by Hansjörg Geiges

1. Introduction

- filling by holomorphic discs;

- (convex) symplectic filling of contact manifolds;

- (concave) symplectic filling, or symplectic caps;

- filling of “holes” in contact manifolds.

Indeed, “contributions” is a bit of an understatement. In all four cases, Eliashberg almost single-handedly invented the concept and made the crucial first steps, leaving a whole fruitful area to be explored by us lesser minds.

The number of self-citations in this essay should not be interpreted as vanity on the part of the author, but rather as a testimony to Yasha’s tremendous influence on my mathematical development. The times when I was working close to him — during my two years at Stanford (1992–1994) and the couple of months when I hosted Yasha as Kloosterman Professor at Leiden University in 2001 — had long-lasting effects on my mathematical thinking. The inspiration I have drawn from reading Yasha’s papers are beyond measure, a fact even noticed by my late mother, who read all my papers to the extent of finding the occasional misprint, and thus was acutely aware of the countless references I have been making to Eliashberg’s work. I also recall vividly (and somewhat regretfully) that the one result of mine that seems to have excited Yasha the most was a construction of Engel structures on 4-manifolds I showed to him in Leiden. If I had known earlier, I might have decided against publishing it merely as a passing remark in a review for Mathematical Reviews.

From the topologist’s point of view, the most striking aspect of Eliashberg’s work I am going to survey is the fact that these results, which appear to be intrinsic to symplectic and contact topology, actually have applications in “pure” differential and geometric topology.

Filling by holomorphic discs has led to a new proof of Cerf’s theorem that every diffeomorphism of the 3-sphere \( S^3 \) extends to a diffeomorphism of the 4-ball. This implies, in particular, that 4-spheres with exotic differentiable structures — if such exist — can definitely not be constructed by an exotic gluing of two 4-balls, in contrast with the situation in higher dimensions.

The construction of symplectic caps was the keystone in the Kronheimer–Mrowka gauge-theoretic programme for proving that every nontrivial knot \( K \) in \( S^3 \) has property P, which means that every nontrivial surgery along \( K \) yields a 3-manifold that is not simply connected. Previous to the work of Perelman it had been a sensible question to ask whether a counterexample to the 3-dimensional Poincaré conjecture might be constructible via a single Dehn surgery on \( S^3 \).

2. Filling by holomorphic discs

The method of filling by holomorphic discs was outlined by Eliashberg in [2]. The general ideas behind this method fall into the framework of Gromov’s theory of pseudoholomorphic curves in symplectic manifolds [e6], and the relevant analysis has since been worked out in all detail; see [e29], [e14], [e18], [e27], [e12].

2.1. The standard filling of \( S^2\subset S^3 \)

The most simple example of a filling by holomorphic discs is provided by the unit sphere \( S^3\subset\mathbb{C}^2 \). Let \( (z_1,z_2) \) be Cartesian coordinates on \( \mathbb{C}^2 \), and write \( z_j=x_j+\mathrm{i} y_j \). Then \( S^3 \), away from the poles \( \{y_2=\pm 1\} \), is foliated by 2-spheres \( S^2_b=S^3\cap\{ y_2=b\} \), \( \,b\in (-1,1) \). Each of these 2-spheres, in turn, is foliated away from the poles \[ p_b^{\pm}:=\{z_2=\pm\sqrt{1-b^2}+\mathrm{i} b\}\subset S^2_b \] by circles \( S^2_b\cap\{x_2=a\} \), \( \,a\in(-\sqrt{1-b^2},\sqrt{1-b^2}) \). These circles bound the obvious holomorphic discs \( D^4\cap\{z_2=a+\mathrm{i} b\} \) inside the 4-ball \( D^4 \), and this family of discs foliates the 3-ball \( D^3_b=D^4\cap\{y_2=b\} \) away from \( p_b^{\pm} \).

On \( S^3 \) we can consider the tangent 2-plane field \( \xi\subset TS^3 \) made up of the complex lines \( \xi_p\subset T_pS^3\subset T_p\mathbb{C}^2 \). The strict pseudoconvexity of the hypersurface \( S^3\subset\mathbb{C}^2 \) translates into saying that this plane field is what is called a contact structure on \( S^3 \): a nowhere integrable 2-plane field. The intersection \( TS^2_b\cap\xi \) defines a 1-dimensional foliation of \( S^2_b \), with singularities at the complex points \( p \) of \( S^2_b \) where the tangent plane \( T_pS^2_b \) is a complex line in \( \mathbb{C}^2 \), and hence coincides with the complex line \( \xi_p \). This singular 1-dimensional foliation is called the characteristic foliation of \( S^2_b\subset (S^3,\xi) \). In the case at hand, this foliation has a focus type singularity at either pole \( p_b^{\pm} \); such complex points are called elliptic.

The notion of “elliptic point” can be extended to an arbitrary (real) surface \( \Sigma\subset\mathbb{C}^2 \), not necessarily being contained in a pseudoconvex hypersurface, by a bundle-theoretic discussion involving the Graßmannian of complex lines in the tangent bundle of \( \mathbb{C}^2 \). In 1965, in a paper concerned with real submanifolds of \( \mathbb{C}^n \), Bishop [e2] showed that a punctured neighbourhood of an elliptic point of \( \Sigma\subset\mathbb{C}^2 \) admits a foliation by circles spanning embedded holomorphic discs, just as in the standard example above. Thanks to the intersection properties of holomorphic discs in an ambient complex 2-dimensional space, this local filling is actually unique, and the discs are pairwise disjoint.

