by Donald J. Albers and Constance Reid

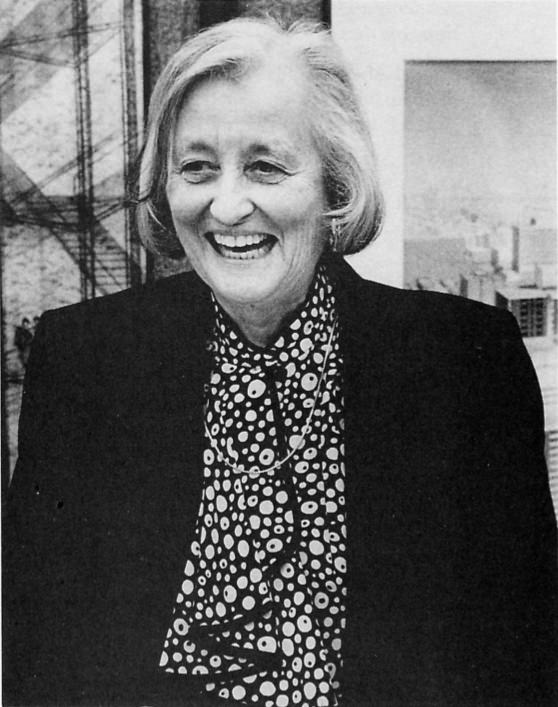

Cathleen Morawetz, a mathematician’s daughter, specializes in the applications of partial differential equations. She is the only woman who has been invited to deliver the Gibbs Lecture of the American Mathematical Society,1 which is traditionally on an applied subject. (She talked on “The mathematical approach to the sonic barrier.”) In addition to her research and teaching, she has been director of NYU’s Courant Institute, a trustee of Princeton University and a director of the NCR Corporation. She says she favors a “new plan of life” for women, according to which they would have their children in their late teens and their mothers would bring up the children.

Mathematical People: There are very few women in mathematics, and fewer still who have done the things you have done — even fewer who have a husband of forty years and four children as well! You’re really quite remarkable. We know from your curriculum vitae that you were born in 1923, in Toronto, the daughter of the well-known Irish mathematician, J. L. Synge.

Morawetz: Well, I was born in 1923 and he was born in 1897, so he was only twenty-six. He was not well known then.

MP: So was the position in Toronto his first?

Morawetz: Yes. He had come to Toronto at the invitation of A. T. DeLury, the head of the Mathematics Department, who was of Irish stock and a great fan of J. M. Synge, the playwright — my father’s uncle. I think my father wanted to leave Ireland at that time. He had been a student during the Easter Rebellion of 1916, and although his and my mother’s sympathies were with the Nationalists [the Irish rebelling against British rule], both of their families were divided.

MP: Your mother was also Irish?

Morawetz: Yes. Also born in County Wicklow.

MP: So you are one hundred per cent Irish?

Morawetz: That’s right, but I’m also Anglo-Irish because both my parents were Protestants from the south of Ireland, which is really very different from northern Ireland.

MP: I am interested in the fact that you are the second of three daughters of J. L. Synge. I have read that women scientists are quite frequently second daughters. The explanation given is that a second daughter feels that she should have been a boy, so there’s a tendency for her to take after the father and try to become a son in her interests. I don’t know whether that is true.

Morawetz: I was the boy in the family. I was the boy from the word go. But that doesn’t mean that I had an especially close relationship with my father. My older sister really had a closer relationship. For instance, when we were girls and we wanted to do something he didn’t want us to do, she was always delegated to negotiate with him. I would say rather that I was in competition with my father. Better not print that! [Laughs.] That was the pattern, quite different. But I was definitely the boy. In fact, it was rather funny. When I was seven and we returned to Canada from Ireland, I had had a major operation on my leg so I had my leg in a brace. It had been arranged that my father was going to look after me, and my mother was going to look after my little sister, who was just a baby. My older sister was going to look after herself. It was all very formally arranged. And the first thing my father did was to take me to have my hair cut like a boy’s. This was supposedly because it was a mess and he didn’t want to have to take care of it, but that’s what he did. Of course that was 1930, and that was a time when people did have their hair cropped. But when the people on the ship said I was a little boy, I was very unhappy.

MP: Do you mean that you were a tomboy?

Morawetz: That’s right. I wasn’t very athletic, so I didn’t do sports — but I was the one who played with the Meccano set. Now I do remember having a dispute with my sister about a doll, so I must have been somewhat interested in dolls, too, but in general I liked the Meccano and that sort of thing. I constructed engines and levers. And it’s true I did that with my father.

MP: Did your mother have any mathematical interest?

Morawetz: She went to Trinity College and studied mathematics, but her brother persuaded her that there was no future in math for her, so she switched to history. At one point, when she was ready for secondary school, there was a competition among the Protestant girls in Ireland and she placed first. Actually she won a prize to go to the conservatory of music in London, but her mother wouldn’t let her go. She went to Trinity College instead, and that’s where she and my father met. After they were married — he was still in school then — she taught to support them, so she never got a degree.

MP: Genetically you’re really packed for mathematics!

