manifold is Hamiltonian isotopic to the zero section; if true, this conjecture implies that any closed, exact Lagrangian in this setting would possess a generating function.

In the sibling world of contact topology, contact manifolds are always odd-dimensional, and Legendrian submanifolds are central objects of study. The 1-jet space of a manifold, \( J^1M = T^*M \times \mathbb{R} \), is a classic contact manifold, and the 1-jet of \( f: M \to \mathbb{R} \), \[ \mathcal L_f = \{ (x, df(x), f(x)): x \in M \} \subset J^1M, \] is a basic example of a graphical Legendrian submanifold. The set of graphical Legendrian submanifolds is not preserved under contact isotopies. However, a contact isotopy of a graphical Legendrian submanifold will possess a generating function \[ F:M \times \mathbb{R}^N \to \mathbb{R}. \] If \( F \) generates the Legendrian \( \mathcal L \subset J^1M \), then under the projection \( \pi: J^1M \to T^*M \), \( F \) also generates the immersed Lagrangian \( \pi(\mathcal L) = L \subset T^*M \).

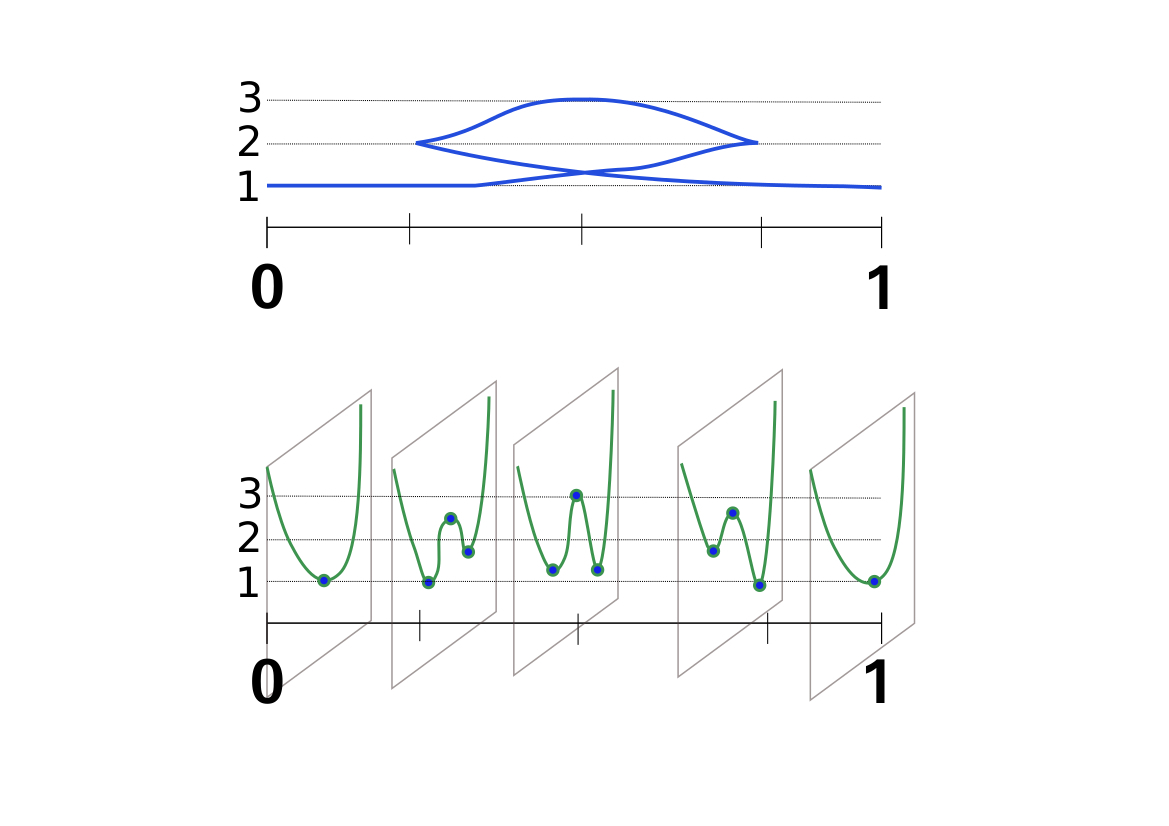

Roughly, the idea of a generating function is to construct a 1-parameter family of functions that encodes a Legendrian/Lagrangian submanifold. As a basic example, Figure 1 illustrates the front, or \( xz \)-projection, of a nongraphical Legendrian submanifold \( \mathcal L \subset T^*S^1 \), where \( S^1 = [0,1]/ 0 \sim 1 \). For this nongraphical Legendrian, we can construct a function \( F: S^1 \times \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R} \) such that as we vary \( x \) and plot the fiber-critical values of the fiber functions \( F_x: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R} \), \( x \in S^1 \), we obtain the front of \( \mathcal L \). Already in this simple example, we see that there are choices. In particular, given a generating function \( F_1: S^1 \times \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R} \) that generates \( \mathcal L \), one can construct another generating function \( F_2: S^1 \times \mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R} \) for \( \mathcal L \) by stabilization: \( F_2(x, \eta_1, \eta_2) = F_1(x, \eta_1) + Q(\eta_2) \), where \( Q: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R} \) is a nondegenerate quadratic form.