2.2. The symplectic setting

Eliashberg’s “filling by holomorphic discs” is really a filling by pseudoholomorphic discs. Here is a brief layout of the setting. Let \( (W,J) \) be a compact almost complex manifold of real dimension 4, with boundary \( M=\partial W \). The manifold \( W \) is oriented by \( J \), and \( M \) inherits the boundary orientation.

The 2-plane distribution \( \xi\subset TM \) of complex lines is likewise oriented by \( J \), and hence has a well-defined coorientation. This means that we can write \( \xi=\ker\alpha \) with \( \alpha \) a 1-form on \( M \), unique up to multiplication with a positive function.

The boundary \( M \) is called \( J \)-convex (or Levi convex) if \( \mathrm{d}\alpha \) is positive on \( \xi \). In particular, this implies that \( \alpha\wedge\mathrm{d}\alpha > 0 \). A 1-form on a 3-manifold with this property that \( \alpha\wedge\mathrm{d}\alpha > 0 \) is called a contact form, and the corresponding plane field \( \xi=\ker\alpha \), a contact structure. The condition on \( \alpha \) expresses the nonintegrability of \( \xi \).

Conversely, one may start with a 3-dimensional contact manifold \( (M,\xi) \) and ask whether it is the \( J \)-convex boundary of a compact almost complex manifold \( (W,J) \). This is not always the case, but when it is, it is equivalent (in this dimension!) to the following symplectic notion.

A 2-form \( \omega \) on a 4-dimensional oriented manifold is called a symplectic form if it is closed (\( \mathrm{d}\omega=0 \)) and nondegenerate (\( \omega\wedge\omega > 0 \)). A compact symplectic 4-manifold \( (W,\omega) \) is a weak symplectic filling of \( (M,\xi) \) if \( \partial W=M \) (as oriented manifolds) and \( \omega|_{\xi} > 0 \). An almost complex structure \( J \) on \( (W,\omega) \) is said to be \( \omega \)-tame if \( \omega \) is positive on complex lines in \( (TW,J) \).

After having gone through this desert of definitions, we can now formulate the claimed equivalence (see [e13]): A closed 3-dimensional contact manifold \( (M,\xi) \) is weakly symplectically fillable if and only if it is the \( J \)-convex boundary of a compact symplectic manifold \( (W,\omega) \), with \( J \) an \( \omega \)-tame almost complex structure. One direction is straightforward, for if \( (M,\xi) \) is a \( J \)-convex boundary, meaning that \( \xi \) is made up of complex lines, then \( \omega|_{\xi} > 0 \) by the tameness condition. Conversely, if \( (M,\xi) \) has a weak symplectic filling, one may rescale the contact form \( \alpha \) by a function \( M\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^+ \) such that \( \mathrm{d}\alpha|_{\xi}=\omega|_{\xi} > 0 \). One then chooses an \( \omega \)-tame \( J \) on \( \xi \) and on its \( \omega \)-orthogonal complement in \( TW|_M \). This can be extended to an \( \omega \)-tame \( J \) on all of \( W \) by the contractibility of the space of \( \omega \)-tame almost complex structures. For this \( J \), the boundary \( M \) is \( J \)-convex by construction.

2.3. Disc fillings

The following result of Eliashberg [2] and Gromov [e6] shows that for 2-spheres the local Bishop filling can be extended globally, even in the symplectic setting. For domains in \( \mathbb{C}^2 \) this global extension had been proved earlier by Bedford–Gaveau [e5].

Then the complement \( S\setminus\{p^-,p^+\} \) is foliated by circles that bound \( J \)-holomorphic discs in \( W \). These discs are embedded, disjoint, and they fill an embedded ball \( D^3\subset W \).

The fact that the holomorphic discs foliate \( D^3\subset W \) means that the 1-form \( \beta \) on \( D^3 \) that defines the complex tangencies \( \eta \) to \( D^3 \) satisfies \( \mathrm{d}\beta|_{\eta}=0 \); such a ball in \( W \) is called Levi flat (as opposed to the Levi convexity of \( M\subset W \)). The assumption on the absence of \( J \)-holomorphic spheres is made to guarantee that as one tries to extend the local Bishop family, no “bubbling” phenomenon can arise.

Theorem 2.1 only gives a flavour of Eliashberg’s method of filling by holomorphic discs. Eliashberg introduced notions of partial or maximal fillings of surfaces other than the 2-sphere, and these have important applications as well; see Section 2.5.

2.4. Proof of Cerf’s theorem

The ingenious proof of Cerf’s theorem [e3] presented here was proposed by Eliashberg in [5]. Besides the filling by holomorphic discs it uses Eliashberg’s classification of contact structures on \( S^3 \). Full details of a slightly modified version of Eliashberg’s argument can be found in [e23].