Morawetz: Yes. I think so.

MP: When you said that you were in competition with your father, to what period of your life were you referring?

Morawetz: Why do I say that? Well, I just think we were in competition. It’s true we had this common interest, that we liked to do these mechanical things. Later we liked to sail. We both enjoyed that very much. But there was always a wee competitiveness there.

MP: Did you think you could make better levers and other mechanical things than your dad?

Morawetz: No. Certainly not. Not at all. I should add that I was very close to my mother. I think that I had a much more intimate relationship with my mother than my sister did. My older sister, I mean. My younger sister was much younger — seven years.

MP: Did you show an early interest in mathematics?

Morawetz: Well, it was clear when I was very small that I was good at school. For example, when my older sister started school at the age of five — we began with my mother teaching us at home, but that didn’t work — I made a terrible fuss. I insisted that I had to go to school too, and so my mother took me down and persuaded the principal — it was a private school — to take me. I started school at the age of three. They kept me in the first year for two years. I was very annoyed about that.

MP: Three years old and in what was ordinarily first grade?

Morawetz: I think it was called kindergarten, but you learned to read. I learned to read at the age of three.

MP: You were really determined to go to school. That’s a good mathematical quality — stubbornness.

Morawetz: Yes. In fact, I had a reputation as a child for being — well, sort of stubborn.

MP: Are you still stubborn?

Morawetz: I’m tough. [Laughs.] My father said to me just the other day, “We’re both tough.”

MP: In the article on you in Science a few years back, you were quoted as saying, “My father’s attitude was that I had talent in mathematics but that I was not willing to work hard enough.”

Morawetz: That was later — when I was an undergraduate at Toronto. I think the earliest I remember my father telling me something mathematical was when I was beginning to study Euclidean geometry at school. At that time he also told me about cartesian geometry. I must have been twelve or thirteen.

MP: And you liked cartesian geometry?

Morawetz: Yes, I liked it, but I didn’t really pursue it. We never had any formal lessons.

MP: So what was it about mathematics that first captured your interest? Was it simply that you were good at it?

Morawetz: Well, I wasn’t good at arithmetic. I used to get bad marks in mental arithmetic. I found that annoying, because I didn’t think it mattered. But I was a good student all around. I thought at one time in high school that I would go into history.

MP: You didn’t concentrate on mathematics?

Morawetz: I concentrated on mathematics in the last year of high school — we had five years of high school in Toronto — because I had a teacher, Mr. Reynolds, who was putting us up for scholarships. These were competitive scholarships. He was a very nice man, and he ran a little class to coach about five students. Looking back, though, I realize that he ran the class for me. He taught me quite a lot. My father wasn’t particularly interested in what I was doing, and I wasn’t interested in discussing it with him. In fact, when we got stuck on our homework and asked him for help, he would write on a piece of paper — he always used only one side for his own work — and then the great object was to get out of his study with the piece of paper because, of course, we were so scared of him that we couldn’t hear what he was telling us at the time, but we hoped that if we had the paper…

MP: Did you go to a public high school?

Morawetz: Yes. The high school system consisted of vocational schools and academic schools. If you wanted to go to the university, you more or less had to go to an academic school, but of the students in the academic school I would say only about ten per cent went on to the university. And, of course, nobody thought of going away to college.

MP: So the scholarships you spoke about were for the University of Toronto?

Morawetz: That’s right. There was a really quite tough exam in all subjects, and after that there was a sort of mathematics problems exam, so the possibility of winning one of the scholarships was much higher if you were good in mathematics. The top ones were all won by mathematics people. I was in a very good year. The person that won the highest prize was Jim Jenkins, who is at Washington University in St. Louis. Robert Steinberg, who’s at UCLA and was just recently elected to the National Academy of Sciences, won one of the other prizes. So I was in a class with Jenkins, Steinberg and Tom Hull, who’s at the University of Toronto — it was quite a group of people. I won one of the prizes too but, emotionally, I cannot forget that I cared most about the fact that there was a top prize which I didn’t get. I was so disappointed that when people congratulated me — there was a whole bunch at the next level down, which were worth a lot more money — I felt like crying.

MP: There are many people who come in second.

Morawetz: It was not the coming in second. It was everyone knowing about it!

MP: So is it correct that when you came to the university as an undergraduate, you did not know that you would go into mathematics?

Morawetz: Oh no. The way it was set up, you entered into a joint course — math, physics and chemistry. The first year you took all three, the second year you took two of the three, the third year you took one, and the fourth year you took half of the subject — in mathematics it was pure or applied mathematics. The undergraduate program in pure mathematics was very tough, and frankly I would say overloaded with courses. I was not prepared to devote myself sufficiently — it was too tough for me — so I ended up in applied mathematics, where the spirit was different.

MP: What was your major called?

Morawetz: It was called M. & P. — Math and Physics. All the Toronto people of my generation and even later know that expression. But it was much more than a major. You took nothing else.

MP: You took no liberal arts courses at all?