The idea of generating functions was known classically, in the time of Jacobi, but was rediscovered by V. I. Arnold in his study of singularities of Lagrangian maps, fronts, and caustics [e2] and by L. Hörmander in the setting of Fourier integral operators [e1]. It took some time for the technique of generating functions to enter into symplectic topology. An important point is that generating functions are defined on noncompact spaces, and it was unclear how to control the behavior of the extra variables at infinity. However, it became clear that Morse-theoretic methods applied under appropriate conditions, such as “quadratic-at-infinity” or, more generally, Eliashberg and Gromov’s “fibration-at-infinity” ([1], Section 0.2.1). Chaperon did implicit constructions of generating functions in his development of the idea of broken geodesics [e3], but the first explicit constructions of generating functions for Lagrangian submanifolds of cotangent bundles towards goals in the field of symplectic topology were done by F. Laudenbach and J.-C. Sikorav [e4]. Around this time, Yu. Chekanov generalized this construction to Legendrian submanifolds of a 1-jet space, but his result was unpublished until 1996 [e12]. C. Viterbo made important developments in constructing symplectic invariants for Lagrangian submanifolds based on the theory of generating functions [e6].

For many years, the importance of generating functions was overshadowed by the successes of the theory of pseudoholomorphic curves, Floer homology theory, and other infinite-dimensional methods. However, A. Givental used generating functions to prove results that were beyond the reach of these methods; see [e11], [e5]. In their article, Eliashberg and Gromov also make some discoveries that go beyond what has been done with the holomorphic techniques. The technique of generating functions continues to be a powerful technique for problems in symplectic and contact topology.

2. Sampling of main results

2.1. Lagrangian intersections

Given two graphical Lagrangian submanifolds \( L_1, L_2 \subset T^*M \), an important goal in symplectic topology is to find lower bounds on the cardinality of the set of intersections, \[ \# (L_1^{\prime} \cap L_2^{\prime}), \] where \( L_1^{\prime}, L_2^{\prime} \) are obtained from the graphical \( L_1, L_2 \) by compact Hamiltonian isotopy. We can reduce this to the case where \( L_1 = L = L_{f} \), for \( f: M \to \mathbb{R} \), \( L_2 = \mathcal O \), the 0-section, and then only consider \( L^{\prime}_f \) obtained by a Hamiltonian isotopy of \( L_f \). Under a Hamiltonian isotopy, at some point \( L_f^{\prime} \) may become nongraphical. In [1], the authors explain how for this nongraphical \( L_f^{\prime} \), \( L_f^{\prime} \cap \mathcal O \) agrees with \( L_{\tilde f} \cap \mathcal O \), where \( \tilde f: M \times \mathbb{R}^N \to \mathbb{R} \) is a stabilization of \( f \). Then they explore how stable Morse–Lusternik–Schnirelmann theory can be applied to find lower bounds for \( \#(L_{f}^{\prime} \cap \mathcal O) \).