2.4.1. From a diffeomorphism to a contactomorphism

The starting point for Eliashberg’s proof is his classification of tight contact structures on \( S^3 \). As in Section 2.1 we consider the contact structure on \( S^3\subset\mathbb{C}^2 \) made up of the complex lines in the tangent spaces. For clarity, we now write \( \xi_{\mathrm{st}} \) for this standard contact structure on \( S^3 \). In Eliashberg’s dichotomy [1] of tight and overtwisted contact structures on 3-manifolds, \( \xi_{\mathrm{st}} \) falls into the tight class. We do not (yet) need to bother ourselves with the definition of tight vs. overtwisted (but see Section 2.5 below); for the present purposes it suffices to accept that these characterisations are invariant under diffeomorphisms.

Now, in [5] Eliashberg proved that \( \xi_{\mathrm{st}} \) is the unique tight contact structure on \( S^3 \) up to homotopy. Together with Gray’s stability theorem, which says that any homotopy of contact structures on a closed manifold is induced by a diffeotopy of the manifold itself, this entails the following result.

Such an isotopy from a given diffeomorphism of \( S^3 \) to a contactomorphism of \( (S^3,\xi_{\mathrm{st}}) \) can be swept out over a collar neighbourhood of \( S^3 \) in \( D^4 \). Hence, in order to prove Cerf’s theorem, it suffices to extend any given contactomorphism of \( (S^3,\xi_{\mathrm{st}}) \) to a diffeomorphism of \( D^4 \) (or, what we shall actually do, isotope it to a diffeomorphism that extends).

2.4.2. The characteristic foliation

Recall from Section 2.1 that away from the poles \( \{y_2=\pm 1\} \) we have a foliation of \( S^3 \) by the 2-spheres \( S^2_b \). On each of these 2-spheres we consider the characteristic foliation \( \mathcal{F}_b:=TS^2_b\cap\xi_{\mathrm{st}} \). Away from the poles \( p_b^{\pm}\in S^2_b \), this characteristic foliation is spanned by the nonsingular vector field \[ (x_1x_2+by_1)\partial_{x_1}+(y_1x_2-bx_1)\partial_{y_1}- (x_1^2+y_1^2)\partial{x_2}.\] So the characteristic foliation is essentially a longitudinal foliation between the two singular poles, with a latitudinal twist depending on \( b \).

If \( \varphi \) is a contactomorphism of \( (S^3,\xi_{\mathrm{st}}) \), then \( \varphi(\mathcal{F}_b) \) equals the characteristic foliation \( T(\varphi(S^2_b))\cap\xi_{\mathrm{st}} \) of the image sphere \( \varphi(S^2_b) \). This is the crucial point that will allow us to extend \( \varphi \) to a diffeomorphism of \( D^4 \). Here, thanks to the contact analogue of the disc theorem, we may assume without loss of generality that \( \varphi \) is the identity in a neighbourhood of the unknot in \( S^3 \) formed by the poles of \( S^3 \) and the poles of the \( S^2_b \).

2.4.3. Extension via holomorphic filling

As we have seen in Section 2.1, each of the punctured spheres \( S^2_b\setminus\{p_b^{\pm}\} \) comes with a foliation \( \mathcal{C}_b \) by circles of latitude \( S^2_b\cap\{x_2=a\} \), \( a\in(-\sqrt{1-b^2},\sqrt{1-b^2}) \), bounding holomorphic discs in \( D^4 \). This foliation is obviously transverse to the characteristic foliation \( \mathcal{F}_b \), since the latter always has a nonzero component in longitudinal direction.

There is indeed a deeper reason for this transversality. The hypersurface \( S^3\subset\mathbb{C}^2 \) is strictly pseudoconvex, so the maximum principle prevents holomorphic curves from being tangent to \( S^3 \) from the interior, even at a boundary point of the holomorphic curve. Since the characteristic foliation \( \mathcal{F}_b \) is defined by the intersection of \( TS^2_b \) with the complex lines \( \xi_{\mathrm{st}} \), a tangency of the boundary of a holomorphic curve with \( \mathcal{F}_b \) would imply tangency with \( \xi_{\mathrm{st}} \), and hence with \( S^3 \).