Morawetz: Oh well, the University of Toronto had a number of religious colleges and one that wasn’t religious. The religious colleges had one hour a week for “religious knowledge.” Since I was in the nonreligious college, I had one hour a week for something else. One year I took English, one year I took Oriental literature, and one year — oh, philosophy! And that’s all the liberal education that I got.

MP: And with your father’s interest in writing!

Morawetz: My father’s attitude, which came really from his family, was that by the time you finish high school you know how to write — that’s not something you do at the university. You don’t study writing!

MP: So you graduated with a bachelor’s from Toronto?

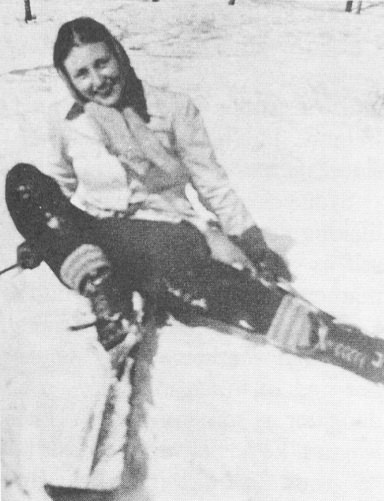

Morawetz: Yes, but before that I had a very important interruption in my life. The second World War had broken out while I was still in high school. Toronto was, of course, a center of strong support for Britain. By the time I was in my third year of the university, half the class had gone off, including a boyfriend of mine. I wanted to do something too. So I decided to do what the boys had done, which was to join the Navy. But, you see, they were immediately made officers while I was told that I would have to take boot training! I was very annoyed, and my great desire to join the Navy suddenly dropped to zero. But I did want to do something, so my father got me a job at the Inspection Board of the United Kingdom and Canada, just outside Quebec City.

MP: So you left college?

Morawetz: At the end of my third year I took a year off. That was the first time I had ever been away from home. It really was a fascinating experience. And that experience came back to me recently when I saw a reference to Malcolm McPhail in the biography of Turing. McPhail was my boss. I was supposed to be a scientific assistant of some kind to him, but he had very little for me to do and I found the job very boring. I was much more interested in the life that was going on around me. So I asked for a job as what was called “a chronograph girl.” This was something that I was supposed to be much too educated for, and I was, so that was a mistake; nevertheless, looking back, I realize that I was operating a very early digital computer. There were several of us. Because our work was boring, we used to play games with the machine. I realize now that standard deviations must have mattered, so the errors we produced by playing games must have been enough to throw off the results. It was disgraceful, but it wasn’t really our fault. We were not properly supervised. However, it’s also true that McPhail awoke my scientific interest. You see, when it rained you couldn’t measure shells with this thing because it depended on an electric eye. So there was an older machine — I remember its name, a Boulange Machine — with which you could measure velocity with a dropped rod or some such thing — and there was a scale etched on a piece of steel from which you had to read off what the speed was. Well, I discovered that the scale was wrong. It was not wrong by a great deal, but it was wrong. So I did some experiments and checked the theory and wrote a little note. That was the first time I thought, “Well, science is fun.”

MP: It hadn’t really been much fun up to then?

Morawetz: It had not been fun at all. I had this big scholarship, and I worried every year whether I would keep on having it. It wasn’t fun. It was school. And that was terrible, because I had some great lecturers. I had Coxeter and I had Brauer and I had my father. That’s, of course, another story — having your father. I also had Alexander Weinstein and Leopold Infeld. Now Infeld was not wasted on me. Infeld was a terrific lecturer. He lectured without notes, he really mostly just talked, and he rarely put anything on the blackboard. Once, though, he was talking about Green’s theorem, and he wanted quite rightly to stress its importance, so at the proper moment he opened his jacket, pulled out a piece of paper, and copied from it in very large letters the formula for Green’s theorem and the limiting process. I can still see it on the blackboard! I have never forgotten it.

MP: What kind of teacher was your father?

Morawetz: My father was tremendously well prepared. His lecture notes were terrific. Of course he was — basically is — a shy person, and he didn’t know how to treat me in class. This is a story I often tell. He couldn’t remember names, so he had the arrangement that three students would sit in the front row and he would ask them the questions. Well, eventually, as you work your way through the alphabet, you come to Synge. I remember that I was in the middle, and he came to me and he looked at the name, paused, and finally said — “Miss Synge!” Of course that brought down the house. But he was always very correct. For example, every year when the faculty met to decide on honors, he absented himself if I was involved.

MP: So after your wartime job you came back for your final year at Toronto?

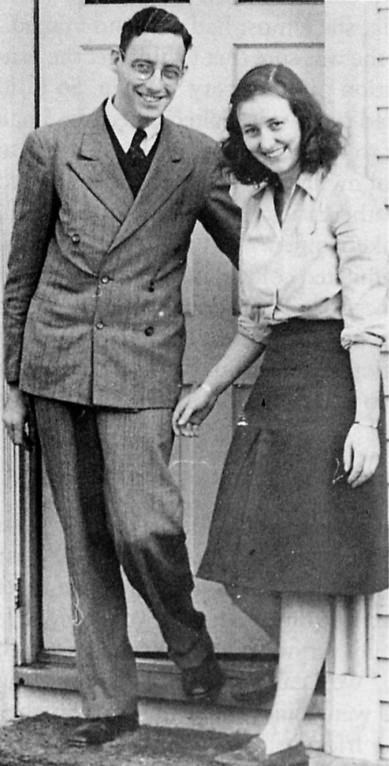

Morawetz: That’s right. My father was gone by then. I was no longer with that jazzy class. I was the best student now. And that’s always very good for the ego. Competition is bad for me. It just throws me right down, down and out. And so I was much happier. I lived in a dorm, which was an experience I really liked. I also met Herbert Morawetz early that year. Altogether it was just a change, a wonderful change, and I really enjoyed myself.