Given a function \( f \), we consider its class, \( [f] \), given by stabilization and compact perturbation and define its stable Lusternik–Schnirelmann number, \( \operatorname{stabLuS}(f)_{\mathrm{comp}} \), by minimizing the cardinality of the set of critical points for functions in \( [f] \). Similarly, one can define the stable Morse number, \( \operatorname{stabMor}(f)_{\mathrm{comp}} \), by minimizing the cardinality of the set of critical points for Morse functions in \( [f] \). The number \( \operatorname{stabMor}(f)_{\mathrm{comp}} \) is bounded below by the ranks of relative homology groups of sublevel sets of \( f \) ([1], Proposition 0.2.3), and the number \( \operatorname{stabLuS}(f)_{\mathrm{comp}} \) has a lower bound involving the cuplength of cohomology groups associated to \( f \) ([1], Proposition 0.2.4). When \( f \) defines an \( h \)-cobordism, there is an additional lower bound to \( \operatorname{stabMor}(f)_{\mathrm{comp}} \) given by Whitehead torsion ([1], Proposition 0.2.7).

As a sample of results about Lagrangian intersections, we have:

2.2. Intersection invariants of Legendrian submanifolds

Given a Legendrian submanifold \( \mathcal L \subset J^1M \), and another submanifold \( \mathcal M \subset J^1M \), such that

\( \dim \mathcal L + \dim \mathcal M = \dim J^1M \),

a natural way to define an invariant of \( \mathcal L \) is to try to minimize the number of intersections or transversal intersections between \( \mathcal L \) and \( \mathcal M \):

\[

\begin{aligned}

\cap_{\mathcal M} \mathcal L = \inf_{\mathcal L^{\prime}} \# (\mathcal L^{\prime} \cap \mathcal M), \\

\pitchfork_{\mathcal M} \mathcal L = \inf_{\mathcal L^{\prime}} \# (\mathcal L^{\prime} \pitchfork \mathcal M),

\end{aligned}

\]

where \( \mathcal L^{\prime} \) is the image of \( \mathcal L \) under a compactly supported contact isotopy.

Eliashberg and Gromov find bounds on this intersection number in terms of the stable Morse–Lusternik–Schnirelmann numbers of manifolds, as defined in ([1], Section 0.2.6). For example, as a particular case of ([1], Theorem 0.4.1), where we start with a special subgraphical-Legendrian as defined in ([1], Theorem 0.4.1), we have:

This has interesting applications. For example, when \( M \) has dimension \( n \geq 2 \), for \( N = 1,2, \dots \), Eliashberg and Gromov apply this theorem together with Morse surgery to show that it is possible to construct a Legendrian \( \mathcal L_N \subset J^1M \) diffeomorphic to \( S^n \) such that the projection of \( \mathcal L_N \) to \( M \) has degree 0, and, in fact, can be topologically isotoped to be contained in a single fiber of \( J^1M \), yet no contact isotopy can bring \( \mathcal L_N \) to the complement of any such fiber; in fact, the image of \( \mathcal L_N \) under every contact isotopy necessarily intersects each fiber at more than \( N \) points (and \( 2^N \) points for transversal intersection). In particular, as \( N \) grows, this gives a way to construct an infinite sequence of Legendrian spheres that are mutually contact nonisotopic.