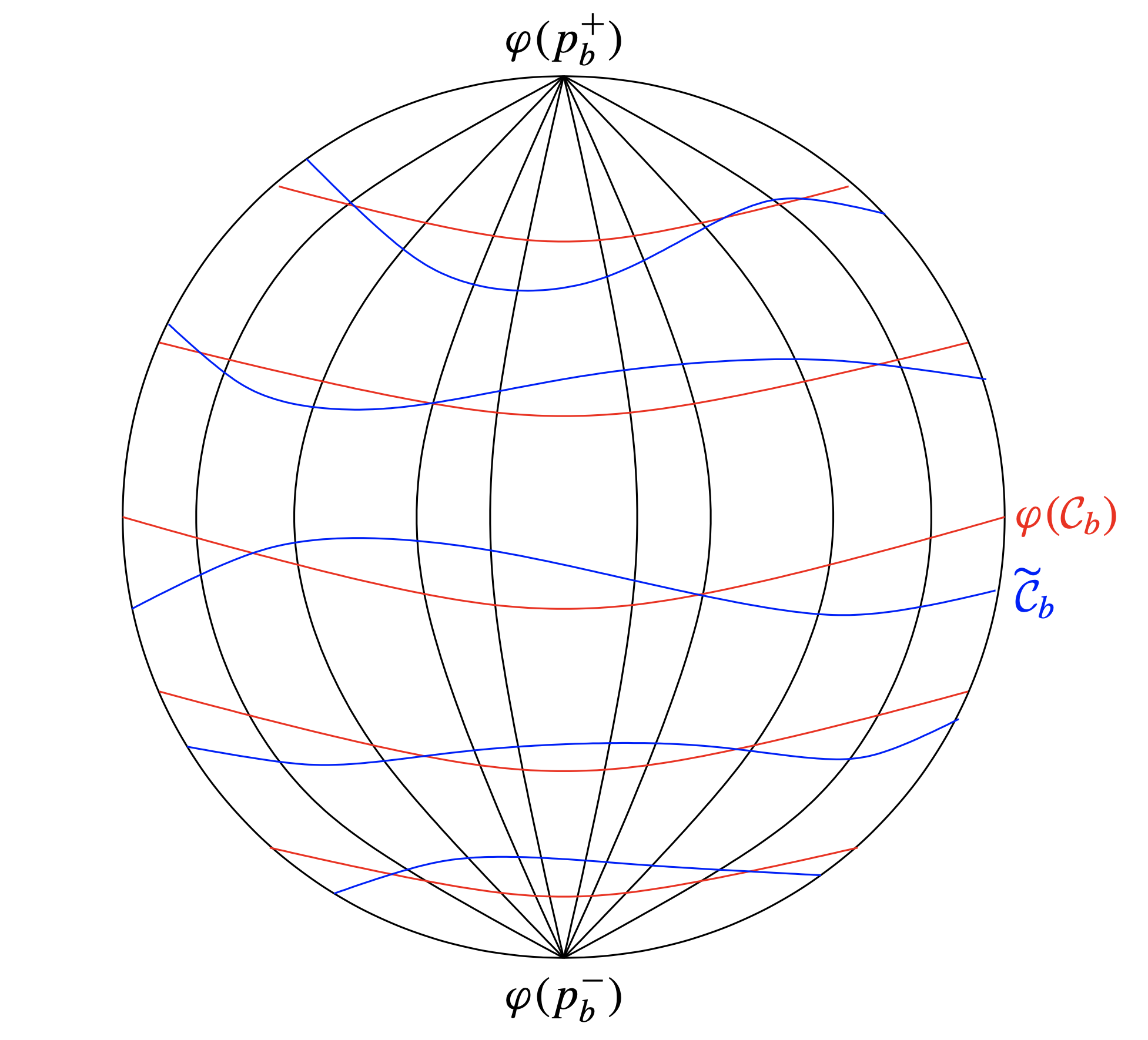

Now, let \( \varphi \) be a contactomorphism of \( (S^3,\xi_{\mathrm{st}}) \) as above. Then the punctured sphere \( \varphi(S^2_b\setminus\{p_b^{\pm}\}) \) comes with two foliations transverse to its characteristic foliation \( \varphi(\mathcal{F}_b) \). The first one is simply the image foliation \( \varphi(\mathcal{C}_b) \). The second foliation \( \widetilde{\mathcal{C}}_b \) is given by the boundaries of holomorphic discs filling \( \varphi(S^2_b) \), thanks to Eliashberg’s filling theorem. See Figure 1, where \( \varphi(\mathcal{F}_b) \) is the longitudinal foliation.

An isotopy of \( \varphi \) to a diffeomorphism \( \tilde{\varphi} \) sending \( \mathcal{C}_b \) to \( \widetilde{\mathcal{C}}_b \) (for all \( b \)) can then be found by isotoping \( \varphi(\mathcal{C}_b) \) to \( \widetilde{\mathcal{C}}_b \) along the leaves of \( \varphi(\mathcal{F}) \). This new diffeomorphism \( \tilde{\varphi} \) of \( S^3 \) sends boundaries of holomorphic discs to boundaries of holomorphic discs; near the unknot of poles in \( S^3 \) (consisting of points that are not boundaries of such discs) \( \tilde{\varphi} \) is still the identity. Both families of discs foliate the 4-ball \( D^4 \).

By an elementary argument, any diffeomorphism of \( S^1 \) extends to a diffeomorphism of \( D^2 \). The same is true for families of such diffeomorphisms thanks to a result of Smale [e1], which says that the restriction homomorphism \( \mathrm{Diff}(D^2)\rightarrow\mathrm{Diff}(S^1) \) is a Serre fibration with contractible fibre. This now allows us to extend \( \tilde{\varphi} \) to a diffeomorphism of \( D^4 \).

2.5. Symplectic fillability implies tightness

As mentioned earlier, contact structures in dimension 3 fall into two classes: tight and overtwisted. In order to define these classes, we need to consider knots in a given contact 3-manifold \( (M,\xi) \). A knot \( K\subset (M,\xi) \) is called Legendrian if \( K \) is tangent to \( \xi \). The contact structure then determines the contact framing of \( K \), i.e., a preferred parallel \( K^{\prime} \) given by pushing \( K \) in the direction of the contact planes along \( K \). If \( K \) is homologically trivial and hence bounds a Seifert surface \( \Sigma \), the intersection number of \( K^{\prime} \) with \( \Sigma \) is a contact isotopy invariant of \( K \), called its Thurston–Bennequin invariant \( \mathtt{tb}(K) \).