MP: When you then went down to MIT, were you following Herbert there?

Morawetz: No. What happened was that I wanted to do something exotic. I had found it very interesting to go and live in Quebec. It was a different culture. So I wanted to do something else exciting. I saw an ad for teachers in India, and I decided that I would go to India. And then a person I should really have mentioned long before, Cecilia Krieger, a mathematician on the faculty whom I had known from childhood, asked me what I was going to do. When I told her about India, she almost had a fit and immediately declared that if I would only apply she was sure that I could get the Junior Fellowship of the Canadian Association of University Women. So I did apply, and I did get it. The place I wanted to go was Caltech, because I had decided by then that I really didn’t want to be a mathematician, I wanted to be an engineer — which was the reverse of my father, who went to college to study engineering and decided to do mathematics. So I applied to Caltech, and they wrote back that they didn’t take women. And that was that. My father by that time was serving as an assimilated colonel in the American Air Force, and he was essentially incommunicado in Paris, doing ballistics tables for napalm bombs, it turned out. So I consulted Infeld, and he suggested MIT. They took me and gave me a tuition scholarship. Herbert was much relieved. He had thought that if I went to California that would be the end of us.

MP: Tell us a little about Herbert.

Morawetz: Herbert had come to Canada in 1939 as a refugee from Czechoslovakia. He had finished chemical engineering at Toronto the year that I went down to Quebec; he had then got a master’s degree. When I met him he had his first job. He had had a terrible time getting it, you know. He had been the best student in his class, but everywhere he went he was told, “We don’t hire Jews.” Some people said, “We’ll call you back,” or something like that, but half the people at least were quite open about why they wouldn’t hire him. In the end, through a friend of his father’s, he got a job with the Bakelite Company in Toronto, but those people really didn’t want to have him either. We had become engaged during the summer I left for MIT, and while I was gone he arranged to be transferred to Bound Brook, New Jersey. I finished at MIT with a master’s degree. Neither of us intended at that time to go on and get a Ph.D.

MP: Was your master’s in engineering?

Morawetz: No. The first term I was at MIT I took a lot of electrical engineering, and I discovered two things. One was that my arithmetic was still no better than it had been, and it really mattered. The other was that I was no good at experiments. So I went back to applied math and wrote a master’s thesis with Eric Reissner. By that time I was married — I got married in the middle of the MIT thing. I was the first commuting wife. Everybody thought I was crazy to commute, and everybody thought Herbert was crazy to let me.

MP: Did you know when you married Herbert that he was a basically liberated man?

Morawetz: Oh yes, he assured me that he would not interfere with my career. Did I really know? I don’t know. I only believed what he said.

MP: Did he also come from an academic family?

Morawetz: No. When his father left Czechoslovakia, he was the president of the jute cartel and owned a big factory.

MP: Did his mother have a profession?

Morawetz: No, no. They were very wealthy Jewish bourgeoisie, too wealthy for the woman to have a profession. In fact, Herbert’s mother had never gone to college, although she was essentially the same generation as my mother. It’s not even clear that they would have sent their daughter to college in Czechoslovakia, although she like Herbert is very intellectual. She did go to college in Canada and is a writer. Even as refugees, the Morawetzes were very well off by my standards, although not by theirs. Certainly the notion that to be a good mother you have to wash the diapers was absolutely foreign to all of them. My mother-in-law, however, did have some reservations about women working outside the home.

MP: But you wanted to work?

Morawetz: Well, after I got my master’s degree, I looked for a job in New Jersey. I applied to Bell Labs, and they told me that although I had a master’s degree from MIT they would not let me into their general program for master’s degree students. I felt that a bachelor’s degree from Toronto was also worth a lot, but they didn’t understand that either. I was to be pooled with the other women bachelors who could have got their degrees anywhere, you know. I was furious. I said, “I’m not interested in that!” Unfortunately I’ve never kept any records. It was probably on the telephone anyway. Then — it must have been at the summer meeting — no, at the Christmas meeting of the American Mathematical Society — my father met Richard Courant. Gertrude Courant had just gotten married, too, and my father and Courant were bemoaning the fact that their intellectual daughters were not going to be able to pursue their careers and so on. Now my father denies this story, but the fact is that this is what he told me at the time — Courant said, “You can’t do anything for my daughter, but perhaps I can do something for yours.” I was to come down and see him at NYU. So I came down, and that’s when I had the interview with Courant that figured in the MAA movie about him. I remember he said, “Well, I really need some reference besides your father,” so I gave him the name of Alexander Weinstein, not knowing that the two men disliked each other intensely. So that’s how I came to the Institute at NYU. Courant had hired me to solder connections on a machine that Harold Grad was making to solve linear equations. The job involved my commuting an hour and a quarter from New Jersey, and that was a major obstacle. The other obstacle was that Harold Grad immediately ran out and hired somebody else to do the soldering.