This intersection invariant can be extended to define a self-intersection invariant of \( \mathcal L \subset J^1M \), which again can be bounded by stable Morse-theoretic numbers, ([1], Section 0.4.2). They also define and find lower bounds for a Legendrian linking number between two Legendrian submanifolds, which measures the minimal number of crossings between compact, contact isotopies that move the initial Legendrians to positions that are suitably disjoint, such as to be contained in disjoint Euclidean balls in \( J^1\mathbb{R}^n \) ([1], Sections 0.5.1, 0.5.2).

2.3.thinsp; Homotopy groups of Lagrangians and Legendrians

This result can be combined with known results from work of Waldhausen and Borel on the (stable) homotopy type of \( \operatorname{Diff}_0 \) to obtain, for example:

3. Personal reflections

Eliashberg’s ideas on the generating function technique have had wide influence. This section is not meant to be a survey of all results that grew out of his ideas on generating functions, but rather a reflection on how Eliashberg’s ideas have greatly influenced my own research.

I was a PhD student of Dusa McDuff. My thesis work involved pseudoholomorphic curves. In my graduate school years, Eliashberg and Gromov sketched a proof of the symplectic camel theorem, which used the technique of filling spheres with holomorphic disks. McDuff and I wrote out detailed proofs for filling spheres with holomorphic disks and the 4-dimensional symplectic camel [e7]; this work became the basis for my thesis that explored numerous problems related to the symplectic camel problem [e8]. In spring 1992, soon before defending my PhD, I had the opportunity to attend a workshop at the University of Arkansas that featured a series of talks by Eliashberg. Around this time, Floer and Hofer had constructed invariant homology groups for open subsets of \( \mathbb{R}^{2n} \) [e9]; in Eliashberg’s lecture series, he sketched an alternate construction for symplectic homology that used the finite-dimensional technique of generating functions. I was immediately captivated by this idea of generating functions. I carefully studied the handwritten notes that I took during that workshop and decided to start to learn the generating function technique while I was a postdoc at MSRI during 1992–1993. I became interested in more deeply learning the technique of generating functions, and Eliashberg kindly agreed to be my NSF postdoctoral mentor. In the fall of 1993, I had the incredible opportunity to attend a graduate class on generating functions that Eliashberg taught at Stanford. My first project that used the generating function technique defined symplectic homology groups for open subsets of \( \mathbb{R}^{2n} \) via generating functions [e10].

The finite-dimensional technique of generating functions that I was initially exposed to by Eliashberg has served me well over my career. After studying how generating functions could define symplectic homology for open subsets of \( \mathbb{R}^{2n} \), I went on to use generating functions to define invariants of Legendrian links [e13], [e14]. At some point, I and others started to use the term generating family instead of generating function as a shortening of the longer phrase generating family of functions: due to the common use of the term generating function in physics and combinatorics, I now prefer the term generating family to avoid confusion when communicating beyond the fields of symplectic and contact topology. As a sample of some results, Josh Sabloff and I found how the technique of generating families could be applied to understand quantitative measurements of slices of Lagrangian submanifolds [e15], the length of a Lagrangian cobordism [e18], and obstructions to the existence of Lagrangian cobordisms between Legendrian submanifolds [e16]. Frédéric Bourgeois, Sabloff, and I showed how the technique of generating families could be used to study the geography problem for Legendrian submanifolds, [e17]. More recently, as a consequence of participating in the Floer Homotopy Theory program at SLMath in Fall 2022, I began to better understand some of the ideas that Eliashberg and Gromov had written about in their work on generating functions, which had appeared almost 25 years before. Currently, Hiro Lee Tanaka and I have defined and are currently exploring a stable homotopy invariant for Legendrian submanifolds that can be defined via generating families [e19].

I am always appreciative of Yasha Eliashberg’s kindness and generosity of ideas; he has always been willing and able to explain difficult ideas to me in ways that I could understand. I finished my PhD at a time when there were not many women research mathematicians, and I could easily have been discouraging from pursuing a career that involved serious research. I will always be thankful for the mathematical doors that were opened to me through my interactions with Yasha.