Further, the plane field \( \xi \), when restricted to \( \Sigma \), admits a trivialisation. The number of turns of the tangent vector to \( K \) relative to this trivialisation, as one goes once along \( K \), is an invariant of the oriented knot \( K \) that, in general, depends on the relative homology class \( [\Sigma]\in H_2(M,K) \). If the Euler class of the contact structure (regarded as a 2-plane bundle) is trivial, this dependence disappears. This invariant is called the rotation number \( \mathtt{rot}(K,[\Sigma]) \).

Now we say that \( (M,\xi) \) is overtwisted if there is a Legendrian unknot \( K \) with \( \mathtt{tb}(K)=0 \); if no such unknot exists, the contact structure is tight.

In [5], Eliashberg showed how to simplify the characteristic foliation of an embedded closed surface \( S\subset M \), using a process known as Giroux elimination, provided the contact structure \( \xi \) is tight. This leads to a bound on the Euler class of \( \xi \) in terms of the minimal genus of surfaces representing a given homology class. Similar arguments, applied to the Seifert surface \( \Sigma \), yield the Bennequin inequality \[ \mathtt{tb}(K)+|\mathtt{rot}(K,[\Sigma])|\leq -\chi(\Sigma),\] where \( \chi \) denotes the Euler characteristic. Observe that this inequality is obviously violated by a Legendrian unknot with \( \mathtt{tb}(K)=0 \). Some of the key ideas were developed earlier by Bennequin [e4], who was the first to show that the standard contact structure \( \ker(\mathrm{d} z+x\,\mathrm{d} y) \) on \( \mathbb{R}^3 \) is tight, and hence not diffeomorphic to any overtwisted contact structures on \( \mathbb{R}^3 \) (those names did not exist in 1983, but the concepts were there).

This derivation of the Bennequin inequality in the tight case does not rely on the filling by holomorphic discs, but a precursor result in [2] does. Using partial fillings by holomorphic discs, Eliashberg obtained counts on the complex points of a surface embedded in a \( J \)-convex boundary, which then yield a Bennequin inequality as above in this more restricted setting of weakly symplectically fillable contact manifolds. This has the following fundamental consequence.

The proof is an immediate consequence of the Bennequin inequality, as noted above. Of course, matters are not as simple as this précis suggests. For a complete proof of this theorem, providing all the analytic details that were not explained in [2], see Zehmisch’s amazing diploma thesis [e17].

2.6. Other applications

Here is a sample of other applications of the filling-by-holomorphic-discs method, without any attempt at completeness.

(1) There is a deep interplay between contact manifolds and their symplectic fillings (if such exist). On the one hand, the existence of certain fillings imposes restrictions on the contact structure; on the other, a contact structure on the boundary may impose restrictions on the topological or the symplectic type of the filling. A complete account of this still active area of research is beyond this essay, so here I restrict my attention to two applications from Eliashberg’s original paper [2] that directly use holomorphic disc fillings. In Section 3 I say a bit more about the situation in higher dimensions.

(1a) Let \( (W,J) \) be a compact almost complex 4-manifold

not containing any nonconstant \( J \)-holomorphic spheres, and

with \( J \)-convex boundary \( \partial W=S^3 \). Then \( W \) is diffeomorphic

to a 4-ball \( D^4 \). The idea of the proof is that one has a foliation of

\( S^3 \) (minus two poles) by 2-spheres, each of which is filled by

a Levi flat 3-ball coming from a disc filling. One then needs to

argue that these 3-balls actually foliate \( W \).

(1a\( ^\prime \)) Using results of

McDuff

[e7]

on \( J \)-holomorphic spheres

and how to blow them down, the previous result can be sharpened to say

that without the assumption on the absence of \( J \)-holomorphic spheres,

the filling \( W \) must be a blow-up of \( D^4 \), that is, diffeomorphic

to a connected sum \( D^4\mathbin{\#} k\overline{\mathbb{C}\mathrm{P}}^2 \).

(1b) A fairly direct consequence is that in the setting of (1a), the contact structure on the boundary must be the standard structure \( \xi_{\mathrm{st}} \), i.e., diffeomorphic to the one defined by the complex tangencies of \( S^3\subset\mathbb{C}^2 \). By Gray stability, the contact structure is not affected by a perturbation of \( J \), and a suitable such perturbation allows one to find a \( J \)-convex function \( h \) on \( D^4 \) with a single critical point (the minimum), and \( \partial D^4 \) a level set of \( h \). Up to postcomposing with a diffeomorphism of \( \mathbb{R} \), you may think of a \( J \)-convex function as a function with \( J \)-convex level sets.

Near the minimum of \( h \), the almost complex structure can be made integrable, and the level sets biholomorphically equivalent to round spheres in \( \mathbb{C}^2 \). Then, again by Gray stability, all level sets of \( h \) carry the standard contact structure \( \xi_{\mathrm{st}} \).