MP: Because you were a woman?

Morawetz: He told me many years later — and I thought it was very nice of him to do so — that that was really how it was. So when I arrived there was no job for me. From time to time Courant would mumble, “Well, can you write English?” and I would say, “Yes.” Finally he gave me the job of editing the Courant–Friedrichs book on shock waves.

I started at NYU in March or April. At that point I had no intention of going to graduate school. I didn’t consider myself a student. But by the time September rolled around — that was ’46 — Courant’s group had shed a lot of its military work and everybody was going back to purer mathematics. Friedrichs was planning to teach topology. That was a big thing, you know. Faculty members as well as students were going to take the course. So I decided to take it too. It was very exciting, and it was very competitive, but it was a much gentler kind of competition than what I had known before, although it’s true I cried when I couldn’t do the homework.

MP: So there you were at what was not yet known as the Courant Institute, hired by Courant to solder connections but given the job of editing a book by him and Friedrichs. That was a pretty tough book. You must have exuded a certain amount of confidence.

Morawetz: Oh no, I didn’t at all. I was so shy that when I arrived at the Institute I would literally make a run for my office.

MP: But you spoke English, and you came from a cultured English-speaking family.

Morawetz: Yes. That was important. But there was also another thing. Courant had been having trouble with the people he’d been getting to help him with his books. Of course, there had been the mess with Herbert Robbins over What Is Mathematics? Then my predecessor on the shock wave book had been Jimmy Savage, and among other things Savage hadn’t liked the first chapter — there hadn’t been enough about entropy in it, you know. Well, my attitude was that what went into the book was what Courant and Friedrichs wanted to have in the book. If they wanted to take out all that stuff about entropy, I didn’t care. I was just fixing up the English and making sure the formulas were right. And I think that was what they really wanted. The other editors had been much too eager to do another kind of editing job.

MP: Still, it must have been a tough book to edit.

Morawetz: The funny thing is that when it came out, many people said, “Well, this is nothing like his other books or their other books,” but the truth of the matter is that it has really held up. Just yesterday I met an engineer, a Ph.D. in aeronautical engineering, who told me that it’s still the bible among engineers. I knew that it is still the bible in the theory of compressible fluid dynamics, but it was interesting to hear that it’s still the bible in the engineering business. After all, it’s pretty old. There are a whole lot of later books on the subject that are already totally out of date. But it’s held up.

MP: One thing that has always surprised me is the rather casual way in which Courant took a number of women into the Institute, very much as he took you in.

Morawetz: I should say about that — Courant was wonderful to me, although he could be not so nice to me too. But I got on my feet by going there. After I had been there a year, I went in and told him that I was pregnant. He says, “Oh my god!” and he rushes off. Then he comes back and says, “You’re taking your orals next week.” It was his idea that if you had taken your orals, you could always come back and do your dissertation; but if you hadn’t, you probably wouldn’t come back. I immediately went to Donald Flanders, who I knew would understand, and said, “I can’t do that. You would just be giving it to me. I couldn’t stand that.” So I took my orals after my daughter, Pegeen, was born.

MP: Just for the record, what are the years of your children’s births?

Morawetz: ’47, ’49, ’52, and ’54. I got my Ph.D. in 1951.

MP: Can you give our readers some tips about being a mathematician and a mother?

Morawetz: Well, I got the tips from Mildred Cohn, the wife of Henry Primakoff, a physicist who had worked at the Institute in New York. They were also on a visiting thing when we were in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1950–51, and we saw them fairly often. She was older than I, a very successful biochemist with several children. She obviously knew how to handle it all. She emphasized having help and the importance of paying for the help. Now, looking back, I think I should have paid more and tried to have more continuity. The best help I had was au pair people, but they stayed only a year or so. I think now that it was a little hard on the kids not to have a mother-substitute.

MP: From time to time I have asked women in mathematics how they happened to choose their particular field, and my sample survey shows that most of them are in very pure fields which are clean and ladylike. But the titles of the papers here in your bibliography strike me as representing so-called “masculine” interests.

Morawetz: Well, Mony Donsker always used to get a rise out of me by asking how come I was working in magneto hydrodynamics — that wasn’t very feminine. The truth of the matter is that most women — in fact, most people — don’t have the broad education that I got in Toronto. I learned a lot of physics. I took circuit theory as an undergraduate and a little bit of elasticity and optics. The applied mathematics at Toronto was very close to physics. Some of it was taught by engineers. Now it’s also true that I was taking algebra with Brauer and geometry with Coxeter, and both subjects fell on deaf ears. I never got really interested in, and don’t think I would be very good at, all those structure problems that occur in pure mathematics. I can still remember listening to Brauer defining fields and rings and thinking what was it all good for. On the other hand, I was very pleased when I once proved something for Friedrichs that was not applied at all!