(1b\( ^\prime \)) In [5], Eliashberg sharpened the result of (1b) by proving that \( \xi_{\mathrm{st}} \) is the unique tight contact structure on \( S^3 \). As we have seen, this result is instrumental in Eliashberg’s proof of Cerf’s theorem.

(1b\( ^{\prime\prime} \)) Thanks to the equivalence formulated in Section 2.2, we may rephrase this as follows: Any weak symplectic filling \( (W,\omega) \) of \( (S^3,\xi_{\mathrm{st}}) \) is diffeomorphic to the 4-ball, provided \( (W,\omega) \) is symplectically aspherical, that is, \( \omega \) vanishes on spherical elements in \( H_2(W) \). In the next section we will discuss an extension of this result to higher dimensions; as we shall see, this requires a stronger notion of symplectic filling.

(2) The famous symplectic camel theorem was stated by Eliashberg and

Gromov

([4], Section 3.4.B),

together with a sketch of a proof

using filling by holomorphic discs. For further details, see

[e9].

The camel theorem, in the spirit of Matthew 19:24,

says the following. In \( \mathbb{R}^4 \) with

the standard symplectic form \( \omega_0=\mathrm{d} x_1\wedge\mathrm{d} y_1+

\mathrm{d} x_2\wedge\mathrm{d} y_2 \), consider, for some \( r > 0 \), the “punctured membrane”

\[ \bigl\{(x_1,0,x_2,y_2): x_1^2+x_2^2+y_2^2\geq r^2\bigr\}.\]

Then a 4-ball of radius \( R > r \) cannot be isotoped symplectically

through the hole in this membrane, that is, there is no symplectic isotopy

in the complement of the punctured membrane

that starts with an inclusion of the ball in the

half-space \( \{y_1 < 0\} \) and ends with an inclusion in the half-space

\( \{y_1 > 0\} \). This result is related but not equivalent to

Gromov’s nonsqueezing theorem

[e6],

[e29].

(3) A local Lagrangian 2-knot in \( (\mathbb{R}^4,\omega_0) \), with symplectic form \( \omega_0 \) as in (1), is an embedding \( i:\mathbb{R}^2\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^4 \) with \( i^*\omega_0=0 \) (the Lagrange property) and \( i \) equal to the inclusion \[ i_0: (x_1,x_2)\mapsto (x_1,0,x_2,0) \] outside a compact subset of \( \mathbb{R}^2 \). Eliashberg–Polterovich [7] showed that the space of local Lagrangian 2-knots in \( \mathbb{R}^4 \) is contractible. In particular, any local Lagrangian 2-knot is isotopic to \( i_0 \) via a compactly supported Hamiltonian isotopy of \( \mathbb{R}^4 \). For an outline of the proof and the current state of the art, see [e30].

3. Convex and concave symplectic fillings

3.1. Strong symplectic fillings of spheres

The extension of (1b\( ^{\prime\prime} \)) to higher-dimensional spheres requires the notion of a strong symplectic filling \( (W^{2n},\omega) \) of a contact manifold \( (M^{2n-1},\xi) \). First of all, \( (W,\omega) \) being symplectic means that \( \omega \) is a closed 2-form whose \( n \)-fold wedge product with itself is a volume form on the oriented manifold \( W \). A contact structure \( \xi \) in higher dimensions is a hyperplane field defined as the kernel of a 1-form \( \alpha \) with the property that \( \alpha\wedge(\mathrm{d}\alpha)^{n-1} \) is a volume form on the oriented manifold \( M \). Finally, the strong filling property requires that

- \( M \) be oriented as the boundary of \( W \);

- there be a vector field \( X \) defined near \( \partial W=M \), pointing outwards along the boundary and satisfying \( L_X\omega=\omega \) (i.e., the flow of \( X \) expands \( \omega \) exponentially);

- the contact structure be given by \( \xi=\ker(i_X\omega) \).

For \( n > 2 \), this is equivalent to requiring that \( \omega|_{\xi} \) be in the conformal class of \( \mathrm{d}\alpha|_{\xi} \) (which only depends on \( \xi \)); see [e8] or [e13]. In all dimensions, a strong filling implies \( J \)-convexity of the boundary for a suitable \( \omega \)-tame \( J \). In particular, for \( n=2 \), a strong filling is also a weak filling.

The standard contact structure \( \xi_{\mathrm{st}} \) on \( S^{2n-1} \) is again the one defined by the complex tangencies of \( S^{2n-1}\subset\mathbb{C}^n \).

Here is the promised higher-dimensional version of (1b\( ^{\prime\prime} \)), whose proof can be found in [e8].

The study of the diffeomorphism type of symplectic fillings continues to be an active area of research; let me immodestly just cite [e28] for some relatively recent developments.

Theorem 3.1 can be used as a tool to detect “exotic” contact structures on \( S^{2n-1} \). By this I mean a contact structure \( \xi \) on \( S^{2n-1} \) that is homotopic to \( \xi_{\mathrm{st}} \) as a complex vector bundle, but not diffeomorphic to it. To make sense of this statement, one needs to observe that if we write the contact structure as \( \xi=\ker\alpha \), the symplectic bundle structure \( \mathrm{d}\alpha|_{\xi} \) induces a unique complex bundle structure up to homotopy (and independent of the choice of \( \alpha \)). This is called the almost contact structure underlying \( \xi \).

Indeed, if \( \xi \) is a homotopically standard contact structure on \( S^{2n-1} \)

that admits a strong symplectic filling not diffeomorphic

to a ball, then \( \xi \) must be exotic by Theorem 3.1.

For the 3-sphere, the existence of an exotic contact structure

is due to Bennequin

[e4],

who constructed an overtwisted

contact structure in the homotopy class of \( \xi_{\mathrm{st}} \). On spheres

of dimension \( 4k+1 \), exotic contact structures were found by

Eliashberg

[3].

(In case you wonder what “contact properties”

a symplectic manifold might have: Yasha once confessed to me that

the title of that paper had been corrupted by the editors.)

In those dimensions there are only finitely many homotopy classes of almost contact structures, whereas in dimensions \( 4k+3 \) there are infinitely many, which requires a more subtle homotopy-theoretic argument to find exotic contact structures. This was done in [e11] and [e20], using Brieskorn spheres (with their natural fillings) and plumbings. For a beautiful survey on Brieskorn manifolds in contact topology, including a discussion of finer contact invariants that allow one to distinguish exotic contact structures amongst one another, see [e25].

3.2. Symplectic caps

We have seen in Section 2.5 that the existence of a symplectic filling (even in the weak sense) imposes restrictions on the contact structure on the boundary. Specifically, it prevents overtwistedness, and this is also true in higher dimensions [8].

One can also speak of concave symplectic fillings. In the case of strong fillings, one simply requires that the vector field \( X \) satisfying \( L_X\omega=\omega \) (a so-called Liouville vector field) now point into the symplectic manifold along the boundary; in the case of weak fillings, one modifies the definition by asking the contact structure on the boundary to induce the negative boundary orientation.

Concave fillings are much more abundant than convex fillings. For instance, any 3-dimensional contact manifold, be it tight or overtwisted, has infinitely many concave strong symplectic fillings [e15], [e16].

A convex and a concave strong filling of the same contact manifold can be glued along the boundary to form a closed symplectic manifold; the essential point here is that the Liouville vector field provides symplectic collar neighbourhoods. In the weak case, this is far from clear, and so the following result of Eliashberg and, independently, Etnyre about symplectic caps was a major breakthrough, especially given its topological ramifications which I shall discuss below.

To prove this, one may first attach symplectic handles to the weak filling \( (W_0,\omega_0) \) of a given contact manifold \( (M,\xi) \) so as to get a weak filling \( (W_1,\omega_1) \) of a homology sphere \( \Sigma^3 \), with \( W_1 \) containing \( (M,\xi) \) as a separating hypersurface. Now \( \omega_1 \) is exact in a neighbourhood of \( \partial W_1=\Sigma^3 \), and one can explicitly write down a symplectic form on \( [0,1]\times\Sigma^3 \) that can be attached as a collar to \( W_1 \), and such that the new symplectic manifold \( (W_2,\omega_2) \) is a strong filling of the contact structure on \( \{1\}\times\Sigma^3 \). Finally, one may appeal to [e15], [e16] for capping off this strong filling.

3.3. Property P for knots

Here is the promised topological application of Theorem 3.2. For further details, including an extended sketch proof of that theorem, see [e21].

A knot \( K\subset S^3 \) is said to have property P if every nontrivial Dehn surgery along \( K \) yields a 3-manifold that is not simply connected. Recall that Dehn surgery along a knot \( K \) means that we cut out a tubular neighbourhood \( \nu K \) of \( K \), which is a copy of a solid torus \( S^1\times D^2 \), and reglue this solid torus using some diffeomorphism of the boundary 2-torus.

A classical theorem of Lickorish and, independently, Wallace says that every closed, orientable 3-manifold can be obtained via a finite number of Dehn surgeries on \( S^3 \). So, prior to Perelman’s resolution of the Poincaré conjecture, it was a viable question whether one might be able to produce a counterexample by a single surgery on \( S^3 \). A knot with property P is one that does not yield potential counterexamples.

The unknot does not have property P (try this as an exercise, or see [e21], but Dehn surgeries along the unknot only yield \( S^3 \) or lens spaces. The following, however, is a deep and very difficult result [e19].

One important topological consequence is that two knots \( K,K^{\prime} \) in \( S^3 \) with diffeomorphic complements are equivalent, i.e., there is a diffeomorphism of \( S^3 \) sending \( K \) to \( K^{\prime} \). This had been proved earlier by Gordon–Luecke, based on their result that nontrivial Dehn surgery along a nontrivial knot never yields \( S^3 \) (which in turn now also follows from Theorem 3.3). Where, you ask, does Theorem 3.2 enter the proof by Kronheimer and Mrowka? Very roughly, the idea is as follows. Assuming that \( K\subset S^3 \) were a nontrivial knot that does not have property P, we could construct a simply connected 3-manifold \( M_K \) by a suitable Dehn surgery along \( K \). One would then find a symplectic 4-manifold \( W \) of the form \( [-1,1]\times M_K^{\prime} \) with weakly convex boundaries \( \{\pm 1\}\times M_K^{\prime} \); here \( M_K^{\prime} \) is closely related to \( M_K \), but not the same 3-manifold. All that matters is that from \( M_K \) being simply connected one can deduce gauge-theoretic information about \( M_K^{\prime} \) (specifically, the vanishing of its Fukaya–Floer homology).