MP: Why did you do your thesis with Friedrichs rather than with Courant?

Morawetz: Well, I’ll tell you what comes immediately to my mind. I’m not sure though that I really think it’s true. But it was because I thought it would be tougher. I constantly worried about being handed things on a platter. I felt that if I did a thesis with Courant he would just give it to me. Friedrichs wouldn’t do something like that. So that was a very important thing for me. But actually what happened was this. I was between children. After I passed my orals, I went in to see Friedrichs. At that time he had stopped being interested in fluid dynamics and was tremendously involved in quantum mechanics. He put all these problems on the board and talked about various things and kept saying, “You know, you just have to be really eager and enthusiastic.” And I couldn’t get enthusiastic about any of them — I was back to square one. I started working on something — I’ve forgotten now what it was — but at the same time, you see, I was earning my stipend by working on a problem for the project that was applied — or more applied — in fluid dynamics. I had had a miscarriage after my first child and I was pregnant with my second, so I must have been a little bit in and out of it. Anyway, when I told Friedrichs that I was pregnant, the gods at the Institute arranged that my project work would be turned into my thesis. That was fine, but then after I had the child — that was John — and came back to the thesis, which involved an interesting problem in asymptotics in ordinary differential equations that Langer’s theory didn’t cover, I wasn’t able to prove the theorem. And that, I found, was very depressing. I did some computations that partially verified the conjecture, but I was never happy with the work and never published it. Actually it was on the theory of implosions, and I did not know when I worked on the problem that an implosion was what made the atomic bomb go off. I learned that — rather Herbert told me that — when it came out in the trial of the Rosenbergs.

MP: How did you find working with Friedrichs?

Morawetz: Well, he was a little difficult at that time. He was so interested in quantum mechanics that he didn’t want to think about what I was doing in fluid dynamics. Now, since I’ve had students of my own, I know how he felt. I had the office next to his, but I had to make an appointment if I wanted to see him. He was a very regulated person, you know.

MP: So when did you finally get really excited about mathematics? You don’t crank out papers like these [indicating her bibliography] in a state of boredom.

Morawetz: Well, don’t forget, juggling kids and so on has a dissipating effect on one’s enthusiasm. But when I went back to MIT in 1950–51, I found the way C. C. Lin looked after me really terrific. He was organized but organized on a different pattern from Friedrichs. He would give me a problem and if I hadn’t made any progress in five weeks, he would take it away and give me another one. I was at MIT a year, and after a couple of months I really latched onto something. It was again ordinary differential equations, but one of the things that helped was — you see, I hadn’t been able to do the case in my thesis but these cases I could do. Also there were very interesting applied mathematical reasons for doing them. So I became quite interested. When I came back to NYU, I was again floundering. Then it was Lipman Bers who gave me a paper to read on mixed equations and — did I find a mistake in it? or make an improvement? I think it was an improvement. So then I got going on that.

MP: That must have bolstered your self-confidence.

Morawetz: In mathematics there is frequently the problem of kicking up one’s enthusiasm. Another time when I really didn’t know what to work on and was struggling with a paper somebody had given me about singular ordinary differential equations with some pathological behavior, Jürgen Moser came by and said, “Ach, it’s ridiculous to work on that problem.” So I threw the paper away. What got me working on the wave equation, which later dominated a lot of my work, was a lecture by Joe Keller on unsolved problems. As I was sitting there, I saw that the technique I had used on mixed equations ought to have applications to Keller’s problems — they were elliptic this way and hyperbolic that way — and that really worked out. I don’t believe that I ever again had the feeling of absolutely floundering.

MP: Don’t you think also that for you, as for most women, the problem of having children and getting them going is not only an absorbing but a necessarily absorbing problem?

Morawetz: Oh yes. Even just having the children, being pregnant and giving birth. There I was very lucky. I had an easy time. I felt better when I was pregnant and I did better work. And the births themselves were not a problem.

MP: Once you were at NYU, embedded in a pretty heady atmosphere, you certainly didn’t want to be just an average NYU professor. You don’t like being average.

Morawetz: That’s right. Sometimes when I’m asked about my career, I say, “Look, I was such a lousy housekeeper — I was a failure at that — so I had to do a good job at something!” Sure, there was an element of that in it, you know. That’s often a factor in a woman having a career. But there’s one thing that you mustn’t forget — that I think is very important. I came from an atmosphere where there was a sense that a woman should have a career — my mother was interested in that — but all that had somehow disappeared after the men came back from the second World War.

MP: That was the era of four children and a station wagon.

Morawetz: That’s right. And then came the sixties when everybody suddenly rediscovered this career thing. But I had never lost track of it. That is one thing I should say. The other thing is that until the women’s movement of the late sixties it really was considered very bad form for a woman to be overtly ambitious, very bad form. Everybody thought that way — my colleagues, Herbert. It was fine for me to have a career, but not actually to show my ambition. Although it was positive to say that a man was ambitious, you could never say it about a woman — except negatively. And I think of course that underneath I was always very ambitious.

MP: I never have had the impression, you know, that you were out after these jobs that you have got — director of the Courant Institute and so on. Whether you cultivated it consciously or subconsciously, or whether it was just your nature, you did not pose a threat to the men here.

Morawetz: I don’t think that I was really “out after these jobs” or that I posed any mathematical threat — well, I guess [laughs] that there are some of my colleagues for whom I must have posed a mathematical threat — I was looking up instead of looking down.

MP: Did it seem to you an unusually long time until you became a professor?

Morawetz: Oh yes! I was annoyed about that. It took a little longer than it should have. Of course it is also true that in a way I always worked part-time. I was paid four-fifths salary for many years. Herbert always said, “That’s fraud. You work more than full-time.” But I felt much better that way. No one could question, as they had at MIT, whether I was really earning what I was being paid. So that arrangement could have accounted for the delay in the appointment.

MP: How did your administrative involvement at the Institute develop?

Morawetz: It came about as a way to keep the teaching down. I used to be a very nervous and unhappy teacher, and I spent an awful lot of time preparing my lectures. If you taught in the Institute, you taught only graduate courses, so a full load was two graduate courses. I just found that a big burden. Let me see — oh, I know how it first came about. Fritz John became the director of a division, and Courant worried that Fritz didn’t really want the job and it would be a burden on him, so I was made his assistant and I did the job and got in return a reduced teaching load.

MP: It seems to me that women often have a way of taking care of a department. I don’t mean just seeing to the coffee. They notice things.

Morawetz: That’s true. In fact, I’ve had young women complain that they were made the chairman of the department — it wasn’t a job they really I wanted — while they were still associate professors, or probably even assistant professors.

MP: You seem to have thrived on administration.

Morawetz: It certainly suits me. I like to do it.

MP: What is it that you like about administration?

Morawetz: I like the relationship with human beings. Many, many years ago one of the things that made me not want to go into mathematics was the fact that it seemed to me a very lonely life.

MP: You saw this in your father?

Morawetz: I saw it in my father, and [laughs] my children saw it in me.

MP: Did you ever think seriously about leaving NYU?

Morawetz: There wasn’t any possibility of leaving. Where could I go? Most places would not have hired me. So I never gave leaving serious thought.

MP: It has always seemed to me that the Courant Institute is more people-oriented than most mathematics departments.

Morawetz: That’s really true. There’s no question about that.

MP: When was it that you started branching out into the many different organizations in which you are now so active?

Morawetz: Well, I got involved in the American Mathematical Society in the late sixties when I went to a trustees’ meeting in New York to ask them to form a committee on women. I did not want the Association for Women in Mathematics to speak for all women mathematicians. I joined them later, but at that time they were terrible attackers. They even attacked Lipman Bers in the early days, and Bers was the best thing that ever happened to women in mathematics!

MP: They later honored him.

Morawetz: They honored him, but that was quite a bit later. They even attacked Olga Taussky. It was unbelievable. So I was on a committee for disadvantaged groups in the Math Society, and I thought there should be a separate committee for women. I was terribly afraid when I went before the Board of Trustees — or it may have been the Council. Anyway, when it came my turn to speak, I said, “There’s a problem with women. You may have noticed that there are not many women mathematicians.” At that point Saunders Mac Lane said, “Well, mathematics is a very difficult subject.” I was not up to coping with that, but Iz Singer picked up the ball. The committee was formed and I was made chairman. That’s how I got involved in the Math Society’s affairs. I hardly ever even went to meetings when I was young.

MP: What do you think are the biggest problems confronting women in mathematics today?

Morawetz: Well, as one of my colleagues has pointed out, “Mathematicians don’t look very far for their wives.” The result is that they’re usually fellow graduate students. Women mathematicians tend to be married to men mathematicians, and so they need to find two math jobs in the same geographical area. That’s very hard. Then I would say that, in spite of the fact that men are — and they really are — much more helpful and supportive these days, the burden of raising children still falls on the woman — at a time that’s very important in her career — just about when she should be getting tenure. In fact, I’m about to institute a new plan of life, according to which women would have their children in their late teens and their mothers would bring them up. I don’t mean the mother would give up her career, but she’s already established, so she can afford to take time off to look after the children. Besides, I love being a grandmother!

MP: You’re not particularly optimistic about change?

Morawetz: No. I’m not at all optimistic. I think there has been a big change, but I’m not sure what would really make a turnaround. Take this business of raising kids. It’s very difficult. Somebody has to be in charge. So it’s got to be either the mother or the father. As things are set up now, it’s the mother. I see it with my daughters — they are the ones who are in charge of the children. It’s very nice in a way, but it’s also a handicap professionally.

MP: Do you think that, career-wise, women naturally operate on a different time-scale from men?

Morawetz: I think that there is something to that idea. Whether it has to do with the environment or circumstances of adolescence I don’t know. But I’ve rarely seen — no, I will say I have never seen an adolescent girl who’s like, say, Gene Trubowitz age 19 or Samuel Weinberger age 18, whose whole lives are embedded in mathematics. They really live for that and that alone. I’ve never run across girls like that. But I am sure they will appear. To a large extent it is a problem of time-scale. All career patterns in science and in everything, in fact, are set up on the basis of the male. They ought to be somewhat different for women, but until there are enough women involved, that won’t happen.