Now, thanks to Theorem 3.2, \( W \) can be capped off to a closed symplectic 4-manifold \( V \). The Seiberg–Witten invariants and the Donaldson invariants of this purported symplectic manifold \( V \), however, would have contradictory properties. So \( K \) cannot have existed in the first place.

4. Filling of “holes” in contact manifolds

The final result of Eliashberg’s that I want to highlight in this tribute was obtained in collaboration with Helmut Hofer and describes a topological application of Reeb dynamics. Given a contact form \( \alpha \) on a 3-manifold \( M \), the 2-form \( \mathrm{d}\alpha \) is nowhere zero, and so by the linear algebra of skew-symmetric forms, the kernel of this 2-form defines a line field on \( M \). By the contact condition \( \alpha\wedge \mathrm{d}\alpha > 0 \), the 1-form \( \alpha \) is nontrivial on this line field, hence a unique vector field \( R=R_{\alpha} \), called the Reeb vector field of \( \alpha \), is determined by the conditions \( i_R\mathrm{d}\alpha=0 \) and \( \alpha(R)=1 \).

In his ground-breaking paper [e10], Hofer pioneered the use of holomorphic discs in symplectisations \( \bigl(\mathbb{R}\times M,\omega=\mathrm{d}(\mathrm{e}^t\alpha)\bigr) \) for the study of Reeb dynamics, in particular, the existence of periodic Reeb orbits. The existence of such periodic orbits on any closed contact manifold is known as the Weinstein conjecture, and in [e10] this was settled for \( M=S^3 \) and, on any 3-manifold, for all contact forms defining an overtwisted contact structure; see also [e14]. Typically, one starts with a local Bishop family of holomorphic discs (in the overtwisted situation this comes from an elliptic point on an overtwisted disc), and then shows that if the gradient blows up as one tries to extend this local family, this forces the existence of holomorphic planes in the symplectisation \( \mathbb{R}\times M \) whose projection to \( M \) is asymptotic to a periodic Reeb orbit.

In [6], this circle of ideas was used by Eliashberg and Hofer to give a Reeb dynamical characterisation of the 3-ball. Consider the cylinder \[ Z=\bigl\{x^2+y^2\leq 1\bigr\}\subset\mathbb{R}^3, \] with the standard contact form \( \mathrm{d} z +x\,\mathrm{d} y \). Now cut out the 3-ball \( D^3 \) of radius 1 and replace it by any compact 3-manifold \( M \) with boundary \( S^2 \) and a contact form that looks like the standard one near \( S^2\subset\mathbb{R}^3 \). Write \( (\widetilde{M},\tilde{\alpha}) \) for the contact manifold obtained by this cutting and gluing.

One then studies \( J \)-holomorphic discs in the symplectisation of \( \widetilde{M} \) whose boundary circles lie on \( \partial Z\subset\{0\}\times\widetilde{M} \). Here one works with a tame almost complex structure \( J \) that leaves \( \ker\tilde{\alpha} \) invariant and satisfies \( J(\partial_t)=R_{\tilde{\alpha}} \). Away from the ball where \( Z \) has been modified, we may take the almost complex structure corresponding to the holomorphic coordinates \( x+\mathrm{i} y \), \( t+\mathrm{i} z \), so that the flat unit discs in the \( xy \)-plane belong to this moduli space of \( J \)-holomorphic discs.

As one tries to extend this family of flat discs over the region where the ball has been replaced by \( M \), there are now two possibilities: Either the gradient blows up, which implies the existence of quantifiably short periodic Reeb orbits, or the family of discs extends nicely and projects to a foliation of \( \widetilde{M} \), forcing \( M \) to be a ball. In other words, the absence of periodic orbits gives strong topological information. For an extension of this result to higher dimensions, see [e26].

Here is a consequence of these arguments that is a little easier to state, and which can be read as a global Darboux theorem.

In particular, the Reeb vector field of this contact form is diffeomorphic to the Reeb vector field \( \partial_z \) of the standard form, so all Reeb orbits are unbounded in forward and backward time.

Conceptually, what lies behind this statement is that in the absence of

periodic Reeb orbits, one obtains a foliation of the cylinder \( Z \)

(containing the unit ball inside which the contact form has been modified)

by discs given as projections of holomorphic discs in the

symplectisation, and the Reeb flow has to be transverse to those

discs. So there cannot be any trapped Reeb orbits, i.e., orbits bounded in

forward or backward time. As this foliation argument indicates, this

might be a 3-dimensional phenomenon, and indeed it was shown in

[e24]

that on \( \mathbb{R}^{2n+1} \), \( n\geq 2 \), there are contact forms, standard outside

a compact set, that do contain trapped Reeb orbits, even though

there are no periodic ones.

Acknowledgements

Hansjörg Geiges received his Ph.D. in 1992 from Cambridge University. After two years as Szegő Assistant Professor at Stanford University and an assistant professorship at ETH Zürich, in 1998 he took up a chair at Leiden University. In 2002 he moved to his current position at the University of Cologne.