MP: What advice do you give to young women who are coming to like mathematics and to show real talent?

Morawetz: Well, there is a big difference between those who want to have a family and those who don’t.

MP: But often you don’t know you want a family until after you have had one.

Morawetz: That’s very true. So you have to expect the guy to make some sacrifices, more sacrifices. That’s really what it amounts to. And I think that the major sacrifice is in his standard of living. But, you see, one of the main problems is that there are so few marrying men and it’s still the old thing, you know — you have to spoil them a bit to get them!

MP: Well, there are not too many marrying men, and among those there are probably not too many so-called liberated men.

Morawetz: Even if they are theoretically liberated, there is also the difficult thing for men, which is that under those circumstances they usually end up being bossed around. That’s a difficult situation for anybody to be in.

MP: Did any of your daughters ever show an interest in mathematics?

Morawetz: Well, the second one, Lida, who is a psychiatrist, is definitely very gifted scientifically. Mike Artin tried to talk her into staying in mathematics, but she said that if she were to be a mathematician she would want to be a pure mathematician and she couldn’t see spending her life doing anything so unuseful — furthermore, life would be too lonely. Now she sees that being a psychiatrist is a much more lonely life. I believe to some extent that she was a casualty of the anti-science attitude of the late sixties. With me my father had the attitude, well, if I wanted to do mathematics, that was fine; but he was very disappointed when she didn’t go into mathematics.

MP: I saw in the paper recently that you just collected an honorary degree from Princeton.

Morawetz: I’m glad you brought that up because one of the things that you haven’t touched on is Princeton, which was really a very important change in my life. When my youngest daughter, Nancy, was an undergraduate there, they had just gone co-ed. They had two women trustees who were both daughters and wives of Princeton graduates, and someone — I think it was McGeorge Bundy — came up with the idea that they should now look for a professional woman who had a daughter at Princeton. President Bowen called me for an interview. I had no idea why, but Herbert said, “They’re going to make you a trustee.” I said, “How can you ever imagine that?” But, sure enough, that’s what they did. It was very interesting for me. Princeton is so very different from New York University! There is no financial struggle for modest endeavors — they have a very generous endowment. Of course they also husband their resources very carefully. That was impressive to me. Another thing that impressed me enormously was that they were so gracious, even when they disagreed. I was made vice-chairman of the curriculum committee. Then Mike Blumenthal, who was chairman, was made Secretary of the Treasury and I became chairman. The experience at Princeton led to other things. Without it I doubt if I would ever have been chosen as a director of NCR or as a trustee of the Sloan Foundation.

MP: So Princeton opened up non-scientific things, all of which you enjoy?

Morawetz: That’s right, although I worry about some of them too, you know. I realize that decisions have to be made on relatively little information. I guess all administrators have that problem. I have that problem now, too. But getting out into the world was important for me because I had grown up in this cocoon at the Institute. The cocoon was nice and wonderful and fun, but it was good for me to get out.

MP: Well, you’ve certainly done a lot of exciting things, had a lot of firsts, a lot of honors. I know that you’re not inclined to line them up and rank them, but what have you felt especially proud of?

Morawetz: I can’t really answer about being proud of something.

MP: Well, let’s not use the word proud. What has given you the most pleasure?

Morawetz: Ah, there’s no excitement to beat the excitement of proving a theorem! [Laughing.] Until you find out the next day that it’s wrong. It’s funny that I should think of it now, but I remember when I had proved the thing about decay that Joe Keller had put up as an unsolved problem and Clifford Gardner said, “You know, there are some things that get printed. They make long and important papers. But there are other things that just simply go into textbooks.” I don’t know that mine made it into a textbook, but that was one of the nicest compliments I have ever had. I’ll tell you, though, there is something about being a mathematician that is extremely difficult. One of my children put it this way: It’s that you’re on stage all the time. You can’t fake or shift the subject of conversation and so on. That’s very demanding of people.

MP: But you like that.

Morawetz: I guess that in a way I do, although at times it’s also depressing.

MP: You never wanted it on a platter. You told us that.

Morawetz: Well, that was when I was rather puritanical about such things. Now I’d be willing to take the platter!

MP: I certainly think you can be satisfied with your life.

Morawetz: Well, I am, I really am. You know, when I was eighteen or nineteen, before I went down to Quebec, I was very depressed. I probably should have been seeing a shrink. But the fact is that as everything has gone — with all these “pleasures” of success and so on — I really never come close to feeling acutely depressed anymore. I think that maybe doing all the things I do is a protection, because many mathematicians do get depressed when they can’t solve a problem they want to solve.

Addendum by C.S.M.

In reading this interview over, I find that I may have emphasized the need to escape from the devils of mathematics to embark on the pleasures of the real world. But it works both ways, and sometimes the devils of the real world drive one into the pleasures of studying mathematics.

June 1986 in South San Francisco, California.